Scientist of the Day - Rosa Bonheur

French animalier Rosa Bonheur, born March 16, 1822, not only painted a menagerie’s worth of farm and wild animals over the long course of her celebrated career, but also kept a large number of domesticated “boarders,” as she liked to call them, at her home on the edge of the Fontainebleau forest. Her corrals enfolded horses, sheep (as many as forty at a time), goats, and deer, along with boars, otters, rabbits, and even lions (first image). She doted on a few lapdogs, too, and kept cages full of songbirds in her bedroom.

Horses established Rosa Bonheur’s international reputation. She completed her enormous canvas, The Horse Fair (second image), which now hangs in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, in 1853. It capped two years of work sketching skittish animals at the horse market on the Boulevard de l’Hôpital and watching dissections in slaughterhouses. She protectively disguised herself for these activities by dressing in men’s clothing. Given that cross-dressing was illegal in Paris in the 19th century, she appealed for, and won, a special “permission de travestissement” from the prefecture of police. The rest of the time, she wore dresses, favoring the traditional style of her native Bordeaux (third image).

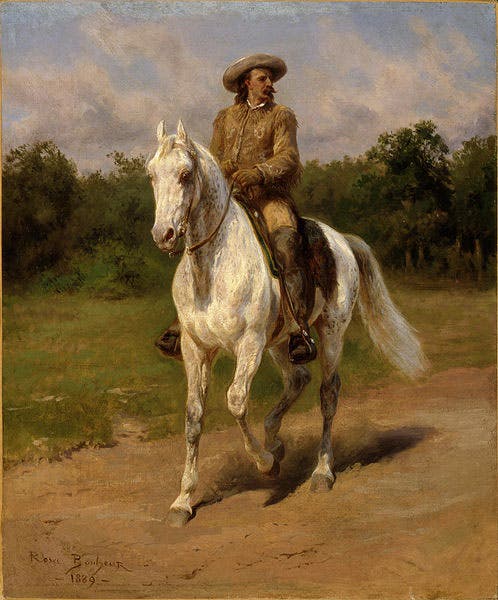

The Horse Fair, which stretches sixteen feet wide and eight feet high, was exhibited in Paris and Ghent before its triumphant tour through many cities in the United Kingdom and the United States. An American horse breeder was so taken with the image that he sent Rosa Bonheur a wild Percheron stallion. When the creature proved too spirited to serve her as a model, she turned him over to “Buffalo Bill” Cody, whose traveling Wild West Show happened to be in Paris at the time. She then painted a portrait of Col. Cody, astride his horse, of course, since a person without an animal never appealed to her as a subject (fourth image).

Rosa Bonheur claimed to have begun drawing animals as soon as she was old enough to hold a pencil. She said that the only way her mother could interest her in learning the alphabet was by challenging her to draw an animal for each letter. Her father, a landscape artist, recognized her talent, taught her to paint and sculpt, and urged her to enter her works in the annual Salon, a juried exhibition in Paris. But in spite of all his positive influence, Raimond Bonheur put his political ideals ahead of his family responsibilities: He moved into an all-male commune, leaving his wife to care for their four children in poverty. Rosa, the eldest, was only eleven when her mother died in these circumstances. The loss definitively shaped her ideas about matrimony and a woman’s right to develop her talents in a chosen profession. In her will, she described herself as “chaste and childless.”

In 1865, Empress Eugenie, wife of Napoleon III, personally presented Rosa Bonheur with the gold cross of the Legion of Honor, making her the first woman artist to receive that distinction. In 1894 she advanced from the rank of knight to that of officer, and proudly wore the medal when she posed for her portrait (fifth image) by Anna Elizabeth Klumpke. Rosa was friendly with all of the Klumpke sisters, two of whom, Augusta Klumpke and Dorothea Klumpke Roberts, have been featured here as Scientists of the Day. Dava Sobel, author of Longitude, Galileo’s Daughter, and The Glass Universe, is working on a biography of Dorothea Klumpke Roberts. Anyone with information about the Klumpke family is asked, please, to contact her through her website, www.davasobel.com.