Scientist of the Day - Otto Hahn

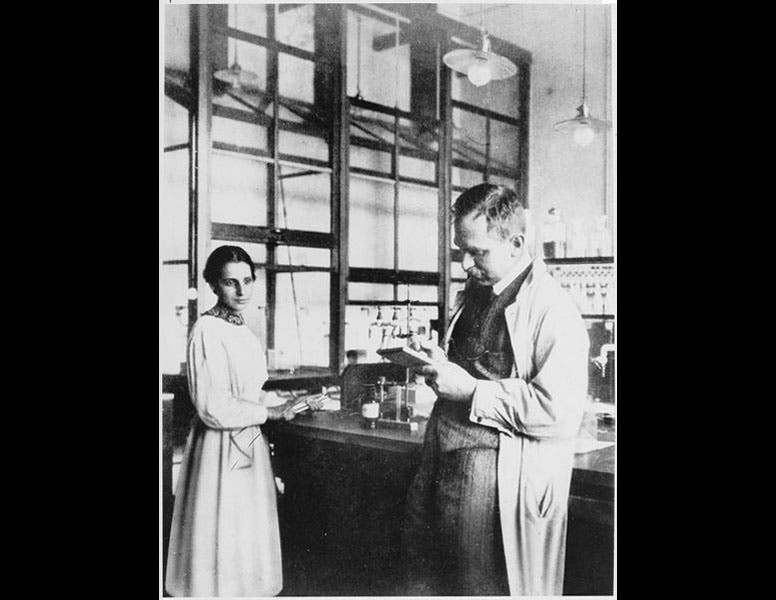

Otto Hahn, a German radiochemist, was born Mar. 8, 1879. For four years, from 1934 to 1938, Hahn pursued a delicate series of experiments in which he and his co-worker, Lise Meitner, along with a younger assistant, Fritz Strassmann, bombarded uranium with slow neutrons. A photograph shows Hahn and Meitner working in the lab at a much earlier time (second image). They were trying to make "transuranics", artificial elements heavier than uranium, which at the time was the last element in the periodic table. They created plenty of new elements, but they could not figure out what they were. Then, in the summer of 1938, Meitner, who was Jewish, fled to the Netherlands (with Hahn's help) and thence to Sweden; the work in Berlin was carried on my Hahn and Strassmann. In December, Hahn was perplexed that one of his new elements, which he originally suspected was a radium isotope, was displaying the chemical properties of barium, a rare earth that was much lighter than radium. He couldn't figure out what was going on, so he wrote about the mystery to Meitner in Sweden. Meitner at that time was being visited by her nephew, Otto Frisch, a young atomic physicist, and during a long conversation, the two came to the realization that the uranium atom must have absorbed a neutron and split into two much lighter atoms, one of which was barium. Frisch even coined the word "fission" to label the process, and the two worked out the physical details of what happened to a uranium atom when one added a slowly-moving neutron. The results of Hahn's experiment was published in a German journal on Jan. 6, 1939, and the Meitner-Frisch interpretation appeared in Nature a month later. Hahn had split the atom, and the world would never be the same.

In the fall of 1945, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for 1944 was awarded to Hahn. Neither Meitner, Frisch, nor Strassmann shared in the award. There has been a great deal of discussion ever since as to whether Meitner in particular should have received a share of the prize--she had worked with Hahn for over 30 years. Historians of physics tend to think Meitner was slighted here; historians of chemistry point out that this was an award in chemistry, given to a chemist for a chemical discovery; that physical interpretations of what is going on when fission occurs have nothing to do with it; and that Hahn was the only chemist in the world who could have done the experiments in the first place. The discussion will no doubt continue.

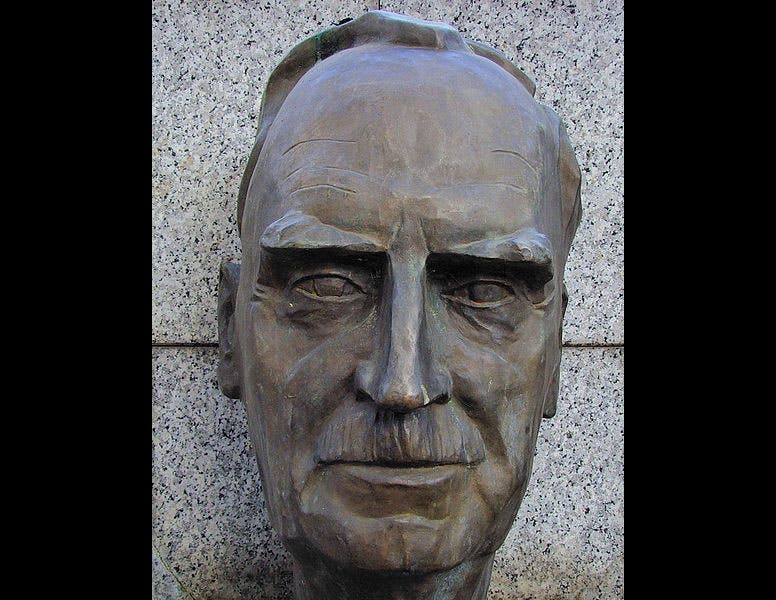

Hahn did his famous experiment when he was 59 years old--a splendid counter-example to the adage that physical scientists are washed up by the time they reach 30. And he lived 30 years after his great discovery, plenty of time to enjoy his late-arriving fame. The Deutsches Museum in Munich displays a replica of Hahn's experimental set-up of 1938 (first image). You will note that all of the apparatus fits on a kitchen table. A photograph of the table-top experiment is often introduced into discussions about whether, in this age of “Big Science,” an individual can still do cutting-edge experiments with just a little equipment and a lot of know-how. In point of fact, Hahn did his experiments in three separate lab rooms at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, on quite a number of tables. Nevertheless, since you could indeed put most of the equipment he used on one table, perhaps the point is still well taken.

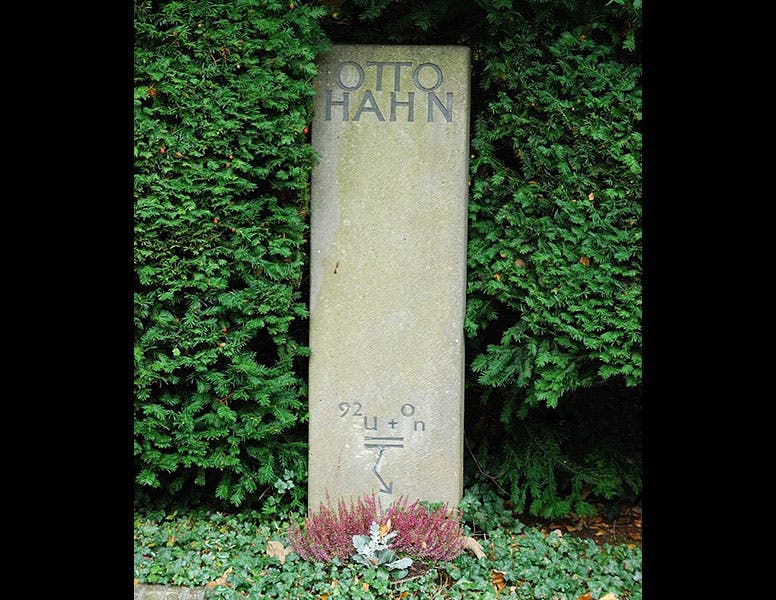

Hahn was buried in the Stadtfriedhof, a Göttingen cemetery that has no less than 8 Nobel laureates on its premises; his tombstone (fourth image) is simple and understated, like Hahn himself.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.