Scientist of the Day - Philip K. Dick

Philip K. Dick, an American science fiction author, was born Dec. 16, 1928. Arthur C. Clarke, an equally talented science fiction writer, was born the same day, 11 years earlier, in 1917. It was hard to choose, but we opted for Dick. Perhaps next year we will profile Mr. Clarke.

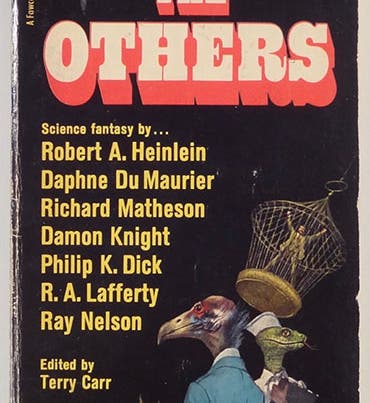

I well remember reading my first Dick short story; it was included in one of those SF theme anthologies that were so popular in the 1960s and 1970. This one contained stories about aliens, and was called The Others, edited by Terry Carr, and published in 1969 (first image). The half-title asked:

Are there other intelligent beings in the universe?

Are some of them watching us, waiting for their chance to take over?

Or are they already in control?

The very first story in this compilation was by Philip K. Dick and was called “Roog”. It was all of 6 pages long, about a dog named Boris who spent his week watching his owners carefully store up food in large outside receptacles, only to see the containers looted every Friday by the alien Roogs in their clanging trucks. It was driving the dog crazy, and he could not make his owners understand that they were being robbed, no matter how frantically he barked " Roog! Roog!" when the garbagemen began their weekly assault on the family larder.

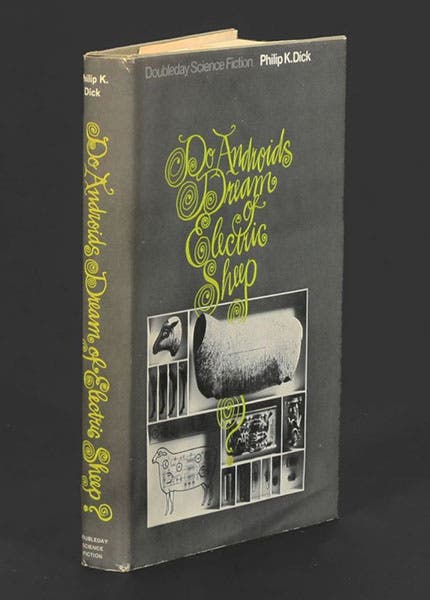

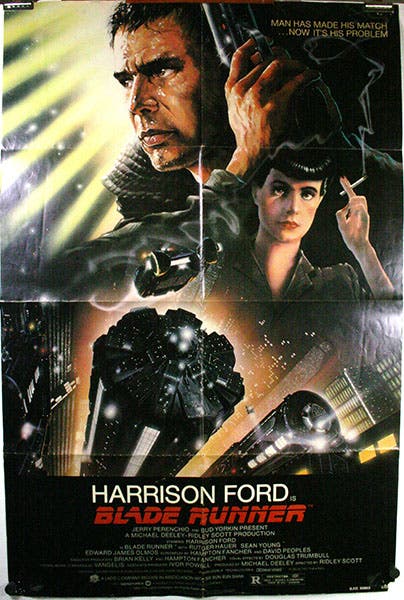

Well, that was certainly a different kind of alien story, written from the point of view of a dog who was trying to come to grips with an inexplicable reality and resorting to "invaders from space", as humans are all too wont to do. “Roog” was not only the first Dick story I read, it was the first story that Dick sold, back in 1951. The theme of this first story was already thoroughly “Dickian”, as I would discover. In "We can remember it for you wholesale," (1966) Dick wondered whether the human brain could tell the difference between an actual experience and one that has been implanted, and whether an implanted memory was any less real than an experienced one. A short novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968), pondered what it means to be human, and whether an android could ever cross the boundary between mechanism and human (third image). "Minority report" (1956) raised the question of whether, if we could see into the future, it might be possible to prevent crime, and whether a crime thus prevented was in fact a crime at all. And "The Adjustment Team" (1954) played with the possibility that our daily lives are constantly being manipulated by squads of angels in suits, following the intricate master plan of the Chairman.

If you are not an SF reader but some of this sounds familiar, it is probably because these last four stories (but not “Roog”) have been made into very successful films: Total Recall (1990, with a remake in 2012); Blade Runner (1982; fourth image); Minority Report (2002); and The Adjustment Bureau (2011). Other Dick stories have been the basis for less ambitious films – The Impostor (2001), Screamers (1995), Paycheck (2003), A Scanner Darkly (2006). Dick never lived to see the cinematic success of his stories; he died shortly before the release of Blade Runner in 1982. I am not sure any American author has inspired more movies than Dick, and more good ones – Elmore Leonard and Dashiell Hammett, by my count, lag some distance behind.

In 2006, an enterprising graduate student in computer engineering constructed a working android with the form and face of Dick himself. It was planned that Android Dick would take part in press panels for the release of A Scanner Darkly. The engineer, however, flying around the country with the head in a carry-on bag while the torso travelled below, one day left the bag on board a plane, and although it was momentarily recovered by the airlines, it soon disappeared and was never seen again.

The head was rebuilt in 2011, but we prefer to remember the original, travelling around the country all by itself, fully programmed with Dick’s life story, like something out of one of Dick’s own stories. What better memorial could a science fiction writer have than that.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.