Scientist of the Day - Norman Lockyer

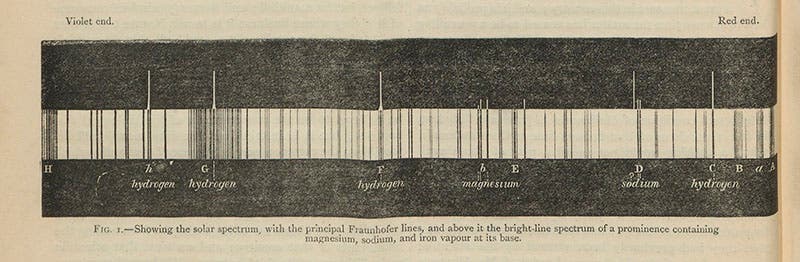

Norman Lockyer, an English astronomer, was born May 17, 1836. Lockyer was fascinated by the new science of spectroscopy, invented in 1859, and he was one of the early astronomers to take an interest in looking for spectral lines in the Sun. Joseph Fraunhofer had first revealed the dark lines in the solar spectrum in 1817 – they are still called Fraunhofer lines – but he predated spectroscopy, so he didn't know what the lines meant. After Kirchhoff and Bunsen demonstrated in 1859 that spectral lines are chemical signatures, it was possible to look for the presence of elements in the Sun by searching for the lines characteristic of those elements. Very quickly, the elements that make up the solar atmosphere, such as hydrogen, calcium, sodium, oxygen, and magnesium, were identified.

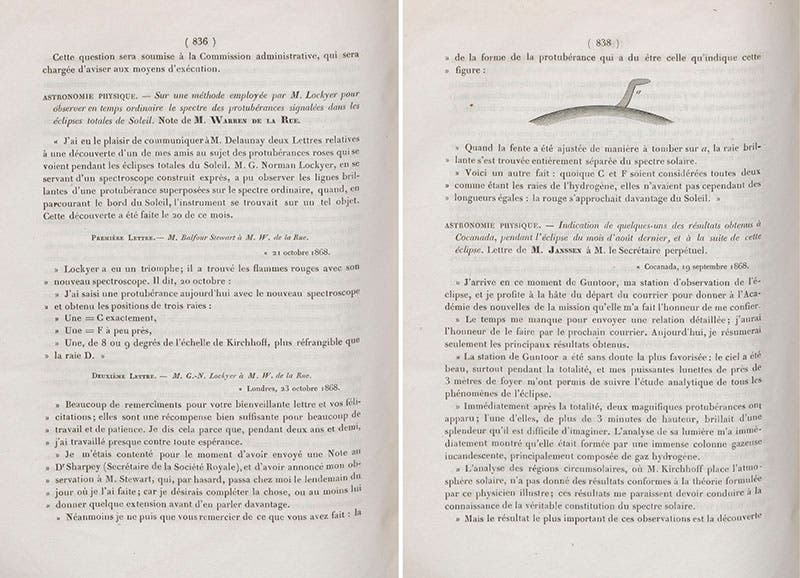

On Aug. 7, 1868, Lockyer (and many others) observed a total eclipse of the Sun, and Lockyer noted that at totality, prominences were visible that emitted bright-line spectra, rather than dark-line. This was the result of elements emitting light rather than absorbing it. Lockyer soon discovered a way to observe prominences without waiting for a solar eclipse, and on Oct. 20, 1868, he recorded three bright lines being emitted from a solar prominence. Two of them were in the position of known elements, but the third - a bright yellow line - was a little displaced from the two yellow sodium lines that Fraunhofer had labelled the "D" lines. Lockyer immediately sent off a letter to Warren de la Rue, which was read to the French Academy of Sciences on Oct. 26, 1868. Lockyer did not claim that the yellow line represented a new element, but he seems to have eventually suspected that this was the case, and when the hypothetical new element was named helium a few years later (by William Thomson, soon to be Lord Kelvin), he did not disagree. The actual element helium would not be found on Earth until William Ramsay identified it in 1895, which confirmed its existence in the Sun.

Ironically, a French spectroscopist, Jules Janssen, had also discovered how to see bright solar prominence lines without an eclipse, and he too sent a letter to the French Academy, written before Lockyer’s, but read moments afterward; both were published in immediate succession in the Comptes Rendus of the Academy. Janssen did not mention the bright yellow line in his paper, but he apparently saw it, and Lockyer and Janssen are usually credited jointly for the discovery of helium in the Sun.

The story of the simultaneous announcement of new prominence lines by Lockyer and Janssen is a familiar one in the history of astronomy, but nowhere online that we could find, has anyone reproduced the proceedings of the Oct. 26 session. We do so here, providing a look at the pages recording the Session opening (second image), the occasion of the reading of Lockyer’s letter (third image), and, immediately following, the reading of Janssen’s letter (fourth image).

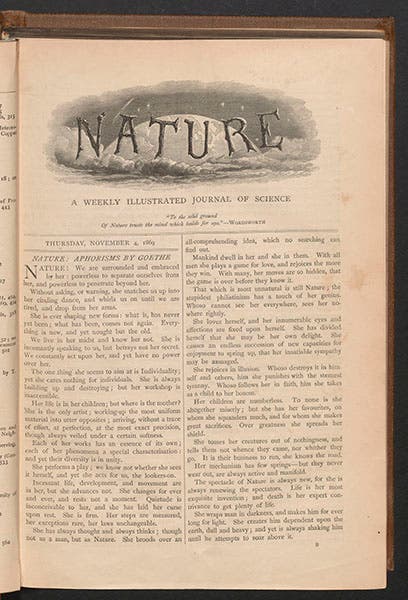

Lockyer had one other feather in his cap that we should mention: he founded and was the first editor of the journal Nature. In fact, he edited Nature for over 50 years and turned it into one of the foremost scientific journals in the world. The first issue appeared on Nov. 4, 1869 (fifth image), and interestingly, one of the first articles was by Lockyer himself, on the total solar eclipse of Aug. 7, 1868. In that article, he included a wood engraving of a dark-line solar spectra, above which he added the bright prominence lines that he had seen both during the eclipse and later.

You can see the double D line (or D1 and D2 lines) in the solar spectrum at the right, and just above it, and slightly to the left, the bright line that we now know represents helium, and that Lockyer (and Janssen) discovered. At the time, Lockyer treated it as just another sodium line, the D3 line. Its significance would be revealed soon enough.

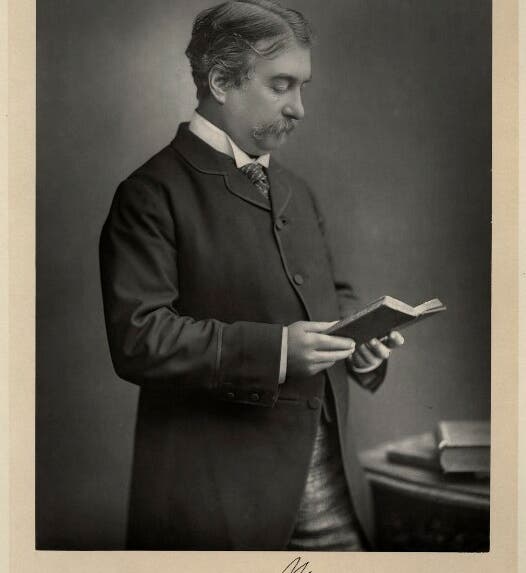

We just recently (last week) added to our collections the Life and Work of Sir Norman Lockyer (1928), edited by his widow Mary. Our copy contains a sheet of “Lady Lockyer’s” printed stationery, laid in, where she presents, in her own hand, this copy to an admirer, the astronomer Charles St. John. This book also includes a heliotype portrait of Lockyer, much more seasoned than he appears in the portrait we reproduce here, from the National Portrait Gallery (first image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.