Scientist of the Day - Rene Antoine Ferchault de Reaumur

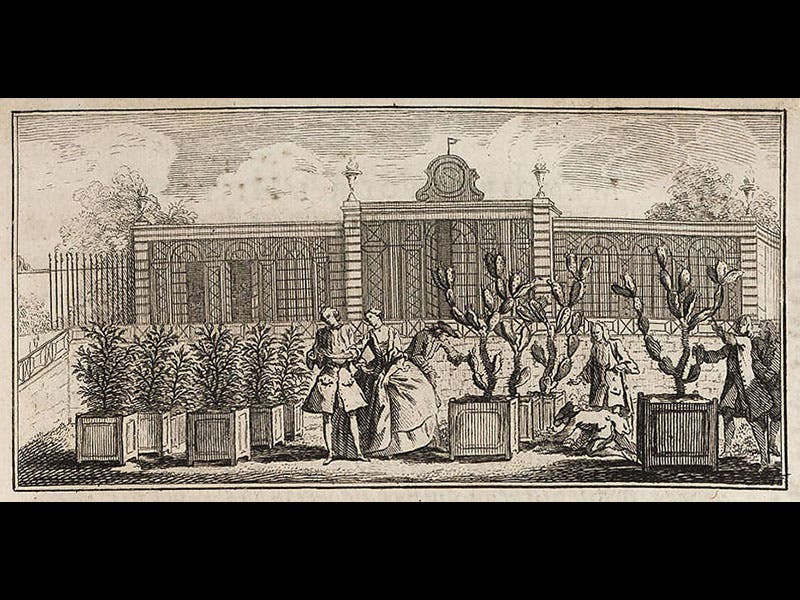

Réne-Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur, a French naturalist and inventor, died Oct. 17, 1757, at the age of 74. Réaumur made original contributions to every scientific field you can think of, developing methods of making steel, inventing a thermometer, and cultivating artificial pearls, but we speak today of his work on insects, which he published in 6 volumes as Mémoires pour servir a l'histoire des insectes, 1734-42 (with four more volumes intended). We have the set in the History of Science Collection. This work has inspired more ant men and bee buffs than any such work ever written, probably because Reaumur was such a close observer of insect behavior, or, as he called it, "industry". He included a long memoir in one volume on leaf-cutting caterpillars, detailing how they roll up leaves and glue them into a hollow tube, within which they can dine undisturbed, and how they can escape down a long silk thread when threatened, able to ascend to a continued supper when things calm down (second image).

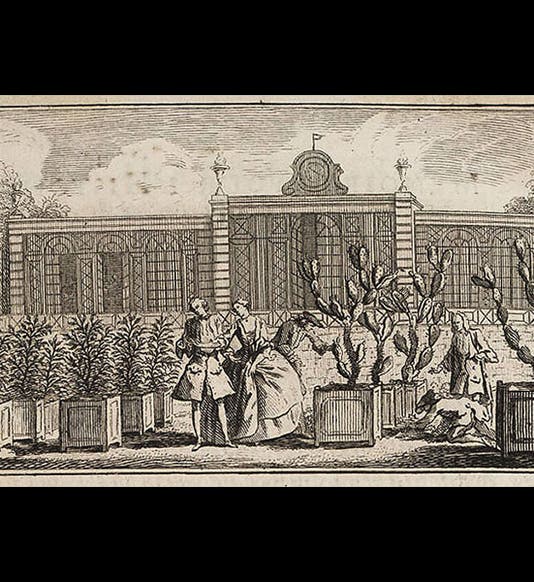

One of the insects that Réaumur treats is the cochineal, a scale insect that lives only on prickly pear, and that yields a brilliant carmine-red dye. In a vignette than opens his memoir, Réaumur shows us a small stand of prickly pears in Paris, with several courtiers collecting the insects. Interestingly, Réaumur did not care for traditional taxonomy (he was pre-Linnaean); he preferred to group organisms by their “industries”, so all leaf-rollers comprise one group, slave-making insects another, and parasites yet another. Reaumur wrote a sizeable memoir on ants, intended to be volume 7, but it was never published, or at least not until 1926, when the great William Morton Wheeler discovered, translated, and published it, as an homage to this pioneer of myrmecology.

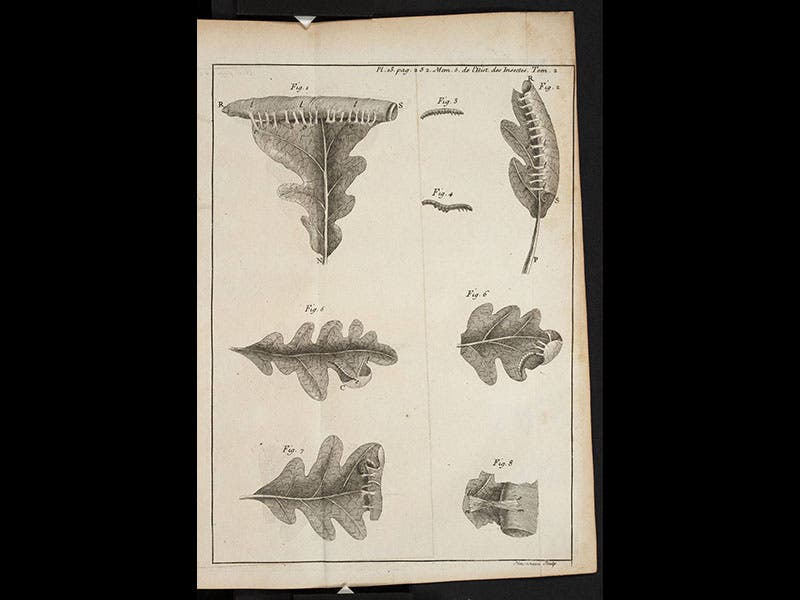

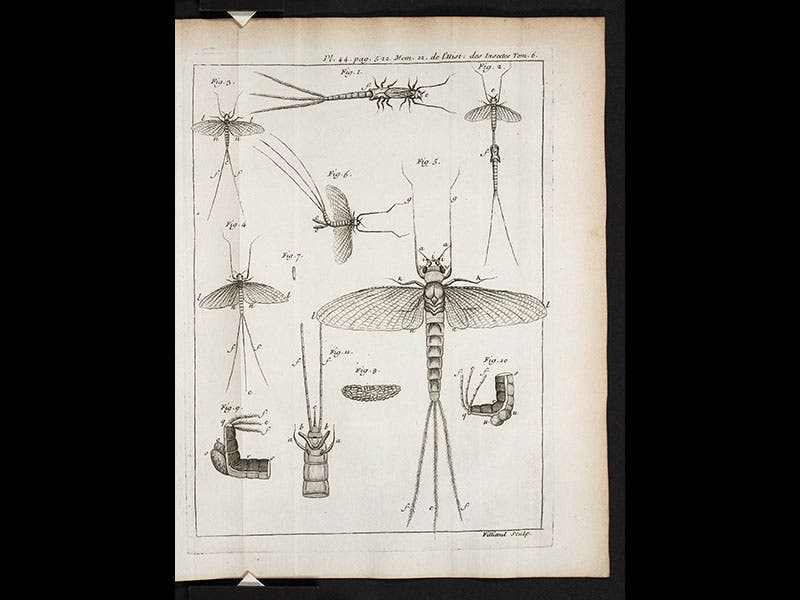

One of the delights of the Memoires des insects is that each volume begins with a head-piece made especially for that volume. In addition to the scene of the cochineal harvest, there is another that shows various would-be naturalists capturing insects with nets (third image), and another night scene that depicts moths attracted to a flame (fourth and fifth images). This is in addition to the scores of regular plates that depict a variety of insects in amazing detail, such as the may-fly (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.