Scientist of the Day - Sarah Anne Drake

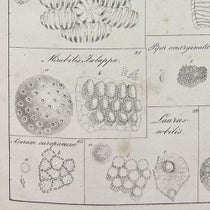

Sarah Anne Drake, an English botanical illustrator, was born July 24, 1803. One of her childhood friends was the sister of John Lindley, a botanist and artist with a special interest in orchids. When he recognized Sarah's artistic talent, he invited her into his household, and gradually she took over the illustration of his books. His Sertum Orchidaceum: A Wreath of the Most Beautiful Orchidaceous Flowers, was published from 1837 to 1841, and many of the lithographs were based on drawings by Drake. Orchids are inherently beautiful no matter who draws them, but Drake's paintings have a special quality, partially due, in my opinion, to the graceful way she arranged her specimens. Here are several of her plates, from the copy of Sertum Orchidaceum in the Missouri Botanical Garden Library: Onicidium pectorale, and Denobrium macrophyllum. A detail of the latter is our first image.

Lindley also took over the editorship of the Botanical Register in 1829, a journal founded by Sydenham Edwards in 1815 to rival Curtis's Botanical Magazine, and Lindley invited Drake to contribute illustrations to Edwards’ Botanical Register, as it was now called, which she did with enthusiasm. By this time, Drake had acquired the affectionate name of “Ducky”. Ducky Drake supplied over one thousand paintings to the Register over the course of 15 years. Here is one, another orchid, Cattleya Perrinii, from 1838.

Drake was further engaged to provide the illustrations for James Bateman's Orchidaceae of Mexico and Guatemala (1845), a work that is at once the largest and the scarcest collection of orchid lithographs ever published. There is a copy at the Missouri Botanical Garden, from which we took the illustration below, Cycnoches egertonianum. Here is a link to another, Stanhopea tigrina, if you find these as attractive as I do. We have a fine facsimile of Bateman’s book in our Library, and a facsimile of Lindley’s Sertum Orchidaceum as well, but not the original works.

In 1847, Edwards’ Botanical Register folded its tent, and Drake was suddenly unemployed. So she folded her tent as well and went home to Norfolk, where she married a wealthy farmer and pretty much disappeared from history, as happened all too often in Victorian England to women botanists and illustrators. All we know is that she died in July of 1857, at the age of 53. Drake was one of the 12 scientific illustrators featured in our 2005 exhibition, Women’s Work, although the books displayed of hers were all provided by the Missouri Botanical Garden Library.

When Drake was working for Lindley, illustrating his Sertum Orchidaceum, Lindley honored his artist in 1840 by applying her name to a new genus of orchids just discovered in Australia; he called them Drakaea, and at the time, there were three species known, and no one knew much about them. Here is one of the original three, Drakaea glyptodont, in a modern photograph. They are now referred to as hammer orchids. Why no one calls them Drake orchids, I could not say.

There survives a single portrait of Ducky Drake, sketched by one of John Lindley’s daughters, probably Sarah, in 1847.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.