Scientist of the Day - Ogden Rood

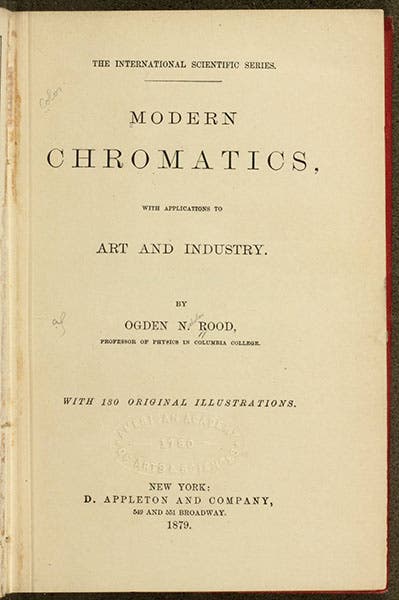

Ogden Nicholas Rood, an American physicist, was born Feb. 3, 1831. In 1879, Rood published Modern Chromatics, with Applications to Art and Industry, a lengthy title that would have been better phrased as Color Theory for Artists. There had been quite a few books published on color theory before Rood’s, but they tended to be written for other physicists and were lacking in practical applications. So the artistic community remained unaffected by the color theory of physicists.

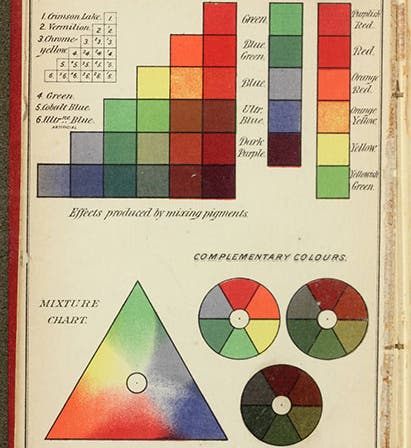

Rood not only explained complementary colors and how they might be useful for the painter, he also provided a color wheel that used artist’s pigments, rather than the physicist’s ideal colors, and he even prescribed what pigments should be on an artist's palette, and how they should be arranged (for those interested, his advised colors were, in this order from the thumb-hole: gamboge, Indian yellow, chrome yellow, vermilion, red lead, carmine, Hoffmann’s violet, cobalt blue, cyan blue, Prussian blue, and emerald green).

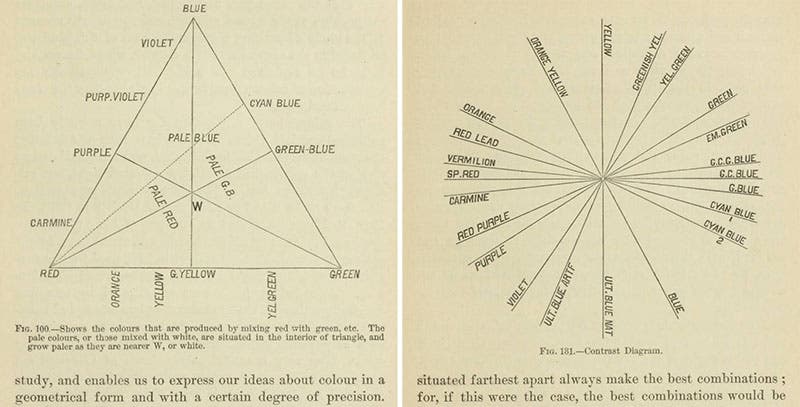

Two diagrams showing a color triangle (left), and a contrast diagram that uses artist’s pigments, from Ogden Rood, Modern Chromatics, 1879 (Linda Hall Library)

More significantly, Rood discovered that there was a big difference between mixing pigments on the canvas, and allowing the eye to do the mixing. He did experiments with spinning disks, in which two pigments were painted separately on the outer half of the disk, and were mixed together in the center. When the disc was spun, the eye saw two different colors, and the outer one – the one mixed by the eye – was usually brighter and more pleasing. The implication was that painters might be better off keeping pigments separated on the canvas.

Page of text discussing the effects of juxtaposing complementary colors in a painting, from Ogden Rood, Modern Chromatics, 1879 (Linda Hall Library)

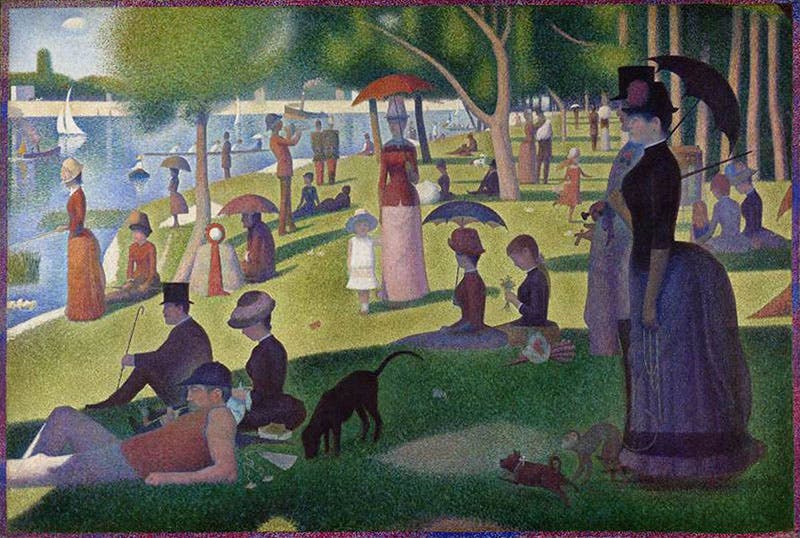

As soon as Rood’s book was translated into French, in 1881, the impressionists took notice. Indeed, it has been argued that Rood (along with his French predecessor Michel Chevreul) was responsible for the emergence of Neo-Impressionism and the work of its foremost exemplar, Georges-Pierre Seurat. Art historians argue about whether Seurat had read Rood when he painted A Sunday Afternoon on the Isle de la Grande Jatte (1884-86; sixth image), since Rood's palette had no earth-tones on it, while Seurat's did, but the painting certainly looks like a poster child for Rood's suggested method of painting with short lines and tiny dots of complementary pigments, which the eye would then combine.

If you want to see Rood’s book, you can come to our Library. If you want to see La Grande Jatte, you need take only a train-ride to Chicago, where it is on display in the Art Institute there.

I could not locate an oil painting of Rood. He was a painter himself – perhaps there is a self-portrait in watercolor lying about somewhere. The best I could do was this photograph published on the occasion of his death in 1902.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.