Scientist of the Day - Margaret Harwood

Margaret Harwood, born on Mar. 19, 1885 in Littleton, Massachusetts, became the first woman – and for a long time the only woman – to serve as director of an independent astronomical observatory. She took charge of the Maria Mitchell Observatory on Nantucket Island in 1916, and remained in that post for forty-one years.

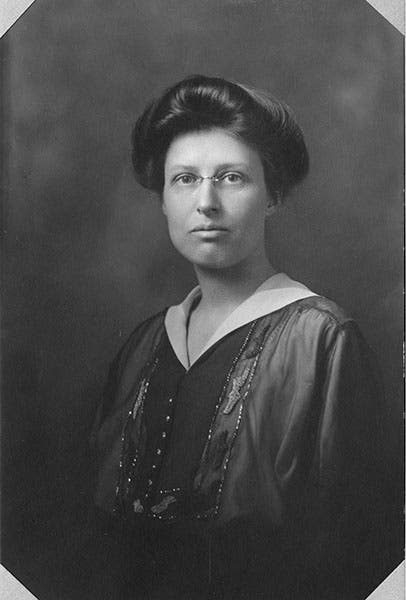

Miss Harwood had planned to study physics, chemistry and math when she entered Radcliffe College in 1903, but her choice of lodgings turned her to astronomy. She boarded with the family of Arthur Searle, a genial fixture at the Harvard College Observatory. Soon she was trailing him up Observatory Hill, learning to use the telescopes, earning the friendship and mentoring of other staff members, from Edward Pickering to Annie Jump Cannon and Henrietta Leavitt. By the time of Miss Harwood’s graduation (second image), she was ready to step into a paid position as an assistant. The position didn’t pay much, however, and she supplemented her income of about $500 per year by teaching science in the mornings at a couple of local schools.

In 1912, the Maria Mitchell Association awarded Miss Harwood a new fellowship in astronomy worth $1,000. It came with a new opportunity: From June to December of that year, she took up residence in the old Mitchell homestead on Nantucket, where she curated a small museum and library, used the telescope in the next-door dome to further her own research on asteroids, and lectured on astronomy to the locals every Monday night.

Although the fellowship was meant to bring a new female astronomer to the island each year, Miss Harwood made such a success of the position that she was invited back for 1913 and again in 1914. She spent the other six months of those years at the Harvard observatory (third image). In 1915, the Association again tendered her the $1,000 stipend, but left her time free to do as she pleased. She chose to travel cross country to the Lick Observatory, to continue tracking asteroids and variable stars while working toward her master’s degree in astronomy at the University of California, Berkeley. While en route west, she received an offer from Wellesley College to begin teaching astronomy there upon completion of her graduate studies. But the Maria Mitchell Association, keen to keep her and see her continue her own research, matched the Wellesley salary and made her director of the Nantucket observatory (fourth image). She was only thirty years old.

The close connection between the two observatories brought a series of guest speakers from Harvard to Nantucket. Miss Harwood, as the link between the two, was in the best position to suggest lecture topics. She once counseled Harlow Shapley against a proposed talk on navigation because, she said, the island population had proprietary feelings about “everything connected with the sea.” Some years prior, she continued, “a man came to lecture on whales. Many of the old inhabitants, including sea captains, went expecting to hear a description of Wales. And when the lecturer began to explain the anatomy of the whale, the old whalers ‘talked-back,’ made much fun, and there was a general rumpus.”

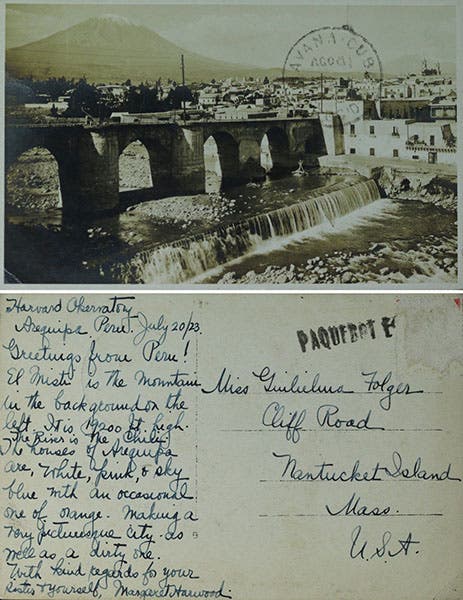

Postcard sent by Margaret Harwood from the Harvard Station at Arequipa, Peru, 1923 (photos by Caroline Freeman)

Shapley, who assumed the directorship at Harvard after Pickering’s death, was extremely fond of Miss Harwood, and addressed her as Marnie in his letters. She, in turn, collected ants for his sideline entomology studies. She sent him a few specimens from Arequipa, Peru, while observing at the Harvard station there in 1923 (fifth image), and several more later that same year from Pasadena, where she had hoped to witness the September 10 total solar eclipse. Her group included Edwin Hubble, but clouds and storms obscured the event all across southern California. “All was dead silence,” she wrote home in the aftermath, “excepting Mr. Hubble’s voice counting the seconds over behind the huge metal framework that held 15 different telescopic cameras and spectrographs for making 15 different kinds of observations.” She had better luck two years later, when she witnessed the January 24, 1925 total solar eclipse right at home on Nantucket, together with Cecilia Payne and Edward King of the Harvard observatory.

Miss Harwood belonged to numerous professional and amateur organizations of stargazers, including the American Association of Variable Star Observers (sixth image), and the International Astronomical Union. Active with the Home Service of the American Red Cross after the first World War, Miss Harwood spent the Second World War years teaching navigation techniques for the U.S. Coast Guard.

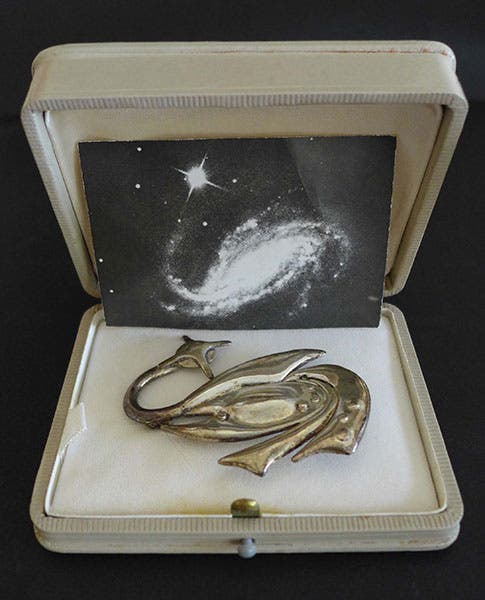

In 1957, with considerable reluctance, Miss Harwood retired from her post at Nantucket. In 1961 she accepted the Annie Jump Cannon Prize, which had been established by its namesake in the 1930s, and first conferred on Cecilia Payne. The prize is still awarded today by the American Astronomical Society to a young woman at the start of her career, but it no longer comes with a custom-designed piece of astronomically themed jewelry (seventh image). Instead, the winner is invited to lecture about her research at the Society’s annual meeting. No doubt Miss Harwood would approve.

Dava Sobel is the author of Longitude, Galileo’s Daughter, and, most recently, The Glass Universe. She edits a new poetry column, called “Meter,” for Scientific American.

![Using an astrolabe to measure the depth of a well, woodcut in Elucidatio fabricae vsusq[ue] astrolabii, by Johannes Stöffler, 1513 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/a998eb50-55d2-4a88-ace2-a50aa5fa86e7/Stoffler%201.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)