Scientist of the Day - Peter Simon Pallas

Melissa Dehner

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Peter Simon Pallas, a German naturalist, was born Sep. 22, 1741. Pallas accepted an invitation in 1767 from the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences to come to Russia, and he spent the next forty years there, leading expeditions to much of unexplored Russia, and writing a series of works on the geology and zoology of the Asian mainland. We featured the expeditionary aspect of his life in a Scientist-of-the-Day feature several years ago. But we did not discuss there Pallas’s most famous discovery, a piece of outer space.

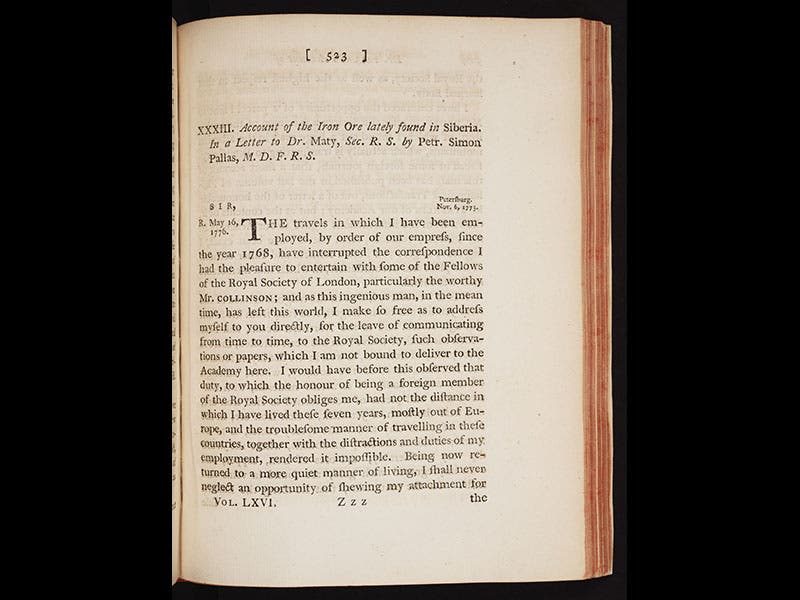

In 1772, one of Pallas’s field men came across a large rock sitting outside a blacksmith's shop in a little town in central Siberia (actually the stone had been discovered in the mountains in 1749 and hauled to the village, where Pallas’s assistant ran across it). He knocked off a chunk and took it to Pallas in Krasnojarsk, 150 miles away. Pallas was immediately impressed by its spongy, stony-iron structure, went to the site (we think), and arranged to have it transported to St. Petersburg. The journey took four years, as the meteorite weighed about 1700 pounds, and so they had to haul it by sleigh during the winter to the next large river, then raft it across the river in the summer, and then await the winter snows for the next leg of the journey. Once at the Academy of Sciences, fragments were sent to geologists around Europe, and Pallas published a paper about the stone in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London in 1776 (third image). He called it native iron and thought that nature had produced it in some strange fashion, not imagining that it came down from the skies. It was not until 1794 that the Pallas iron, as it came to be called, was invoked as a key witness in an argument by Ernst Chladni that such rocks are meteorites and have an extraterrestrial origin.

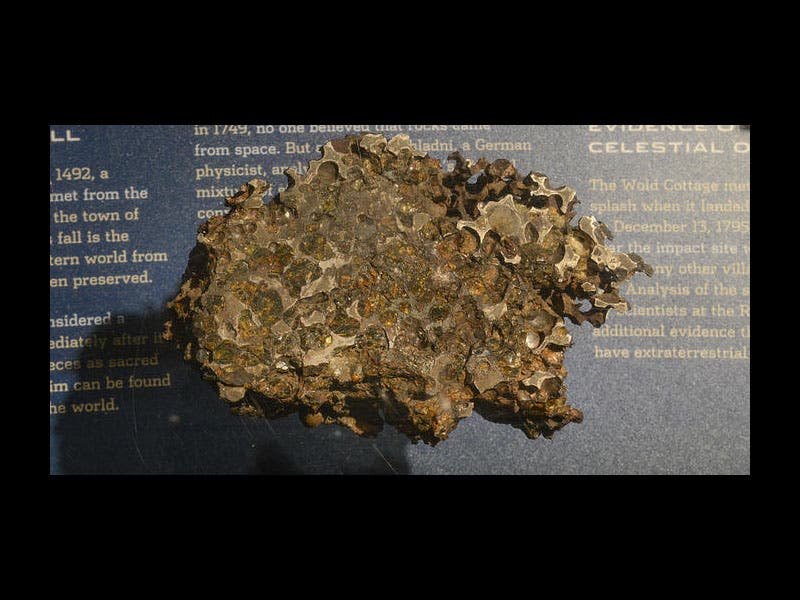

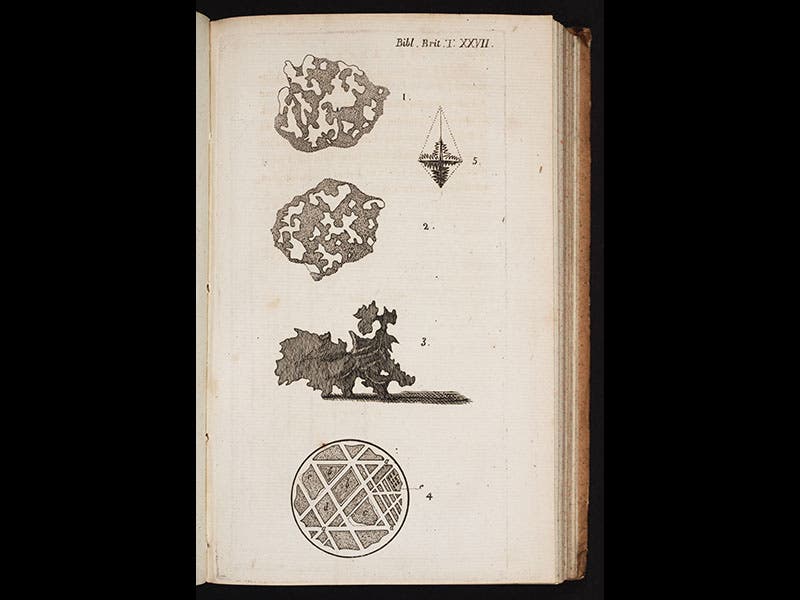

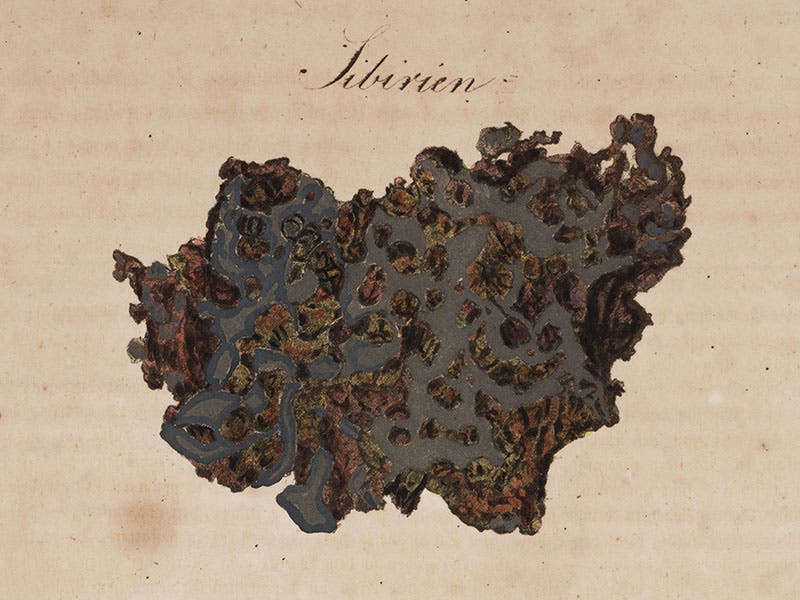

A piece of the Pallas iron was tested by William Thomson in 1804 and shown to exhibit certain geometric patterns when polished and etched by acid. Such patterns, only present in meteorites, are now known as Widmanstätten patterns, because for two centuries we thought that Widmanstätten, not Thomson, had discovered them. The first picture of such patterns was published by Thomson in 1804 in an obscure journal that we happen to have in the Library, and the object shown is a piece of the Pallas iron (fourth image). Another publication of 1820 has a hand-colored lithograph of yet another fragment of Pallas’s iron (fifth image). There is a similar piece in the American Museum of Natural History (second image). The core that remained (about 1100 pounds) after dozens of fragments had been removed is now in the Fersman Mineralogical Museum in Moscow; there seem to be no images of it online. It is customarily referred to as the Krasnojarsk meteorite. All meteorites with a similar structure (and there are many) are called pallasites.

A monument to Pallas was recently erected in Russia, at the site of the meteorite fall, but we prefer to show a different monument, a bird named for Pallas in 1820 by Coenraad Temminck. Pallas’s dipper is a charming creature that frequents streams and waterfalls; the exquisite graphite drawing above was freshly sketched for this occasion by our own Melissa Dehner (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.