Scientist of the Day - Vitus Bering

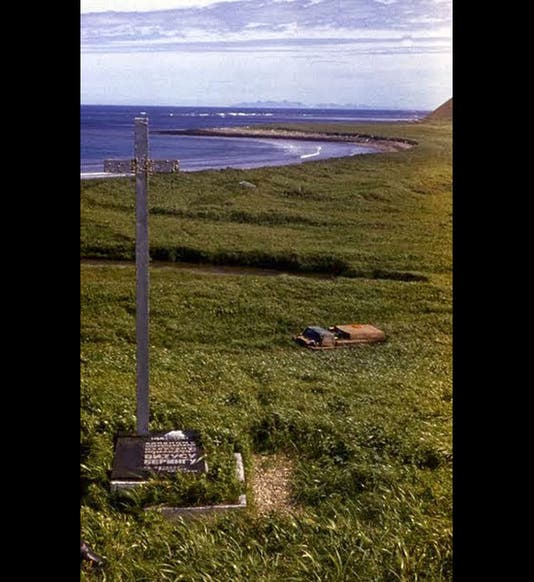

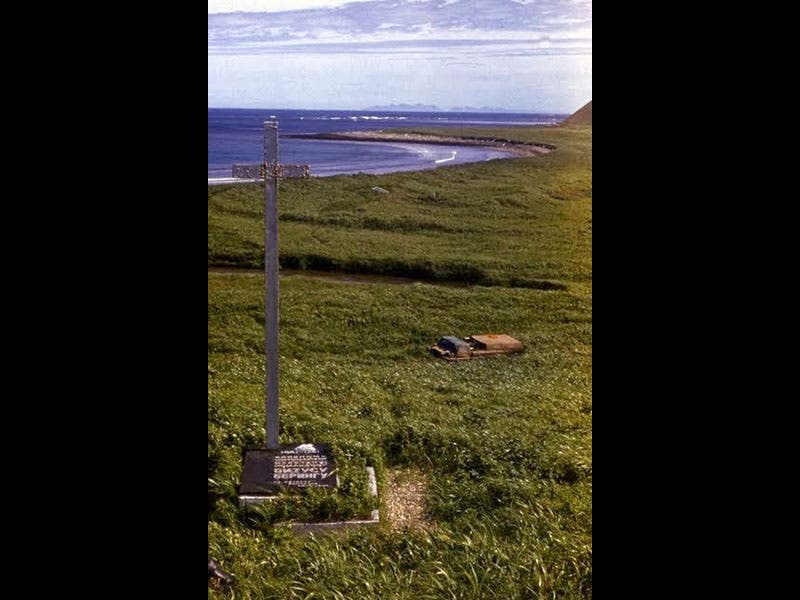

Vitus Bering, a Danish explorer, died Dec. 19, 1741, on a tiny island in the Aleutian sea, just east of the Kamchatka peninsula. Bering was on the second of two polar expeditions that were commissioned by the Russian Empire after the death of Peter the Great. On the first expedition, 1728-30, with a mission to explore the land and sea north of Kamchatka, Bering had discovered both the Strait and the Sea that now bear his name. He set about organizing a second voyage in the same area, which, after several delays, finally set out in 1741. This time he and his crew sailed east from Kamchatka and made it all the way to an island offshore of Alaska, which they sighted, thus discovering the northwest coast of North America. On the map above (second image), Bering’s second voyage is tracked by the red line at the bottom. On their return, Bering sailed by and discovered many of the Aleutian Islands. They made it almost back to Kamchatka, when they were shipwrecked on a small island, where they were forced to overwinter. Most of the crew were already suffering from scurvy, and 30 men died, including Bering. He was buried there, along with his crew, on the island that is now called Bering Island, in his honor. One of the survivors of that fierce winter was the expedition naturalist, George Steller, who lived to tell about his zoological adventures, which included the discovery of Steller's jay and Steller's sea cow.

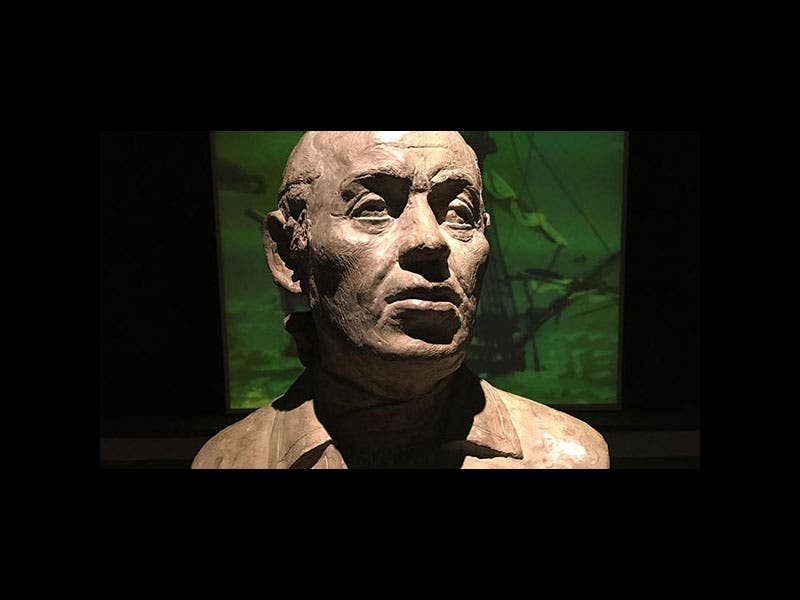

Vitus Bering is claimed as a national scientific hero by both Denmark and Russia, as you can see from this official Danish website, and this Russian one. It had always been assumed that Bering died from scurvy, like his crew, but in 1991, a joint Danish-Russian expedition traveled to Bering Island to search for Bering’s grave. They found it (and the graves of 5 other crewmen), exhumed the remains, and subjected them to forensic analysis. There were two noteworthy results. One, it was found that Bering did not die of scurvy, but of some other (unknown) cause. Second, he did not look at all like the picture that had been used to illustrate articles on Bering for 250 years, a round-faced, double-chinned individual (fourth image). The skull they disinterred from Bering’s grave was long and thin, and the bones strong and athletic. It is now thought that the round-faced man in the portrait was Vitus Pedersen Bering, a great-uncle of our explorer Vitus. Uncle Vitus was a historian, which, the Russian site proclaims, explains his weak, flabby appearance. I protest (weakly). Fortunately, the museum in Horsens, Denmark, Bering’s birthplace, has commissioned a new reconstruction based on the skull, so Bering has a new face, even if it has not yet been widely disseminated (third image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.