Scientist of the Day - Rembrandt Peale

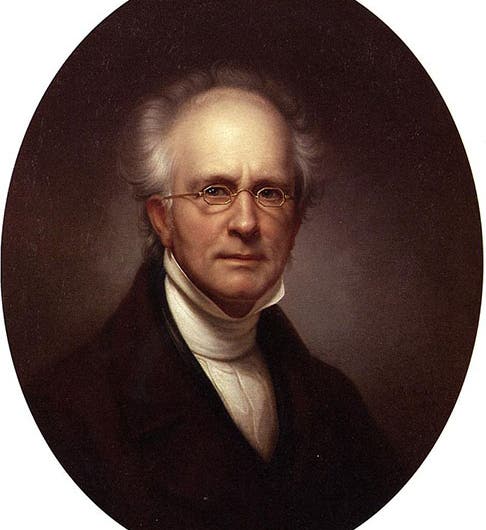

Rembrandt Peale, a Philadelphia portrait painter, was born Feb. 22, 1778. Rembrandt was the second eldest of the artistic sons of Charles Willson Peale; he was four years younger than older brother Raphaelle, six years older than Rubens, and 21 years older than Titian Ramsay (there had been a fifth son, Titian I, who died in 1798 at the age of 18). We have published posts on all of these except Rembrandt, and we are filling that lacuna today. You can see Rembrandt's self-portrait above, one of many he did over the course of his life, this one in 1846, at the age of 68. The well-known portrait of Rubens with a geranium, with which we began our post on Rubens, was painted by Rembrandt.

Charles Willson Peale, in addition to being a gifted portrait artist, also ran a natural history museum in Philadelphia, the country's first such institution. When Charles heard that some large elephant-like bones had turned up in a bog in up-state New York in 1798, he enlisted the family’s help in journeying north and digging up the rest of what proved to be the skeleton of a mastodon – actually one and 3/4 skeletons. Rembrandt took an active role in the excavation, and once back home, helped prepared the skeletons for mounting in the museum. Since bones were missing, especially the tusks and the top of the skull, Rembrandt had to engage woodcrafters to carve replacements.

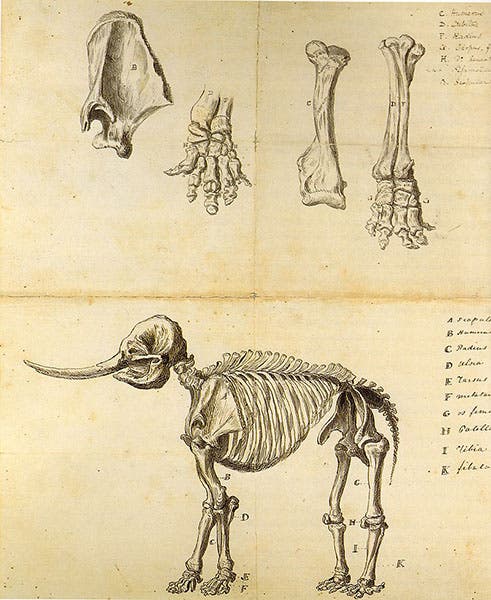

There is a drawing by Rembrandt that often illustrates accounts of the Peales and their mastodon; it is in the library of the American Philosophical Society; we see it above (second image). Historians had always assumed that this represented Rembrandt’s reconstruction of the mastodon, but recently a sharp-eyed scholar noticed that Rembrandt’s drawing is a copy of an engraving that appeared in a set of Histoires et Memoires of the Royal Academy of Science in Paris, published in 1734, and that it depicts, not a mastodon, but an elephant. Rembrandt undoubtedly made the drawing to help prepare the mount and perhaps to guide his woodcarvers. I made the mistake of calling it a mastodon drawing in my post on Charles, as you will see if you get to it before I can get a revised version in place.

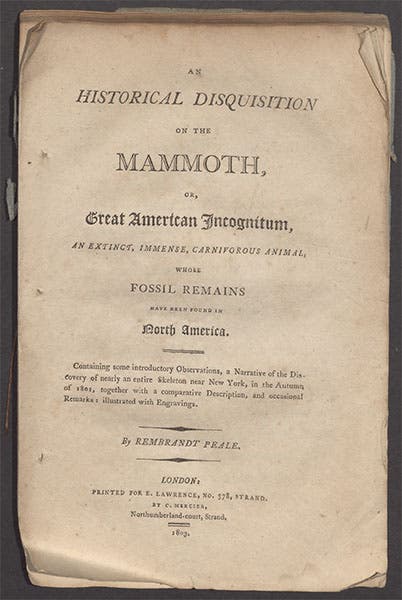

The first mastodon skeleton was put in place in the Peale Museum; the second one was taken by Rembrandt on a European tour that included London and was intended for Paris as well. While in London, Rembrandt published An Historical Disquisition on the Mammoth (1803), which we have in our collections; we show the title page here; the book is not illustrated (“mammoth”, by the way, was the term used at the time for all elephant-like fossils, before mastodon and mammoth were distinguished). The planned trip to France was cut short by the activities of Napoleon, and Rembrandt and his traveling mastodon returned home to Philadelphia, where he again took up his brush as a portrait painter.

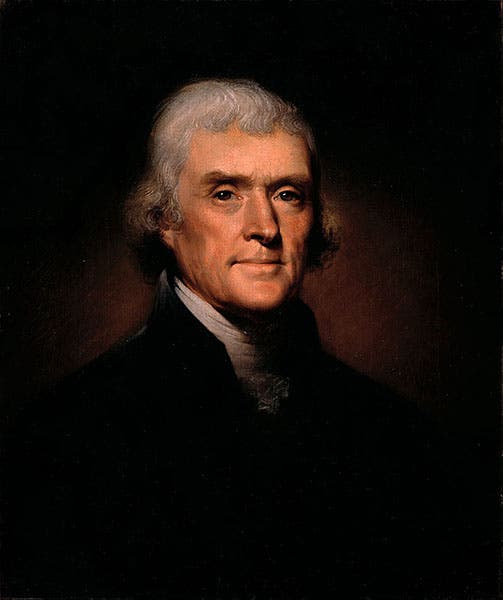

My three favorite portraits by Rembrandt are quite different from one another, in tone and in time. The best known is a portrait of Thomas Jefferson (he did several), this one painted early, in 1800, and now residing in the White House (fourth image, below).

The second is a portrait he painted when he did finally get to Paris in 1808, and shows Dominque-Vivant Denon, head of the Louvre (fifth image, below). We did a post on Denon once, because, before Napoleon put him in charge of the Louvre, he had accompanied Napoleon on his scientific invasion of Egypt in 1799 and published his own account in 1802, long before the official volumes began to emerge in 1809.

The third of my selected portraits shows Rembrandt’s daughter Rosalba (sixth image, below). It was painted in 1820 and is now in the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) in Washington, D.C. Isn’t that the loveliest of ways for a father to honor his daughter?

And speaking of SAAM, the museum is currently re-opening an exhibition that they planned to open last spring, just as the pandemic hit. It celebrates the scientific world of Alexander von Humboldt, and one of the objects they brought over from Germany for the exhibition was the original Peale mastodon that had been put together by Rembrandt.

The skeleton had been sold at auction, when the Peale Museum ran on hard times in the late 1840s, to the Hessisches Landesmuseum (the Natural History Museum of Hesse) in Darmstadt, and has been there ever since. Except for now. It looks quite splendid in its temporary new home in Washington (seventh image). I hope some of you get a chance to see it this time and admire Rembrandt’s handiwork and the beautiful wooden replacement bones. I had planned to suggest that, while you are there, you should look up Rembrandt’s portrait of his daughter. But I just discovered that it is not on view. You might complain to someone about that.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.