Scientist of the Day - Samuel F. B. Morse

Samuel F. B. Morse, an American painter and inventor, was born Apr. 27, 1791. We have not discussed Morse in this space before, because, quite frankly, he was not a very nice man, holding unsavory political and social views, and treating his colleagues shabbily in his attempt to claim sole credit for an invention that he did not even make. Still, the story of the invention of the telegraph is a famous one, with Morse usually cast in the leading role, so the least we can do is retell the story and reassign the roles more equitably.

Morse was first and foremost a painter, and not a bad one; someday we might look at that aspect of his life. But the telegraph story began in 1832, when Morse, on a ship headed home from London, learned from passengers about the new phenomenon of electromagnetism, which held out the promise of electric generators, electric motors, and electric telegraphs. Morse decided on the spot to devote himself to inventing a practical telegraph.

Morse knew next to nothing about electricity or electromagnetism, nor did he know that Charles Wheatstone and William Cooke in England were already developing a workable telegraph system, as were Carl Friedrich Gauss and Wilhelm Weber in Germany. Fortunately, back in New York, Morse made the acquaintance of Leonard Gale, a physics professor who knew quite a bit about electromagnetism, and who was a friend of Joseph Henry, who knew even more. As Morse began to do experiments, he discovered that he could not send a signal very far through a wire before it died out. It was Gale who told Morse about the relay, invented by Henry, which could take a weak signal and boost it, over and over again. Without Gale, and Henry's relay, Morse's telegraph would not have gone very far, literally.

Morse also acquired an assistant named Alfred Vail, who was a mechanical genius and who made much of Morse's equipment, including the telegraph keys, the signal detectors, and the relays. The really clever part of Morse's system was the code, which allows one to use a single wire to carry a message (other systems being devised often had a wire for each letter, or 26 wires in all!). The basic idea for the Morse code does seem to have been Morse's, but as to who developed the actual code, with a carefully chosen combination of dots and dashes representing individual letters, that is still up for debate – many think Vail was the one who worked it out, while others give the credit to Morse. If the experts can't decide, we will take no stand here.

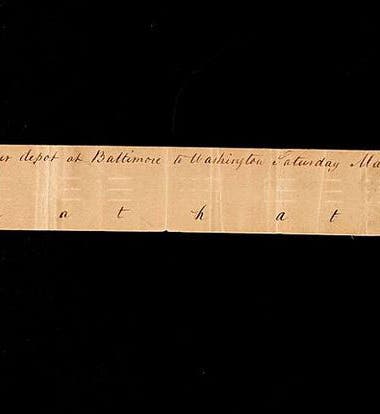

After successfully sending a message indoors over a 2-mile circuit in 1838, Morse applied for a grant from Congress to set up a test telegraph line, from Washington to Baltimore. He finally was awarded $30,00 in 1843, built his line, and as everyone knows, on May 24, 1844, sent the message, "What hath God wrought," from Washington, D.C. to his assistant Vail, 18 miles away in Baltimore. This was far from being the first telegraphic transmission – even Morse had done this long before, as had many others – but this is the one we all remember. The best part of the whole story is that the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian has the actual paper tape for May 24, 1844, impressed with the Morse code message that was sent, with Morse's translation written right on the tape in his own hand (first image). Now that’s a memento! (although, in truth, it seems like this might be a retransmittal from Vail to Morse made the next day, still an impressive document to survive). The Smithsonian also has a variety of other Morse-associated apparatus, including one of the telegraph keys used for that famous message, a device fabricated by Vail.

Telegraphy became a big success in the United States, and telegraph lines expanded right along with the railroads. Why Morse's name is the only one associated in popular opinion with this success is a mystery. Morse did not invent a single element of his telegraph system, unless we except the code – Gale, Vail, Henry, and others developed the transmitters, keys, recording instruments, and relays. Part of the reason for Morse's prominence in the story is just his persistent self-promotion and refusal to give anyone else credit. It is unfortunate when that approach pays off, as it too often does.

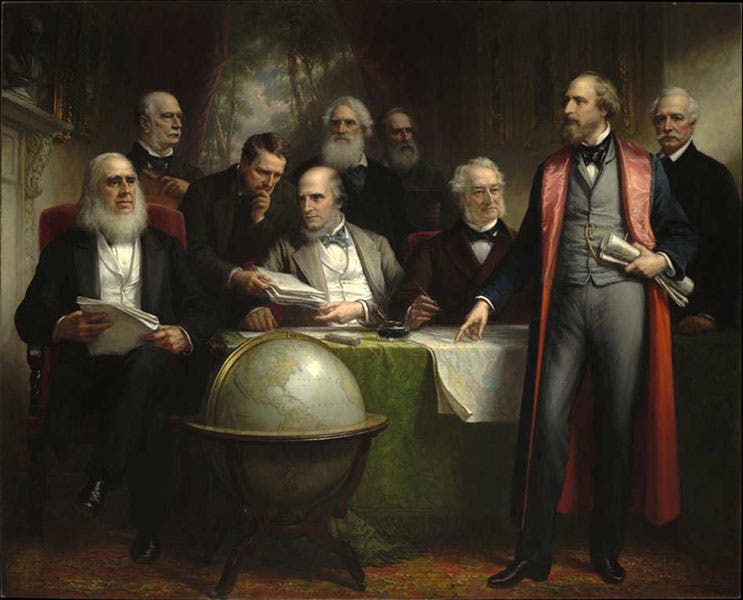

In line with our theme of the day, we show you a group portrait that includes Morse (second image). It was painted in 1895 by Daniel Huntington and purports to show us a meeting of 1854 in which proponents of a trans-Atlantic telegraph worked out their future plans. Morse is in center back, with the full white beard. Morse was indeed recruited by Cyrus Field (standing at the right) to add his name to the venture. But he played no other role than figurehead in the Atlantic Cable enterprise, and he was not at the meeting that Huntington was supposedly recording. So why was he shown? Because Huntington was an art student of Morse, and he apparently included Morse and himself (just behind Morse; he was not at the meeting either) because he felt like it.

Finally, we point out that one of the main reasons for the success of the American telegraph was something that no one foresaw – not Morse, not Gale, not Vail. Everyone planned on mechanically recording the dashes and dots in some fashion, such as on a paper tape, and then translating them back into letters one by one, as Morse had done on the May 24 tape. But it turned out that, if you used different pins for the dots and dashes, the dits and the dahs, then the code could be detected audibly, in real time, which sped up the whole process by at least a factor of ten. A good operator could translate a coded message as fast as you could send it, which was quite fast. And that is really why the telegraph became such a popular means of long-distance communication. It was fast, economical, and easy to use. That was not good news for the Pony Express.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.