Scientist of the Day - Rosalind Franklin

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

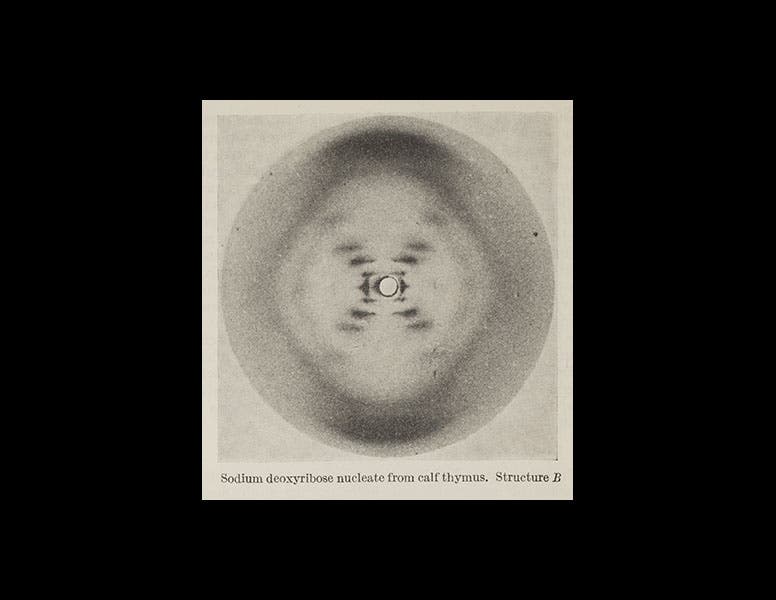

Rosalind Franklin, a British physical chemist, was born July 25, 1920. Franklin, working at King's College, London, under the supervision of Maurice Wilkins, developed improved techniques for producing images by X-ray crystallography. This imaging method, where X-rays are reflected off crystals and made to produce interference patterns, was actually invented back in 1912, and it allows one to "see" structures that are too small to be seen by visible light. In 1951, Franklin began applying her X-ray crystallographic methods to DNA. At the same time, up in Cambridge, James Watson and Francis Crick, a molecular biologist and a biophysicist, were trying to unravel the structure of DNA, in the hopes that the structure would shed some light on how genes replicate. Watson and Crick suspected that DNA had a helical form and by late 1952 were attempting to construct physical models, but without any real data to provide parameters for the model. Franklin and her assistant, Raymond Gosling, meanwhile had assembled a number of diffraction images of DNA, including an especially sharp one in the summer of 1952, now known as photo 51. From these, Franklin was able to measure distances between diffraction points that provided very useful information.

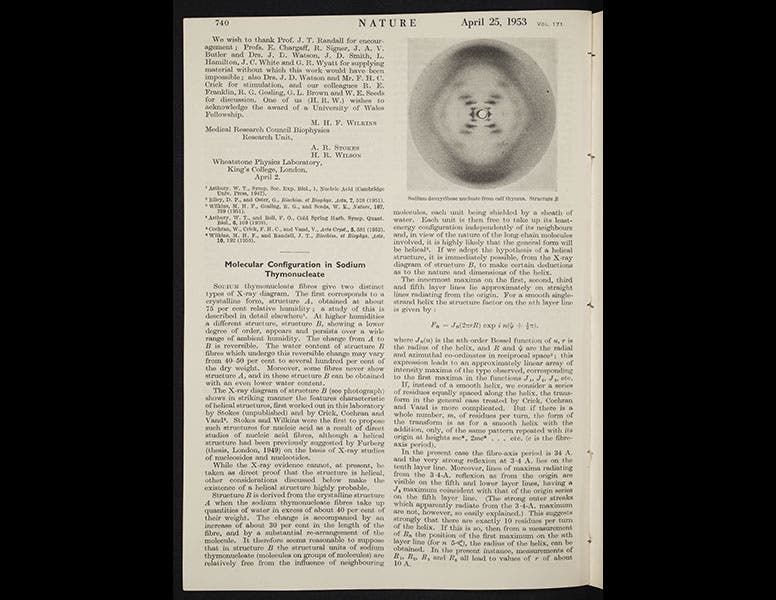

Franklin gave a paper presentation as early as the fall of 1951, in which she presented many of these detailed measurements; Watson was actually present, but apparently not paying attention. This information was eventually incorporated into a report that was distributed to various lab directors, including Watson's and Crick's supervisor at Cambridge. Then, in early 1953, Watson was shown photo 51 by Wilkins, and he immediately realized that the X-shaped pattern of dots could only be the result of a helical structure. He obtained the report with Franklin's measurements from his supervisor, and Watson and Crick were off to the races. By March they had a model, and by April of 1953, the famous double-helix paper was published in Nature. It was arranged that the Watson-Crick paper would be followed immediately by one by Wilkins, and another by Franklin and Gosling. Photo 51 was reproduced in Franklin's paper (second, third, and fourth images).

It is pretty clear that Franklin's work was an essential element of the discovery of the double-helix, and equally apparent that Franklin did not get the immediate credit she deserved for her contribution. The situation worsened dramatically when Franklin was stricken with ovarian cancer and died in the spring of 1958. This meant that she was not eligible for the Nobel Prize that was awarded to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins in 1962. And if matters could get worse, they did when Watson published his breezy The Double Helix in 1968, and generally belittled "Rosy", as he called her in the book (she was never known by that name). In an epilogue, Watson was much more generous to Franklin and praised her work and her personality highly, but readers tended to take away impressions shaped by the disparaging remarks Watson made in the early part of the book. For the next 20 years, the public unfortunately saw Franklin the way Watson described her in 1953.

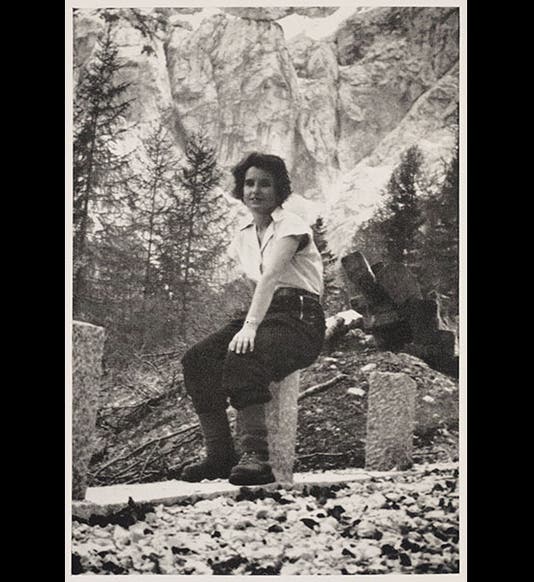

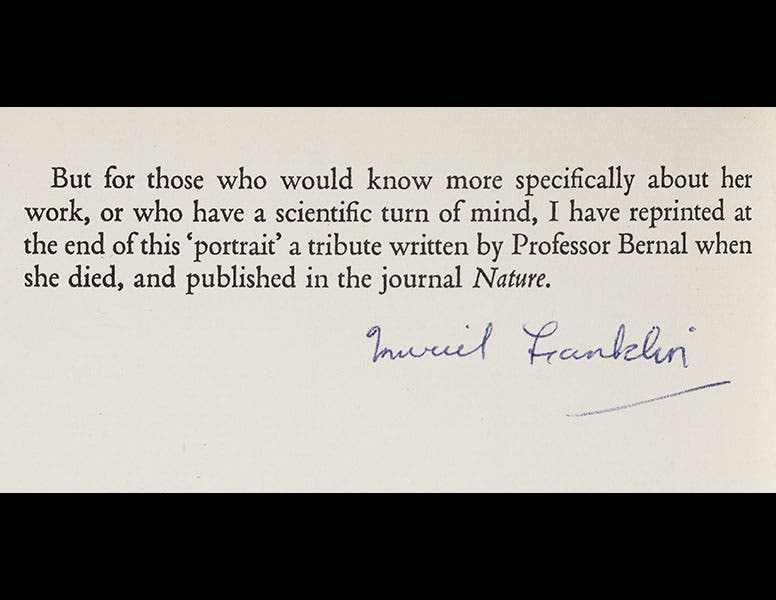

Happily, these days, Franklin's reputation has pretty much been redeemed; there have been several good biographies, a number of television documentaries, and there are laboratories and even a university named for her worldwide. Franklin's papers are all at Churchill College Archives, Cambridge, and one of the documents there is a slim pamphlet written by her mother, Muriel Franklin, probably around 1963 and privately printed. It is mostly about Rosalind's childhood – who would have guessed that Rosalind liked building Meccano sets – and her final years, and was clearly a labor of love and heartbreak by her mother. We recently acquired a copy of "Rosalind", signed by Muriel – to our knowledge, the only other existing copy – and we show three images from it above, including the portrait that begins our piece.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.