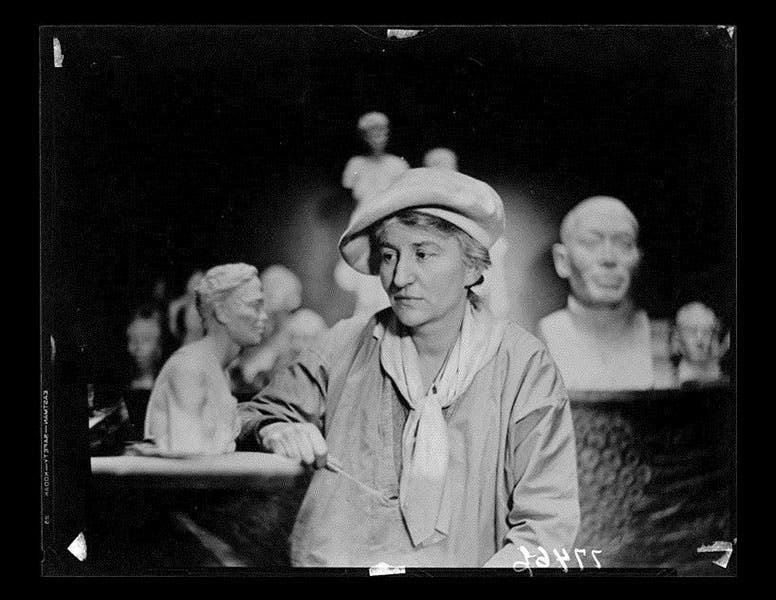

Scientist of the Day - Malvina Hoffman

Malvina Hoffman, an American sculptor, was born June 15, 1885. In 1929, Hoffman was asked by Stanley Field, the director of the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, if she would be interested in creating sculptures depicting the various "racial types" of the human species. As proposed, this was to be a group project, involving many sculptors, but Hoffman agreed only if she could create all the sculptures herself. She also insisted that they be bronze, not plaster. Her counter-proposal was accepted, and she got to work. Hoffman used livings models for all her sculptures, starting with the Colonial Exposition in Paris in 1930, when peoples from all over the world were gathered together, and then travelling herself to remote locations to seek out human types not yet represented. Three years later, she had completed 104 sculptures - life-size statues, busts, and heads – and they were installed in the Museum's Anthropology Hall as a permanent exhibition, The Races of Mankind.

The exhibit was quite popular at the Museum for the next few decades, but by the time of Hoffman's death in 1966, "racial types" had become a troublesome concept. If was becoming more and more clear to scientists that the idea of race was not based on any biological parameters, and that race is really a social construct, not a physical one. The Races of Mankind became an embarrassment, and it was uninstalled and put in storage.

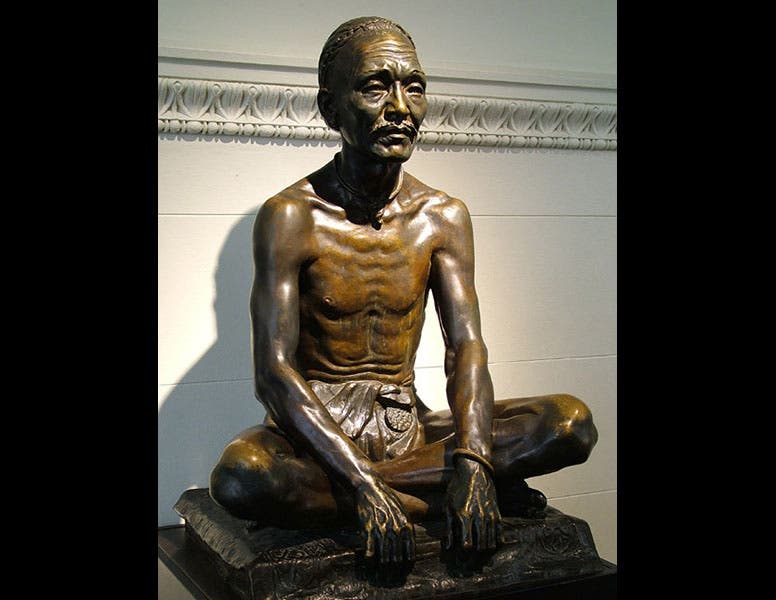

Lost in all this was the fact that Hoffman's sculptures were not at all racial, in the derogatory sense of the word. Each bronze figure had a great deal of dignity, one might even say aspiration, and each was beautifully portrayed. Were one to retitle the exhibition, “The Variety of Human Experience”, or “The Nature of Being Human”, there would be nothing embarrassing about it. The Field Museum, to its great credit, came to realize this, and in 2016, they reinstalled 50 of the sculptures under a new banner: Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman . The exhibition will be on display until Feb. 3, 2019, and one hopes that, if response is favorable, a little bit longer than that.

The images above show six of Hoffman’s sculptures, a portrait of Hoffman, and a period photo that depicts Field, Hoffman, and two of her bronzes as they were being installed in 1933.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.