Scientist of the Day - Maurits Escher

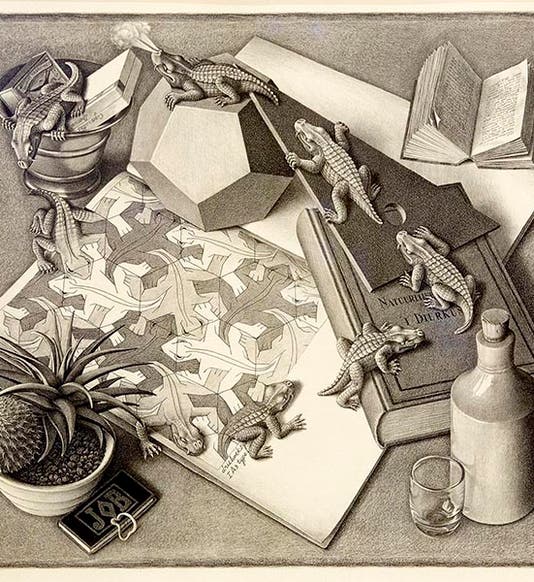

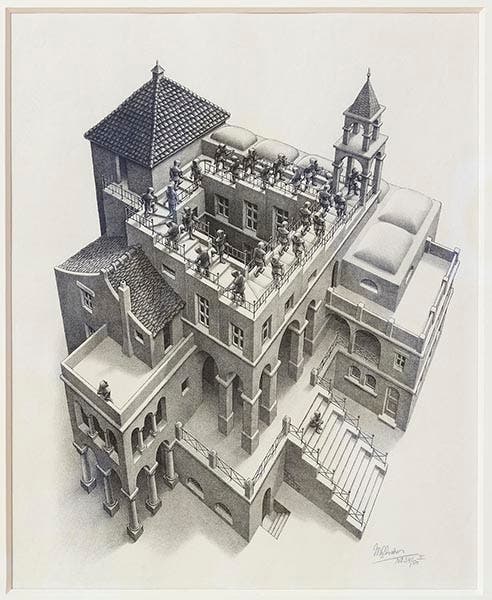

Maurits Cornelis Escher, a Dutch graphic artist, was born June 17, 1898. I am sure everyone has seen an Escher woodcut or lithograph at some point, perhaps one of his early tessellations, such as Day and Night (1938). Moving out from tessellations, Escher began to play with three-dimensional reality, as in the woodcut Reptiles (1943; first image), which is still one of my favorite Escher prints, and as time went on, his realities became paradoxical, as in Drawing Hands (1948), where each hand creates the other, and provides a visual counterpart to the Cretan who famously said, “All Cretans are liars.” Escher also liked to depict scenes that looked real enough but were quite impossible, as in Relativity (1953). Sometime in the mid-1950s, Escher's work came to the attention of a British mathematician, Roger Penrose, who was very fond of mathematical games, and Penrose thought he would have a go at creating an Escher-like impossible reality. With the help of his father, he came up with what we now call the Penrose steps, and in 1958, the two published a short paper in a psychology journal on their creation, which looks something like this. Professor Penrose then sent a copy of the paper to Escher, expressing his admiration for Escher's work, and Escher responded with a lithograph of his own, Ascending and Descending (1960; second image), which depicts a procession of identical figures going endlessly up (and down) a set of Penrose steps.

For the film Inception (2010), director Christopher Nolan thought a paradoxical staircase would be just right for his dream-sequence movie, and there is a short segment in the film that shows Joseph Gordon-Levitt and Ellen Page climbing a Penrose/Escher staircase. For some reason they chose to spoil the paradox at the end; it would have been much more effective had they just kept going until the dream bubble burst. I would like to link to one last visual, a video of a ball bouncing up an Escher/Penrose staircase with accompanying music, because not only does the ball go up forever, without ever reaching the top, but the music seems to go up in tone as well, and yet it too never gets any higher. This tonal sequence is called a Shepard scale, and on some future occasion, say the Jan. 30 birthday of cognitive scientist Roger Shepard, we might have more to say about this sequence of seemingly paradoxical tonalities. I do not know if Escher ever heard it (it is possible timewise); if so, I am sure he was, or would have been, delighted. Instead of a portrait, we show you an Escher lithograph of 1935, Hand with Reflecting Sphere, out of which peers the face of Escher himself. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.