Scientist of the Day - Walter Charleton

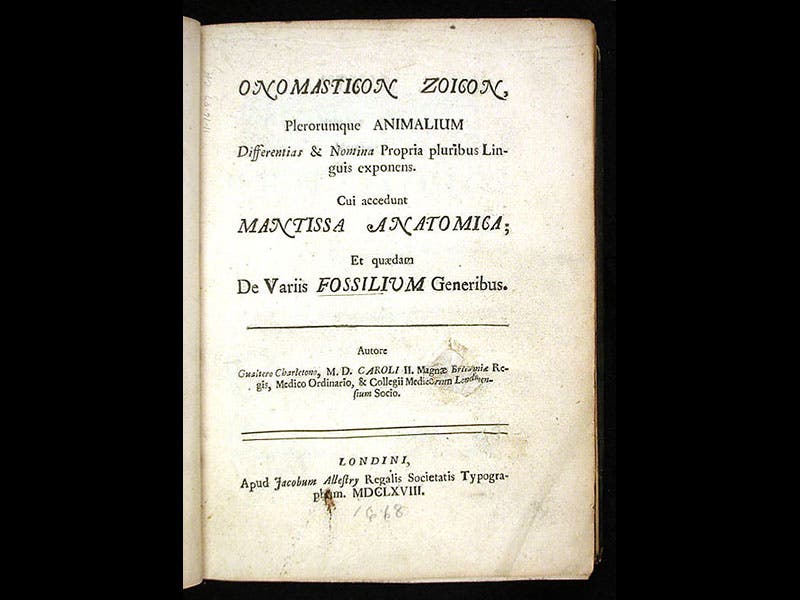

Walter Charleton, an English natural philosopher, was born Feb. 13, 1619. Charleton is best known for being the avenue by which atomism entered England from continental philosophy, as his Physiologia Epicuro-Gassendo-Charletonia (1654) introduced Gassendi and Epicurean atomism into Great Britain. But Charleton also wrote a much briefer work on natural history, Onomasticon Zoicon (1668, fourth image), that we are going to feature today. Here Charleton discusses a variety of animals and birds, but illustrates only a few, such as the bee-eater, hoopoe, and crossbill that we see above (in that order). What is interesting about the engravings is the way Charleton attempts to guarantee their veracity by giving details of their production. Concerning the bee-eater (Merops, first image), Charleton says he was given the specimen from Italy, and he had commissioned an effigy from an engraver, “so that it seems to be a true bird and not an engraved copy." As to the hoopoe (Upupa, second image), he points out that the specimen "was killed last winter ten miles from London and given to me; I have added his effigy, by a very skilled sculptor." This is a new thing in natural history illustration, depicting specific individual birds; earlier natural histories, when they depicted an animal or bird, used generic illustrations, which were often borrowed from earlier works. Charleton wants you to know that this is not any hoopoe or any beeater--these are the very specimens that he caught and studied, and the pictures are as true to life as his artists could make them. The Royal Society at the time was very concerned with the problem of verification when describing the results of experiments, and they took great pains to secure witnesses for their experiments. It would seem that Charleton was attempting to extend this verification process to the study of nature.

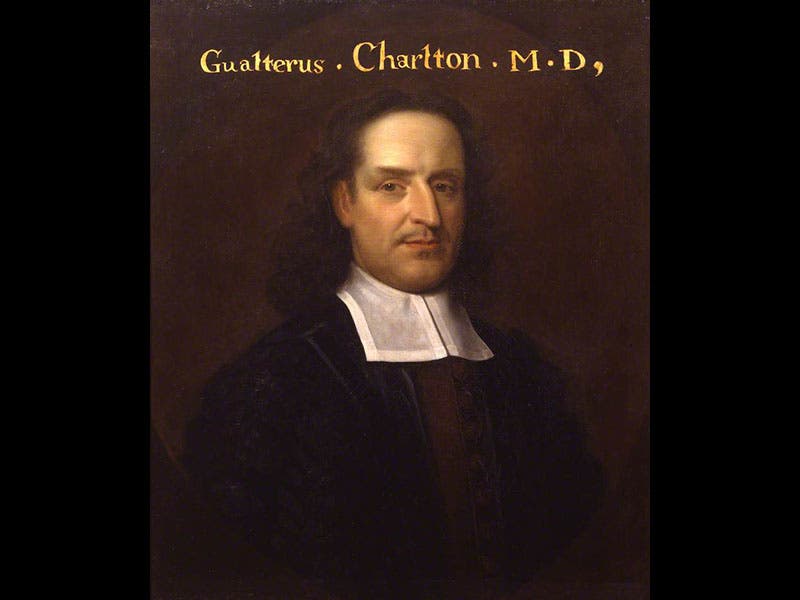

We have four Charleton works in our History of Science Collection, including the two discussed above. His portrait (fifth image) is in the collection of the Royal College of Physicians in London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.