Scientist of the Day - Samuel Smiles

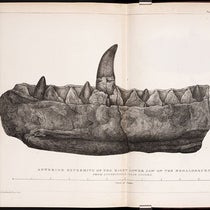

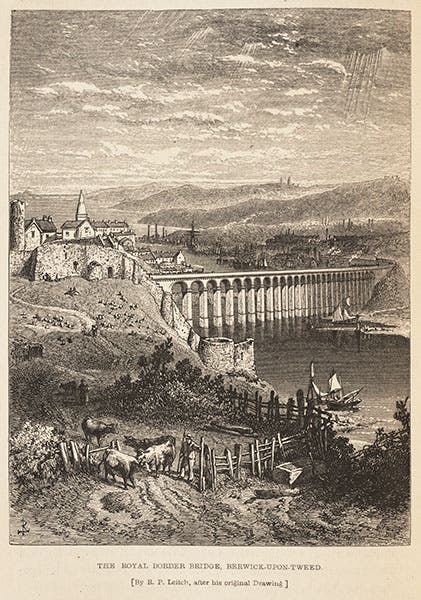

Samuel Smiles, a Scottish historian and author, was born Dec. 23, 1812. Smiles is well-known to historians of technology as the author of a series of books about great British engineers, starting with The Life of George Stephenson (1857), the eminent father of the British railway system, which blossomed into Smiles' three-volume compendium, The Lives of the Engineers (1861-2), which treats not only Stephenson and his son Robert, designer of the Britannia and Royal Border Bridges, but Thomas Telford, who built the Menai Straits bridge, and John Smeaton, erector of the third Eddystone lighthouse, the one that stayed put. A fourth volume was added in 1865, discussing Matthew Boulton and James Watt, the steam engine manufacturers.

Portrait of Robert Stephenson, engraving, from Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers, 1861-62 (Linda Hall Library)

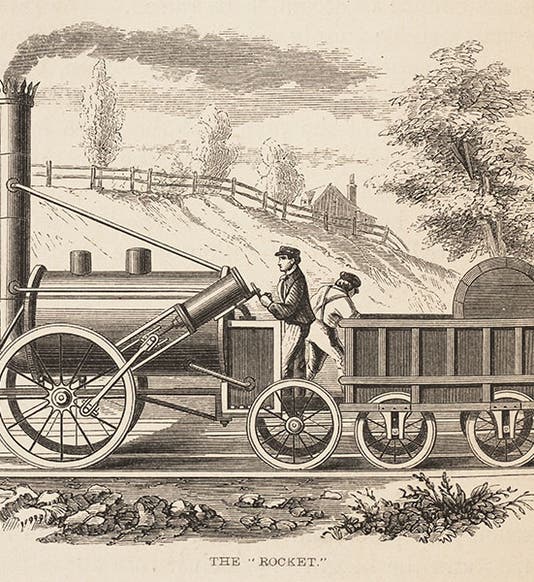

Smiles included many woodcuts and occasional engravings of his favorite engineers and their handiwork in his histories, so it is hard to do an exhibition about Victorian engineering without including multiple volumes of Smiles' book; we certainly utilized Lives of the Engineers in our exhibition Locomotion in 2008, curated by Bruce Bradley. We include here an engraved portrait of Robert Stephenson from that work, as well as wood engravings of The Rocket, the famous locomotive that won the Rainhill trials in 1829, and Royal Border Bridge in Berwick-upon-Tweed, designed by Robert Stephenson. Bruce selected Smiles’ image of The Rocket to grace the cover of his exhibition brochure.

The Royal Gorge Bridge, Berwick-upon-Tweed, wood engraving, from Samuel Smiles, Lives of the Engineers, 1861-62 (Linda Hall Library)

Historians of science are often unaware (as I was until a few years ago) that Smiles wrote another book that was far more popular and influential than any of his Lives; it was called Self-Help, and it was published in 1859. Many great books appeared in 1859 – Darwin’s Origin of Species, Edward Fitzgerald’s Rubiyat of Omar Khayyam, and John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty come to mind – but Self-Help outsold them all by far. We often find “Self-Help” sections in bookstores now, but Smiles invented the genre. The original Self-Help was not about building bookcases or darning socks; it was a guide to achieving greatness. The keys for Smiles were: keen observation, grit, the ability to focus on the problem at hand, and perseverance in the face of all obstacles. Not surprisingly, given his other interests, most of his examples of staying the course were drawn from science and technology. The book is available online, and if you flip to page 11 to the annotated table of contents, a host of familiar names will spring out at you: Newton, Galileo, Kepler, Josiah Wedgwood, William Smith, Charles Bell, and many others, each of whom noticed a phenomenon that needed to be explained, ignored the opinions of predecessors or contemporaries, and discovered “the truth.”

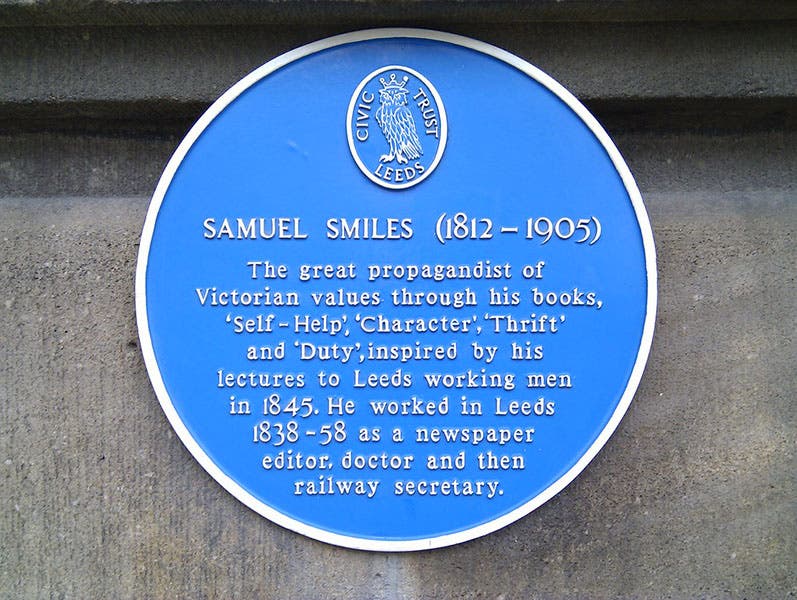

Smiles became both rich and famous as a result of Self-Help, and he wrote a number of other similar guides, such as Character (1871), Thrift (1875), and Duty (1880). We do not have any of these in the Library, but it seems to me we ought to acquire a first edition of Self-Help, given that nearly every European scientist of any significance makes an appearance somewhere in its pages.

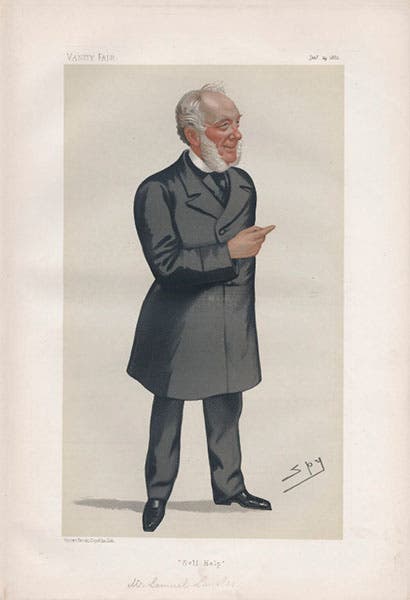

There is an excellen portrait of Smiles by George Reid in the National Portrait Gallery in London, but we thought we would include here a caricature that appeared in Vanity Fair in 1882, drawn by “Spy”, otherwise known as Leslie Ward, who drew nearly 2,400 such caricatures for the magazine over the course of 40 years. You can view two more Spy caricatures in our posts on William Crookes and E. Ray Lankester.