Scientist of the Day - Patrick Russell

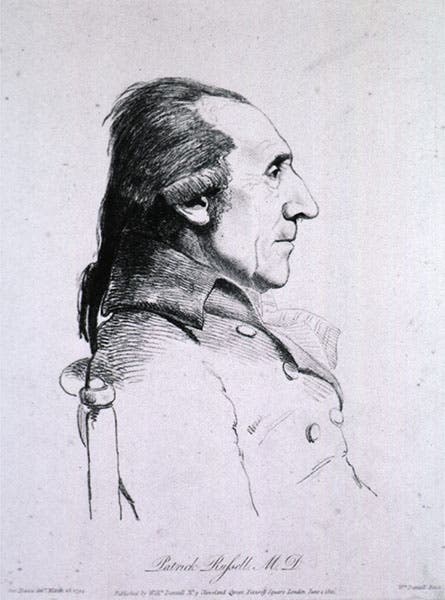

Patrick Russell, a Scottish naturalist, was born Feb. 6, 1726. Russell came from a wealthy and well-educated family of lawyers, and he himself studied medicine at Edinburgh. Patrick and his three brothers and half-brothers played an active role in what we might call Scottish enlightenment colonialism, in that all four siblings practiced their trades in British outposts such as Aleppo and India. Patrick's younger brother went to India as an administrator and Patrick went along to look after him. He arrived in India in 1781 and soon became company botanist for the British East India Company.

Perversely, he decided to study snakes. India has quite a few venomous snakes, including the famous Indian cobra, and Russell thought it would be helpful if he could find easy ways to distinguish those that were dangerous from those that were not. Russell collected live specimens of a variety of snakes from the local natives; he would listen to their tales about which species were the most deadly, and then experiment for himself. His standard of venomosity was the “chicken-minute”, as in: “When this snake bites a chicken, the chicken lives for 36 minutes.”

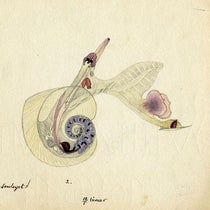

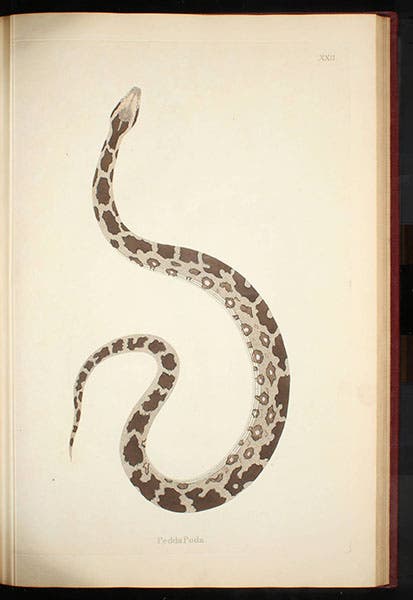

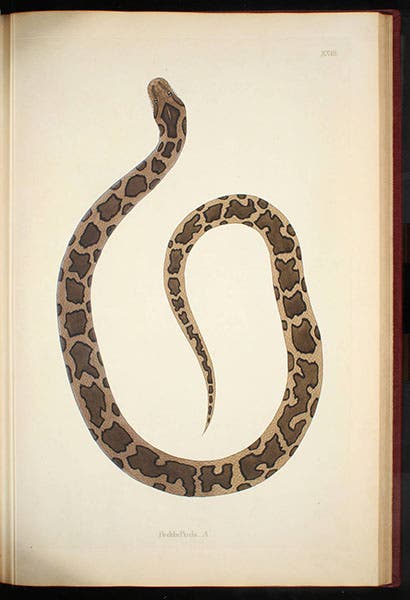

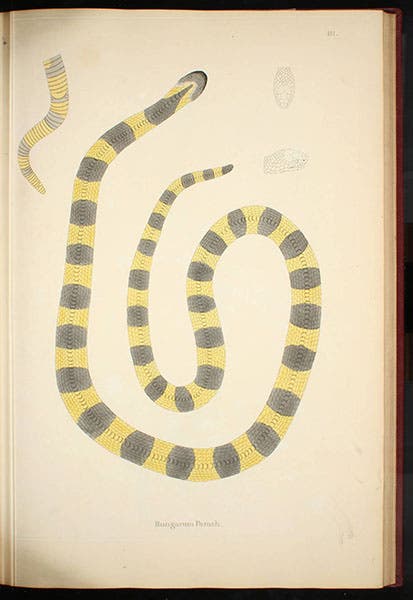

Russell returned to the British Isles in 1791 and began to collect his observations on the snakes of India into a book, the first part of which he published in 1796. An Account of Indian Serpents is a tall folio with 44 folio hand-colored plates of the snakes he collected. Although Russell does not talk about his illustrator, the first plate is signed "Skelton omnes fecit" – “Skelton drew and engraved all of these.” This is presumably William Skeleton, a noted Georgian engraver, who mainly illustrated travel books and scenic books and did not otherwise dabble in natural history, which I think shows in the plates, which are very two-dimensional. But they are hand-colored, which adds something to their attractiveness.

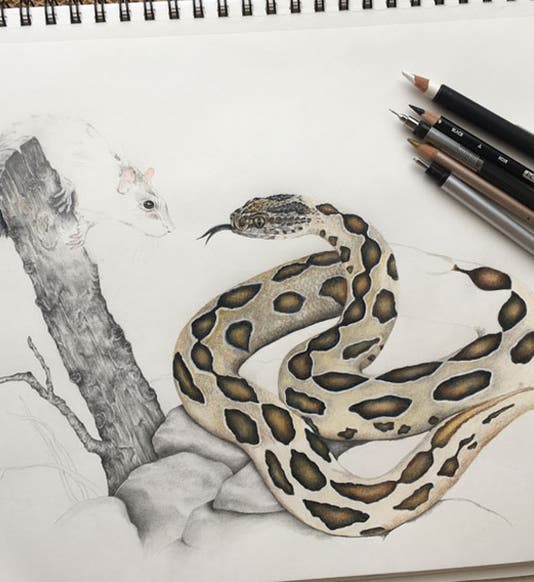

We show here four of those plates, which are identified only by native names; some, such as the rock python (third image) and the krait (fifth image) can be identified; others cannot, at least not by me.

Our last image, depicting “Katuka Rekula Puda,” an exceptionally venomous viper, is of interest, because the snake was later named Vipera russellii, Russell’s viper, in honor on our Scientist of the Day. The Library’s staff artist and designer, Melissa Dehner, who has illustrated a number of eponymous birds for this blog (see, for example, Pallas’s dipper), has been eager to tackle a snake, and she agreed to provide a newer version of Russell’s viper, this one contemplating a possible dinner in the form of a palm rat. She was not quite prepared for the scale of the challenge and has not yet finished the drawing. We thought readers might like to see what a work-of-art-in-progress looks like, and we include a photo of Ms. Dehner’s sketch pad as our first image. When she completes the drawing, we will update the image.

A second part of An Account of Indian Serpents was published in 1801/02, with 44 more plates, and two more parts appeared after Russell’s death in 1805. We have only the 1796 publication in our collections.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![“Katuka Rekula Poda” [Russell’s viper], hand-colored engraving by William Skelton, in Patrick Russell, Account of Indian Serpents, 1796 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/bd7847e2-e520-43fa-9f69-4104cb2dc90a/russell6.jpg?w=411&h=600&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)