Scientist of the Day - Maarten Schmidt

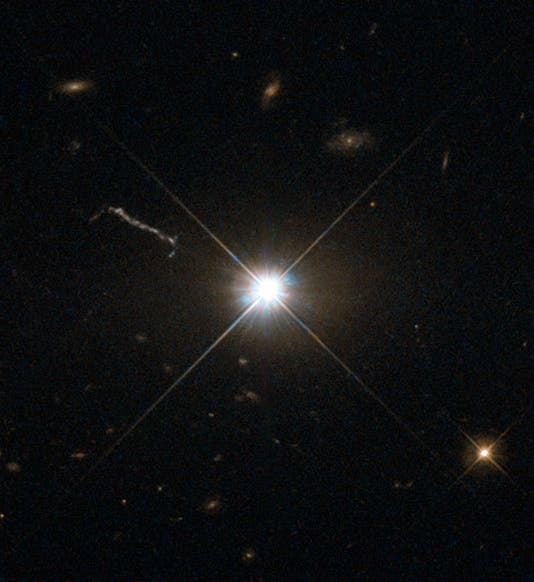

Maarten Schmidt, a Dutch/American astronomer, was born Dec. 28, 1929. In 1960, a new kind of deep-space object, known as a quasar, was discovered. Quasars are intense sources of radio energy, yet they are barely perceptible as points of light, hence the name: QUASi-stellAR radio source. The first photo above shows 3C 273, the quasar that Schmidt would make famous, as viewed by the Hubble Space Telescope, but to most other viewers it is a quite undistinguished object, as you can see in the wide-field photograph above (second image), where it is the dot just to the right of the “3” in the 3C 273 label.

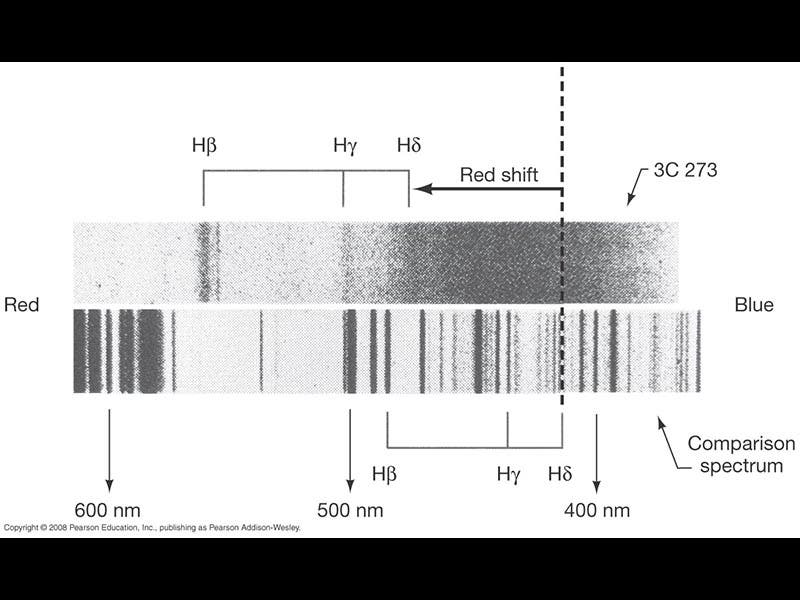

Quasars like 3C 273 were mysterious because they had an unrecognizable spectrum. When you spread out the light from most star-like objects, one sees three prominent spectral lines due to hydrogen, but the lines from quasars did not conform to the standard pattern, and no one could figure them out. Until Schmidt, on Feb. 6, 1963, truly saw the light. He was pondering the spectrum of 3C 273, when he wondered: what if the spectrum had been drastically red-shifted, so that the visible lines are those that, in most light sources, are actually invisible in the ultraviolet region? He rapidly did some calculations and realized that if you took ordinary light and shifted it to the red by a factor of 16%, you would produce the exact spectrum of 3C 273 (you can see the actual spectrum of 3C 273 above (third image), with a comparison spectrum below, and the hydrogen spectral lines labelled and shifted). And because of Hubble’s law that equates red shift with recession velocity, this means that 3C 273 is moving away from us at 16% the speed of light, or about 30,000 miles a second, the fastest moving object ever recorded to that time. And it further means that 3C 273 is over 2 billion light years away, making it the most distant object in the universe detected up to that time.

Quasars were still a mystery after Schmidt’s discovery, since, to be visible at all from that distance, they must be incredibly powerful, giving off the energy of entire galaxies in a very small volume. But at least we now knew where they are, and, more importantly, when they were--creatures of the early days of the universe, whose light is only now reaching us.

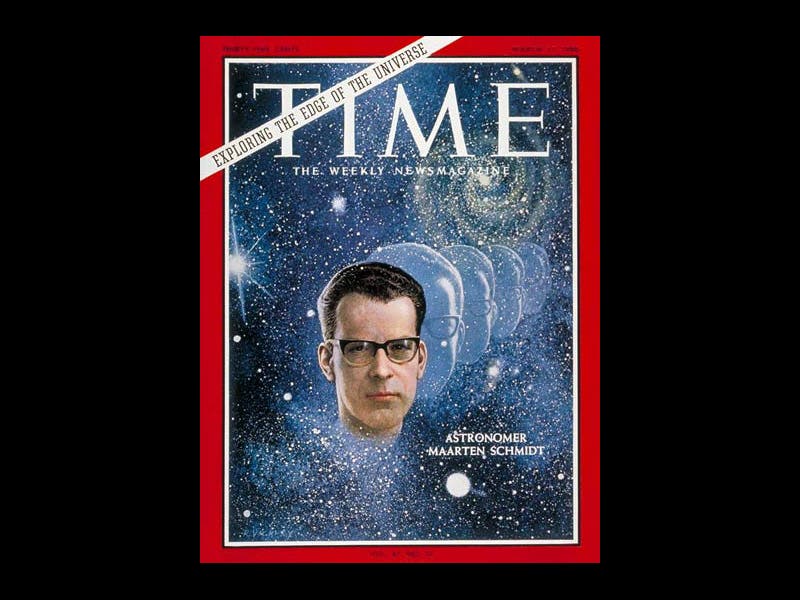

Schmidt is 87 years old today. He should have been awarded a Nobel Prize for his discovery, but since there is no Nobel Prize for astronomy, he has had to settle, like all high-achieving astronomers, for being on the cover of Time Magazine in 1966 (fourth image), and for the Bruce Medal, which he received in 1992.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.