Scientist of the Day - Mary Anning

Mary Anning, an English curio shop owner and fossil finder extraordinaire, was born May 21, 1799. Mary grew up on the Dorset coast of southern England, and as a child she would help her father and mother (Richard and Molly) find beach-side collectibles to sell in their shop in Lyme Regis. The coastal rocks at Lyme Regis are sedimentary slates, shales, and clays, now known to be of Jurassic age, and they are filled with fossils, especially ammonites, which erode out regularly. The ammonites were a popular item in the seaside tourist shops, and Mary and her older brother Joseph (the only two of nine children to survive) became adept at identifying and collecting good specimens.

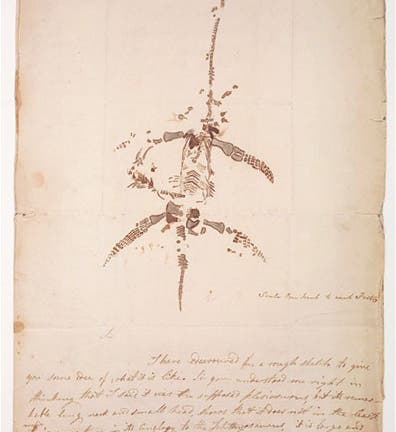

Richard died when Mary was only eleven years old, and Mary and Joseph now became the primary providers for the family. Fortunately, Mary had an amazing knack for finding fossils. In 1811, Joseph found the skull of a strange marine creature washed out of the cliffs. Mary, just 12 years old at the time, went looking for the rest of the remains and managed to locate many of the fossilized bones of a sea-going reptile with paddle-like limbs, which turned out to be the first Ichthyosaurus ever discovered. She found several more ichthyosaur specimens in the ensuing years, including a large one of 1818 that was nearly complete. In 1823, she discovered the world's first Plesiosaurus, quite a different kind of marine reptile, with a long neck and a turtle-shaped body, which is familiar to most of us as the designated denizen of the depths of Loch Ness. An autograph drawing she made of this specimen survives, along with an accompanying letter, in the Welcome Collection (first image). Finally, since we seem to be cataloguing firsts, Miss Anning dug out the first pterosaur ever found in England, a Dimorphodon, in 1828.

Although Mary was befriended by several notable naturalists, such as Henry de la Beche, William Conybeare, and Adam Sedgwick (who bought several of her finds), she generally got little or no credit for her discoveries during her lifetime, nor much money. When Everard Home wrote a paper on the first Ichthyosaurus specimen in 1814 for the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, he did not mention Mary Anning at all. He wrote two more such papers, including one on the large nearly complete specimen of 1818, with a lovely engraving, and he did not mention Mary there either. Everard Home, it turned out, was a scoundrel, but even those of more generous spirit, such as de la Beche and Conybeare, seldom went out of their way in their publications to call attention to the remarkable Miss Anning before her death.

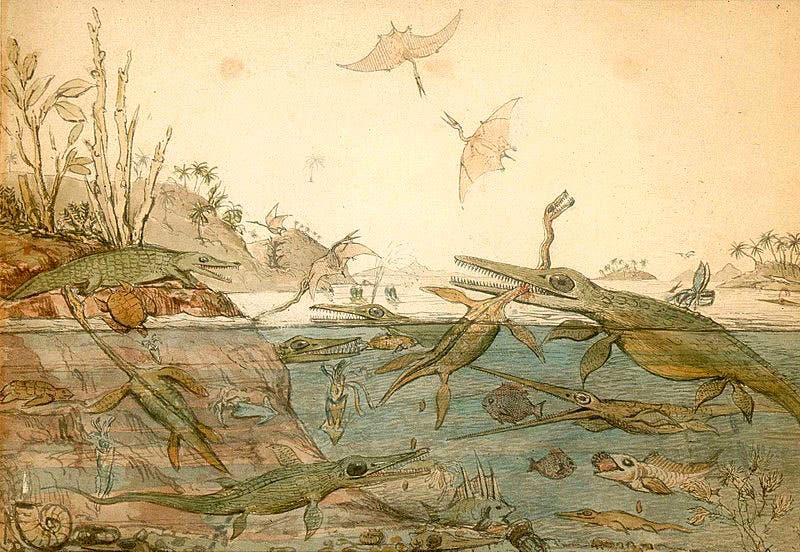

But to de la Beche’s credit, when Mary ran into financial difficulties in the late 1820s, he orchestrated a benefit on her behalf. A talented artist, de la Beche painted a prehistoric scene – really the first such scene – that attempted to recreate extinct lift forms in their ancient habitat. The watercolor is called Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset; second image). De la Beche then commissioned an engraving of his painting and sold the engravings, with the proceeds going to Mary Anning. The original painting is in the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff. Copies of the engraving can be found in various museums and libraries, although not, alas, in ours. We link you to one at the Geological Society of London.

Mary died in 1847 of breast cancer. Although she was little heralded in her lifetime, she has since grown to become an iconic woman scientist, perhaps – with Marie Curie – the most iconic. She is especially dear to the Natural History Museum in London, which has many of the specimens she found, including the first ichthyosaurus, plesiosaurus, and pterosaur.

We have all the original engravings and lithographs of Mary’s specimens, as they appeared in the various journals, in our Library, but we cannot get at them during the current crisis. Some years ago we did a post on Conybeare, who (with de la Beche) wrote the description of the first Plesiosaurus in 1824, and you can see there the engraving that was printed with that description. We have also done posts on de la Beche and Buckland, although without mention of Mary Anning.

Mary’s house and shop in Lyme Regis, which you can see here in a sketch made in 1842, was later torn down so that the Lyme Regis Museum could be built on the site. A blue plaque commemorates the house that gave way to the museum. The portrait (third image) was painted in 1842 and copied in 1847; the copy (shown here) is in the Natural History Museum, London.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.