Scientist of the Day - Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Pauli, a German physicist, was born Apr. 25, 1900. Pauli came of age during the heady times when Albert Einstein had just advanced general relativity and Arnold Sommerfeld and Max Born were working out the details of a quantum theory of the atom. In 1925, Pauli proposed that the energy level of electrons in an atom is determined by a set of four quantum numbers, such as orbit radius and angular momentum, and that only one electron in an atom can have a particular set of those four numbers. This restriction came to be called the Pauli Exclusion Principle, and it explained why all the electrons in an atom do not drop to the lowest energy level. To put it another way, it explains why we don’t instantly collapse into a small heap of tiny sub-atomic particles.

One of the quantum numbers was new with Pauli, and it came to be called “spin,” so in a sense, Pauli was the discoverer of electron spin. He was also the first to propose the existence of neutrinos, nearly massless neutral particles that are emitted during beta decay. They were postulated by Pauli to ensure that energy was conserved in such interactions. He actually wanted to call these neutrons, but when that word was used in 1932 for a much different kind of neutral particle that shares the nucleus with protons, Enrico Fermi saved the day by renaming Pauli’s little neutral particle the “neutrino,” which means, in fact, little neutral particle, in Italian. Neutrinos would not be detected until 1956.

Pauli was also renowned for being fatally dangerous to experimental apparatus – if he came into a lab, it was said that all the equipment would immediately quit working. This was known as the “Pauli effect.” A group in Germany once noticed temporary glitches in their experiment, and then determined, to their relief, that Pauli, at the time, had been passing through the city on a train. Pauli was also noted for being extremely intolerant of shoddy science, and he was sometimes called “the conscience of physics” for his willingness to call a spade a spade. Even worse than bad science to Pauli was pseudo-science, claims so vague and unfounded that they could not even be tested. He said of one such paper, Das ist nicht nur nicht richtig, es ist nicht einmal falsch! “That is not only not right, it is not even wrong!”

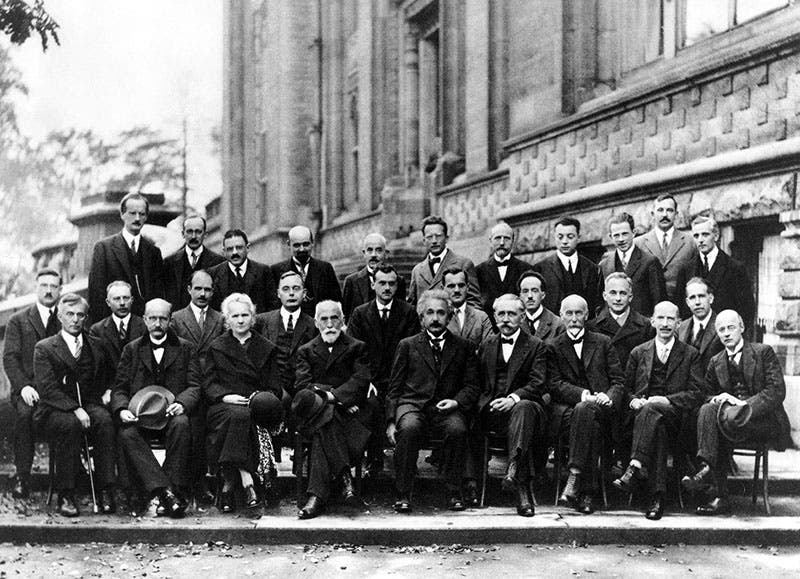

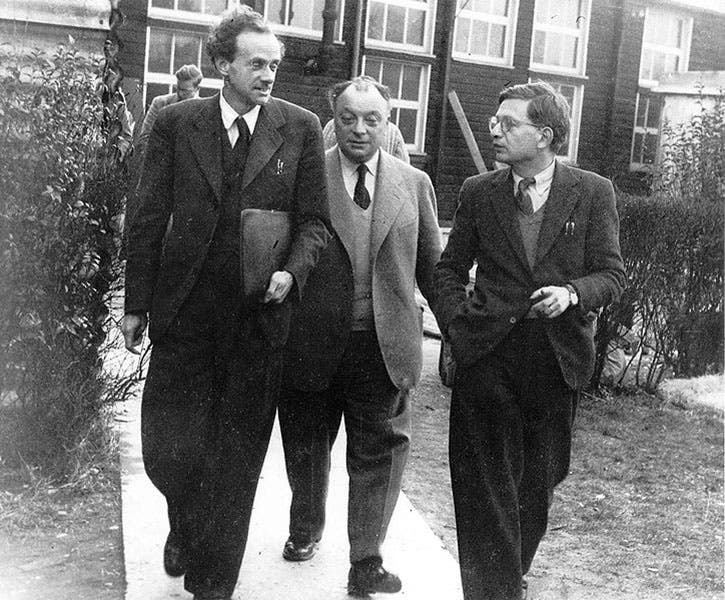

The photographs show: Pauli about 1924 (first image); Pauli and Albert Einstein in 1925 (second image); the Solvay Conference of 1927 – Pauli is fourth from the right in the last row, with Einstein seated front and center (third image); and a stroll with Paul Dirac (left) and Rudolf Peierls, early 1950s (fourth image).

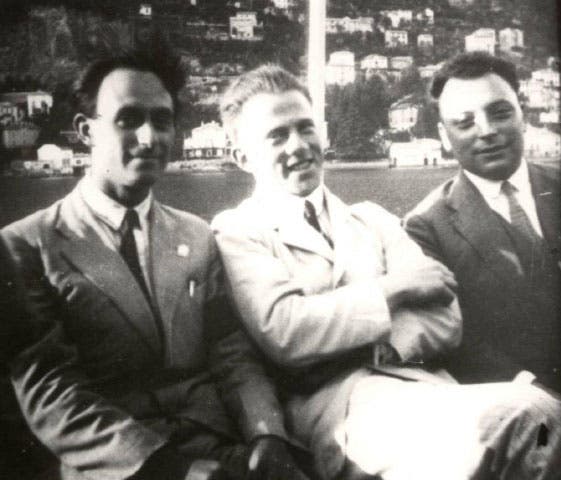

The last photograph is one of the great group portraits of the quantum era, showing Pauli, Fermi (left), and Werner Heisenberg at the inauguration of the Volta Museum at Lake Como in 1928. We used it as the lead image when Heisenberg was our Scientist of the Day just four months ago. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.