Scientist of the Day - Marie Tharp

Marie Tharp, an American cartographer and geologist, was born July 30, 1920. After acquiring degrees in English, geology, and math, she went searching for an interesting career. After several unpromising starts, she was hired in 1948 by geophysicist “Doc” Ewing at Columbia University, and when in 1949, Ewing became the first director of the new Lamont Geological Laboratory (now the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory) at Columbia, she moved right along with him. She soon teamed up with Bruce Heezen, a slightly younger geologist, who spent much of his time cruising across the Atlantic Ocean in an oceanographic vessel, the Atlantis, taking soundings of the ocean floor. One cruise would yield one "profile", a collection of data giving the ocean depth for that particular track of the ship. When plotted, the profile data for one cruise would appear as a saw-tooth line, indicating the peaks and valleys of the sea floor for that cruise. Tharp's job was to transform the data into visual profiles, and then onto charts, slowly revealing the contours of the Atlantic Ocean floor.

It was late in 1952 that Tharp made her first big discovery. She noticed that on three of the North Atlantic profiles she had constructed, there was a V-shaped cleft in the middle, right where each profile crossed the top of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (this massive undersea mountain chain, which runs north-south through the Atlantic Ocean, had been discovered during WWII and was now being actively studied by geophysicists). It was as if there were a rift valley that ran along the top of the ridge. She showed this to Heezen, and one of them--recollections differ--compared Tharp’s chart of the rift with another chart being made at Lamont, at the same scale, of earthquakes recorded along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. It was found that nearly all the earthquakes occurred within the rift valley. Soon comparisons were made to the Great Rift Valley in East Africa, where one finds an identical geological situation, and for the first time it was realized that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge might be an East African rift valley on a colossal scale. This was in some ways the first step on the path that led to the discovery of sea-floor spreading, the proposal that new material from the mantle wells up along the Mid-Atlantic ridge and pushes the two sides apart, slowly widening the Atlantic Ocean floor. Sea-floor spreading in turn would be a central concept in the development of plate tectonics.

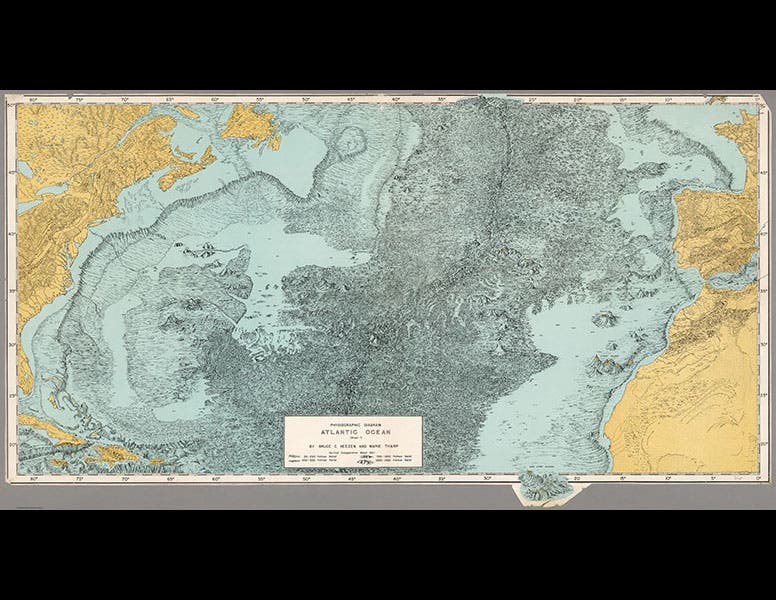

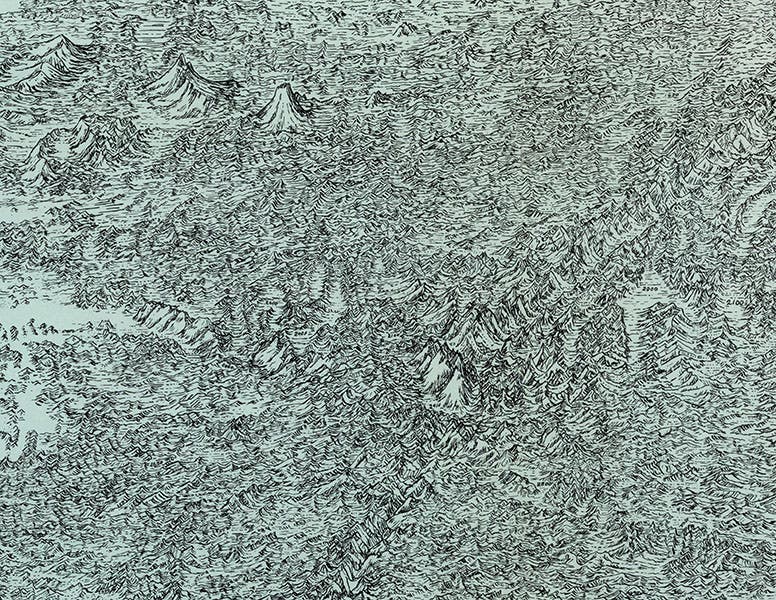

By 1957, Tharp had finished a map of the entire Atlantic Ocean floor, the first ever, and the mid-Atlantic ridge, with its central rift valley, stood out prominently. We see three photos of this map above; one on a table for scale, one showing the entire map, and one providing a detail of the central portion of the map and the mid-Atlantic ridge (third image). A fourth photo (fourth image) shows Marie working on the map (OK, she is posing with the map), and one can see, propped up in the back, a chart with the first six profiles that she compiled in 1952, the ones that first showed the existence of the rift valley.

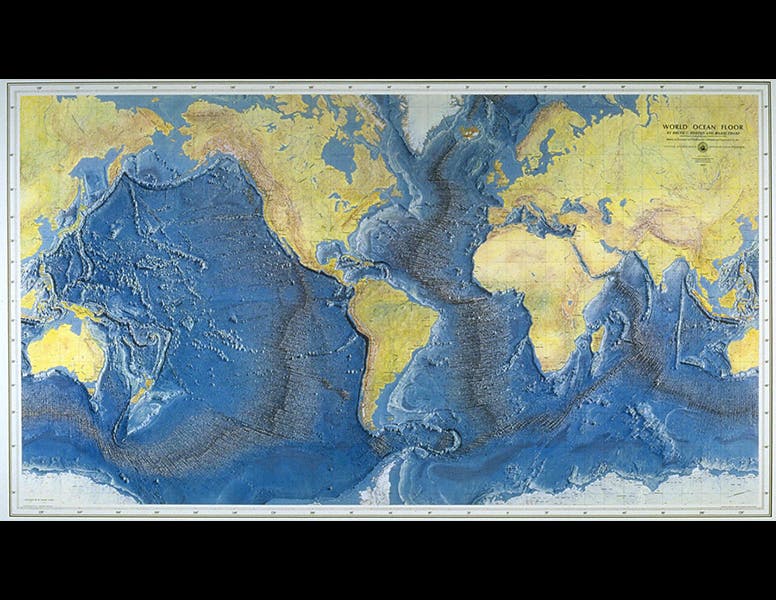

Tharp continued to work with Heezen for the rest of his life (he died in 1977 of a heart attack while in a submersible in the mid-Atlantic), even when Heezen and Ewing had a massive falling out and Heezen was forbidden to use any Lamont ships or have access to any Lamont data. Nevertheless, by 1977, Tharp and Heezen (fifth image) finally completed a map of the ocean floor of the entire earth, which clearly shows the extent of the oceanic ridges that snake through the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans (sixth image). This map, a beautiful and meticulous piece of cartography, is a wonderful testament to Tharp’s life’s work, and a sad memorial to Heezen, who died just before it was released.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.