Scientist of the Day - Ole Brude

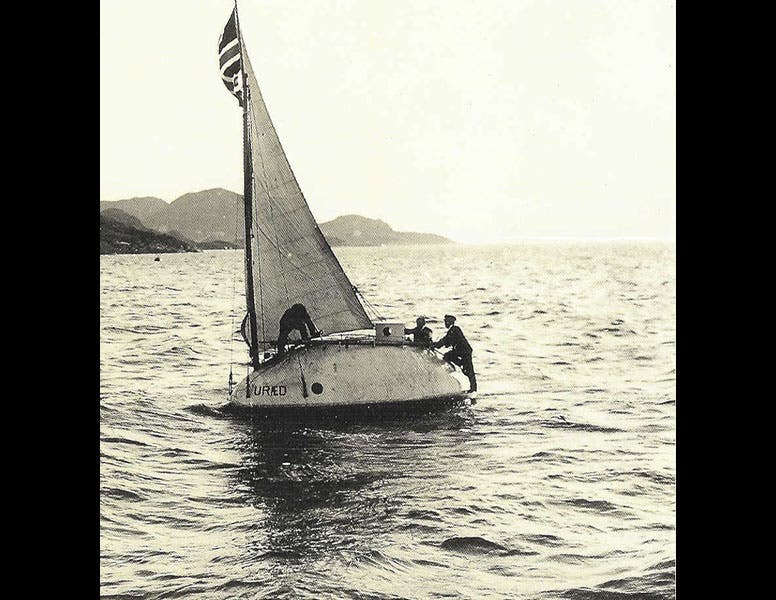

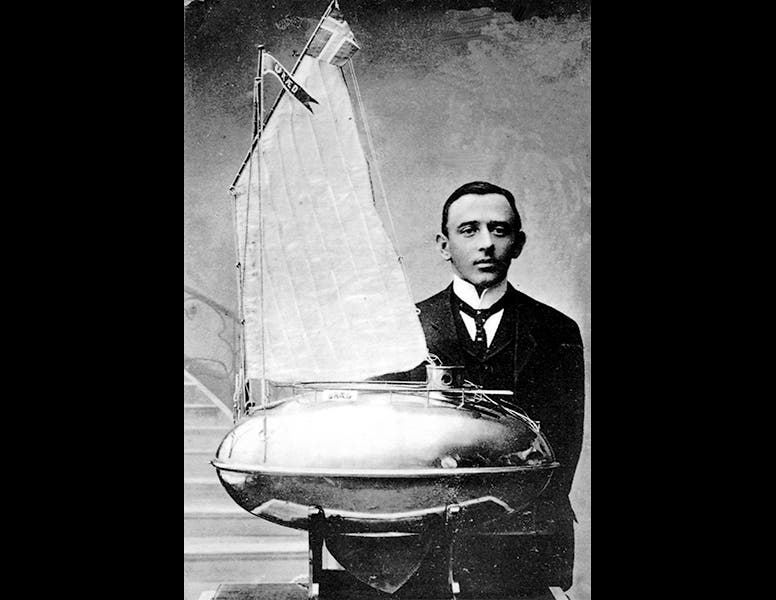

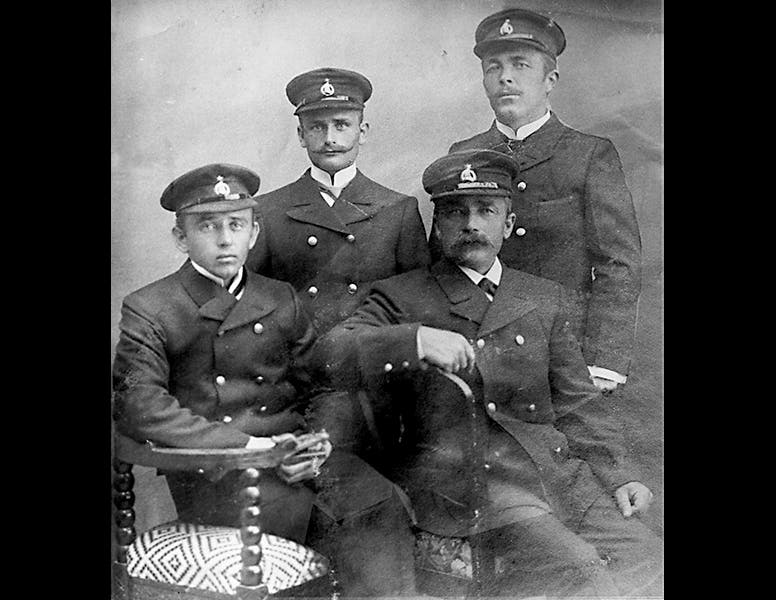

Ole Brude, a Norwegian sailor and lifeboat designer, was born Feb. 12, 1880. Brude went to sea at age 16, and he decided before he was 20 that the world needed a better lifeboat. So he designed one, an enclosed iron shell, shaped like an egg, with a sail to propel it, that Brude felt would give its occupants a much better chance at survival, since they would be protected from the elements in an unsinkable cocoon. We see above a photograph of Brude with a model of his creation (second image). Brude had a full-size version built, and upon hearing that France was offering a one-million-franc prize for an improved lifeboat, and that the judging was to be at the World's Fair in St. Louis in 1904, he decided to sail his egg across the Atlantic to New York to prove its sea-worthiness, haul it by train to St. Louis, and claim the prize. He persuaded three other crewmen to join him, several from his native seaport city of Ålesund, Norway (third image; Brude is at the left). The ship was christened Uraed, meaning “fearless,” and it departed Ålesund on Aug 7, 1904. Brude was planning on a three-month crossing, which would get him to the Fair before it closed.

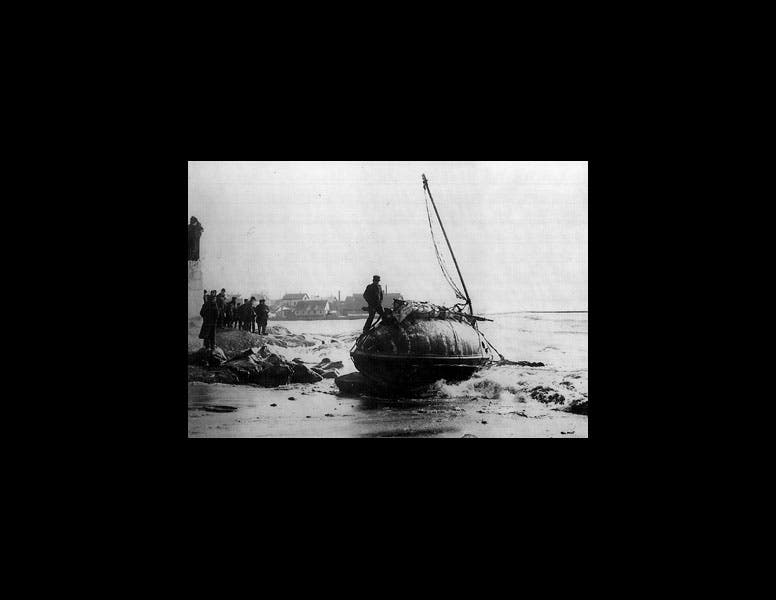

The first month of the journey went swimmingly, as they cleared Scotland and got almost halfway across the Atlantic. The egg was apparently quite a comfortable nest for the crew. It was some 18 feet long and 8 feet in width, and it did keep the water and wind out. But in September, they lost their mast, and progress slowed markedly, as they slowly bobbed their way westward with a jury-rigged replacement sail. As they neared the Atlantic seaboard, the weather changed for the worse, and they encountered storm after storm. They finally landed at St. John's, Newfoundland, on Nov. 15, which was a relief, but St. John’s was not New York, so they embarked again 10 days later, into even worse storms. On Jan. 6, 1905, they washed up on the beach at Gloucester, Mass, one day short of five months since they had left Ålesund (fifth image). The citizens of Gloucester were amazed when the battered steel egg disgorged four foul-smelling seamen, like something spewed from "the belly of a whale."

They never did make it to St. Louis, but the voyage of Brude's Egg was certainly newsworthy, and many headlines around the world lauded the pluckiness of Brude, his crew, and his craft. However, it took a long time for anyone to appreciate that Brude's lifeboat was really a significant improvement over the conventional open lifeboat that had been a mainstay for centuries. Not until the 1970s did enclosed lifeboats begin to appear on merchant ships. There is at least one modern company that manufactures enclosed lifeboats, and since they call themselves the Brude Safety Company, we know where they got the idea. They have put out a short video that pays homage to Brude.

Brude appears to be something of a minor hero in Norway, if the fact that he has his own song is any indication. If you like, you may listen to “Hurra for Ole Brude” here, accompanied by some still photos of Brude and the Uraed. And if you go to the Aalesund Museum, you can see a restored Uraed-- not the one Ole sailed in, but a later model, built around 1908, the only surviving specimen of Brude’s Egg (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.