Scientist of the Day - Richard Arkwright

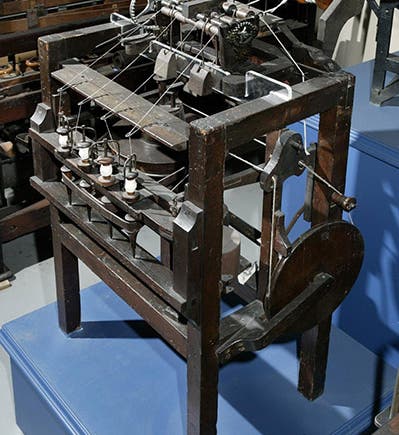

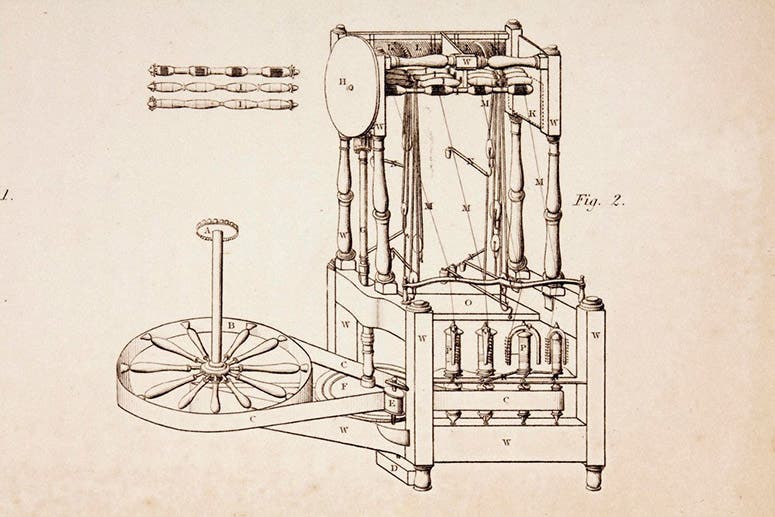

Richard Arkwright, an English manufacturer, was born Jan. 3, 1732. Arkwright is best known for his invention of the spinning frame, or water frame, which he patented in 1769, and which produced thread from carded cotton automatically, by machine. It was an improvement over the spinning jenny of James Hargreaves, because the thread was stronger. Before Arkwright, thread was spun in home shops by individuals working at a spinning wheel – one wheel, one thread. Now thread could be produced by machines, hundreds of spools at once, and skilled home laborers could be replaced by unskilled workers who just had to load carded cotton and exchange spools. We see here an original Arkwright water frame, built in 1775 and now in the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester (first image); Arkwright’s patent drawing of 1769 (third image); and a detail of a replica of an Arkwright water frame, showing the spinners that wind the spools, also in the Manchester museum (fourth image).

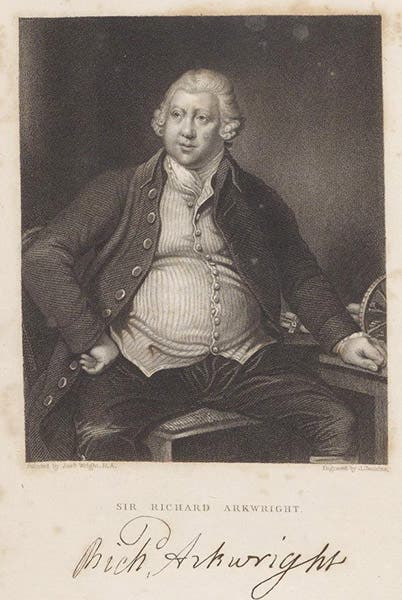

Arkwright set up a textile factory in 1771 at Cromford in Derbyshire, which was the first true factory; it employed thousands of women and children working around the clock. The spinning frames were powered by waterwheels, hence the term water frames. Competitors opened similar factories, using his invention without license, and Arkwright pursued infringement vigorously in court. Unfortunately, it turned out that most of what was original in Arkwright’s patents was the work of other men. His patents were challenged and overturned in court in 1781 and 1785. But it didn't much matter; he was knighted in 1786, and at his death (in 1792), Arkwright was worth over £500,000, which was close to being the equivalent of a modern billionaire. He had the social status to be painted by the great Derby painter, Joseph Wright, who even painted Arkwright’s factory at Cromford (fifth image). We show here an engraving of Wright’s portrait of Arkwright from our collection; the original oil is in the Science Museum, London.

Arkwright’s true invention was not the water frame, but the factory system. His Cromford mill was the first step in the industrial revolution that would reshape the landscape of England in the next half-century, especially when eventually married to the steam engine of Matthew Boulton and James Watt. Production was greatly increased with textile factories, but the social downside was severe, with women and children working 12-hour days doing repetitive tasks in unhealthy conditions. The industrial revolution was a very mixed blessing.

It is interesting that the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which included most of the luminaries of the Midlands, such as Erasmus Darwin, Josiah Wedgwood, and Boulton and Watt, never included Arkwright. I searched through Jenny Uglow’s rich study, The Lunar Men, looking for an explanation, and while I found considerable discussion of Arkwright (Watt, for example, was worried by Arkwright’s patents being overturned, afraid that his own might be in jeopardy), I did not discover why Arkwright never became a Lunar Man. Perhaps he was too busy. Or, since many contemporary accounts describe Arkwright as difficult and arrogant, perhaps he simply wasn’t wanted.

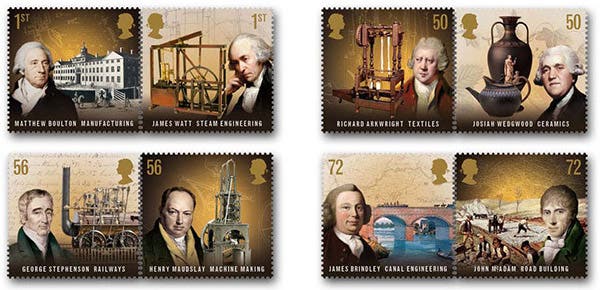

In 2009, British Royal Mail issued a set of 8 postage stamps, collectively called “Pioneers of the Industrial Revolution”. Arkwright was on one of the 50p stamps, where he joined Matthew Boulton, James Watt, George Stephenson, Henry Maudslay, Josiah Wedgwood, James Brindley, and John McAdam. As the links indicate, we have written posts on six of these, needing only Brindley and McAdam to complete the octafecta.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.