Scientist of the Day - Milton Humason

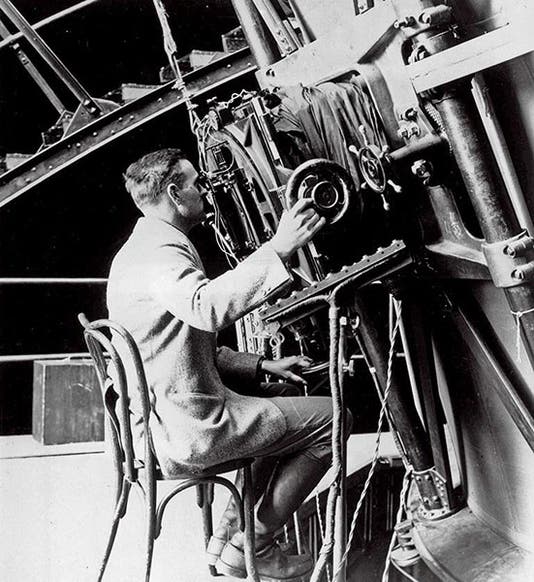

Milton Humason, an American astronomical technician, was born Aug. 19, 1891, in southern Minnesota. He spent a high-school summer in the Pasadena area of southern California and liked it so much that he never went home. Nor did he go back to school, preferring to work as a laborer on the many construction projects under way in Pasadena, including the building of a road up Mt. Wilson for a new observatory that was being established at the top. After hauling up supplies by mule for the buildings, Humason got a job as a custodian when the Mt. Wilson Observatory was opened and then moved up to a position as a night assistant. It turned out that Humason had a gift for instruments, and he was soon taking photographs with the new 100" Hooker telescope that opened in 1918. This was about the time that Edwin Hubble joined the staff at Mt. Wilson, with the project of trying to determine whether the Andromeda nebula is a cloud of gas or a galaxy of stars. To see stars in Andromeda, Hubble needed photographs with the highest resolution possible, and Humason provided these, which enabled Hubble to demonstrate without question that Andromeda is a galaxy of stars just like the Milky Way. We see in the first image Humason manipulating the 100” telescope in 1922. George Ellery Hale, the director of the Observatory (and the man who put this high-school dropout on his astronomical staff, to the disgruntlement of many of the more highly educated employees), then gave Humason the task of using a spectrograph to photographically record the spectra of nebulae. Spectroscopic photography was nearly 60 years old by this time, but the purpose of most spectroscopy was to allow one to identify the elements making up the planet, star, or nebula being observed. Hale had a different task in mind – he wanted Humason to determine whether the spectral lines were where they should be, or whether they might have shifted to the red end or the blue end of the spectrum. A blue shift indicates that the object is moving towards us; a red shift, that it is moving away. Vesto Slipher at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona had earlier (1915-17) examined the spectra of 25 of the brighter nebulae and had shown that 22 of them have red shifts, which was surprising. Humason tackled the more difficult dimmer nebulae (now known, after 1925, to be galaxies), and he found that ALL of them had red shifts, and the dimmer they were, the greater the red shift, indicating that they are moving away from us faster and faster. Edwin Hubble then determined the distances to the observed galaxies, matched them up with Humason's measured red shifts (recession velocities), and by 1929 had formulated Hubble's law, which states that there is a one-to-one relationship between distance and red shift. If a galaxy is twice as far away, it is moving away from us twice as fast. Others (not Hubble, and not Humason) would use Hubble's law as evidence that the universe is expanding, one of the great discoveries in 20th-century cosmology. Humason certainly played a major role in making that discovery possible.

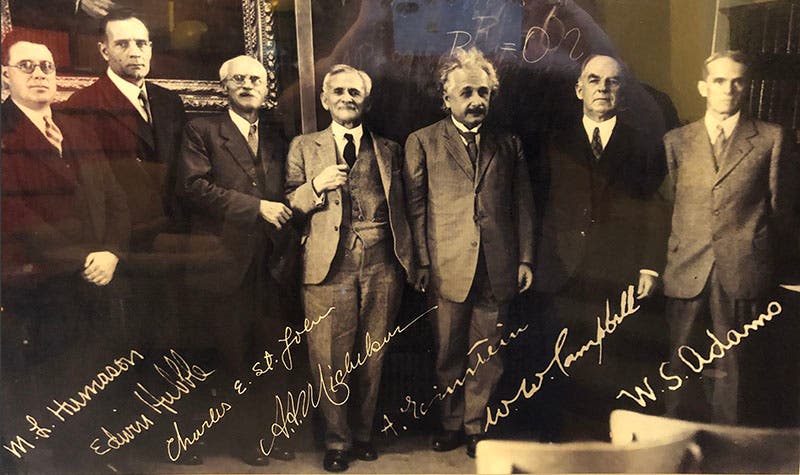

It has been a common practice among science journalists to make Humason into something he is not – to promote him as the high-school dropout and mule driver who rose by his own bootstraps to show the Cal Tech PhDs a thing or two about cosmology (with headlines like this one: “How a janitor at the Mount Wilson Observatory measured the size of the universe” from a Christian Science Monitor article in 2010). A photograph such as the one above – for all its charm – does not really disabuse that notion (that is Humason on the left, next to Hubble, with Einstein in the center). But anyone who really wants to comprehend what Humason did, and did not do, should read in full the transcript of the oral interview that Humason gave in 1965, when he was 74 years old. It reveals a modest and relatively uneducated man who knew what he was good at – tracking objects with a camera and measuring red shifts – but who left the interpretation and theory to others, and never pretended to be what he was not. Science needs the talents of both the Humasons and the Hubbles. But it is unwise to imagine that they are doing the same thing. I am guessing that the modest older Humason (see photograph) would have been a more agreeable dinner companion than the older not-so-modest Hubble. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.