Scientist of the Day - Vesto Slipher

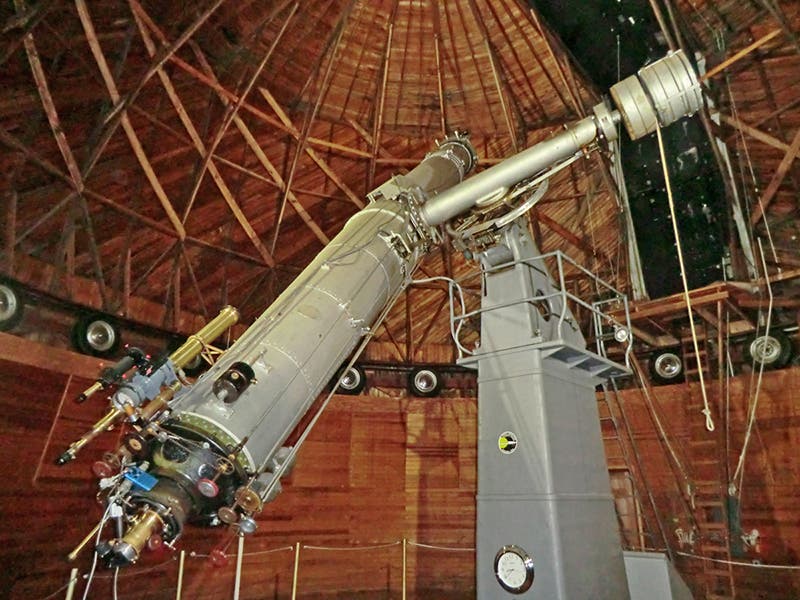

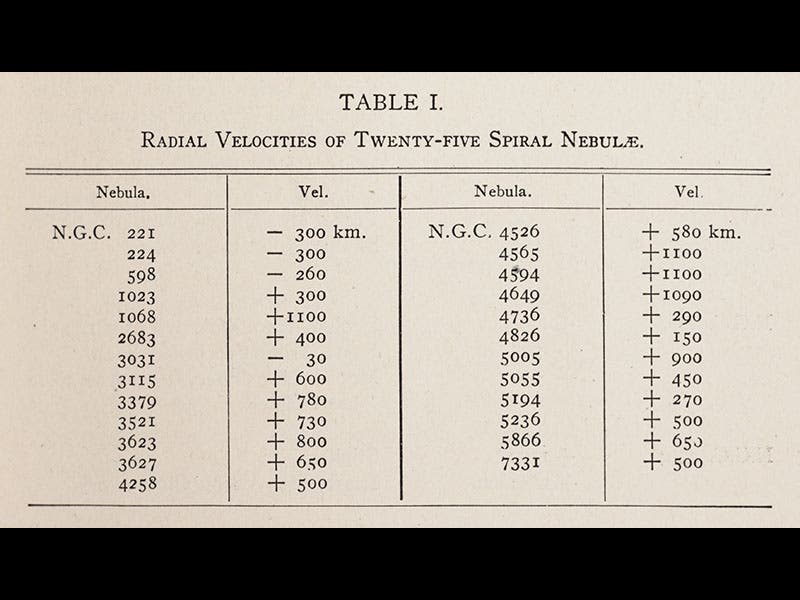

Vesto Slipher, an American astronomer, was born Nov. 11, 1875. Slipher worked at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, and in 1912, he was asked by the founder and director, Percival Lowell, to measure Doppler shifts of the most prominent spiral nebulae, using the observatory’s 24" Clark refracting telescope (first image). A Doppler shift is a displacement of spectral lines, caused when the object you are looking at is moving toward or away from you. Motion toward the observer produces a movement of the lines toward the blue end of the spectrum, or a blue shift, while motion away results in a red shift. It was expected that the motions of spiral nebulae would be random, and that red shifts and blue shifts would be present in equal numbers. Slipher started with the largest nebula, the great spiral in Andromeda, and found that it had a blue shift, corresponding to a motion toward us of some 300 km/sec. But as he looked at other spirals, he found that Andromeda was the exception--nearly all of the other nebulae exhibited red shifts, some of them quite sizeable. Slipher announced the results for 15 nebulae in 1914--12 were moving away from us, and for a total of 25 nebulae in 1917, of which 21 had red shifts. We see above the 1917 table of nebulae red shifts (second image); the ones with the greatest red shifts are moving away from us at speeds up to 1100 km/sec (684 mi/sec, or 2.5 million mi/hr).

This turned out to be a very important discovery, because a decade later, when Edwin Hubble had determined the distance to many of these spirals (now known to be galaxies), he realized that the further away a galaxy is, the faster it is moving away from us. In mathematical form, this became Hubble's law, and in popular form, it became the discovery of the expansion of the universe. It was announced in 1929, one of the great discoveries of modern cosmology. It would not have been possible without Slipher's determinations of red shifts. Many think he deserves much more of the credit for this discovery than he commonly receives.

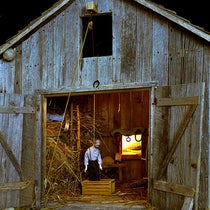

The other images show the dome at Mars Hill outside Flagstaff that houses the Clark refractor where Slipher made his spectroscopic measurements (third image) and one of the surprisingly few portraits we have of the younger Slipher, who did this work in his late thirties (fourth image). Slipher would later succeed Lowell as Director of the Observatory, serving until his retirement in 1952. The famous table of redshifts (second image) is from our copy of the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 1917, volume 56.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.