Scientist of the Day - Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci, Renaissance man incarnate, was born Apr. 15, 1452. Surprisingly, we have never written a post on Leonardo, so this is the first of what will certainly be a series, since no one could treat the many aspects of his varied career in one essay. We begin with some of his inventions-on-paper, since, to me, they epitomize Leonardo’s unique ability to think far outside the box and then record his ideas in wonderful drawings, made possible by his exquisite draftsmanship. Leonardo made notes and drawings all his life, on sheets of paper that were, much later, bound up into notebooks. The largest collection is the Codex Atlanticus, put into its present form in the late 16th-century by Pompeo Leoni and now (after a short stay in Napoleonic Paris) residing in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan. It was issued in sumptuous facsimile in 12 large folio volumes in 1973, and we have a set of the facsimiles in our History of Science Collection. The other set of drawings we will draw upon is the Codices Madrid, two small volumes which long lay hidden in Spain until their rediscovery in 1965. They are filled with technical drawings and were issued in facsimile in 1974. We have this as well in the Library.

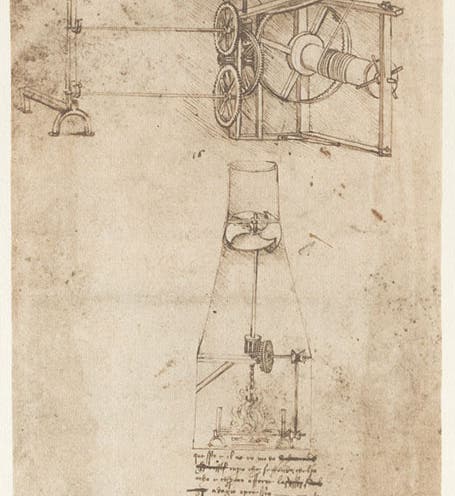

One can look at these notebook pages from various points of view. Many have sifted through them for inventions that would only be realized centuries later, such as flying machines, parachutes, tanks, and the like. I am going to take a different tack and select several drawings of more humdrum objects that I like because they show how Leonardo was able to look at a mechanical problem and discover all the possible solutions, almost at once, and then hone the best one to perfection. For example, our first example (first image at top) has two drawings of mechanical spits, for turning meat being cooked over a fire. The top drawing, beautiful though it is, shows a fairly conventional mechanism, using a falling weight to turn a series of gears that rotate the two spits at the left. But the bottom drawing is much more ingenious. Here the spit is turned by a turbine blade up in the flue. As Leonardo points out in the text below, as the fire gets hotter, the fan blade will rotate faster and turn the spit faster, which is just what is needed to prevent the meat from burning over the hotter fire. The text, incidentally, is written in Leonardo's own hand in right-to-left Italian. That's just the way Leonardo took notes, and you need either a mirror or long practice to read it.

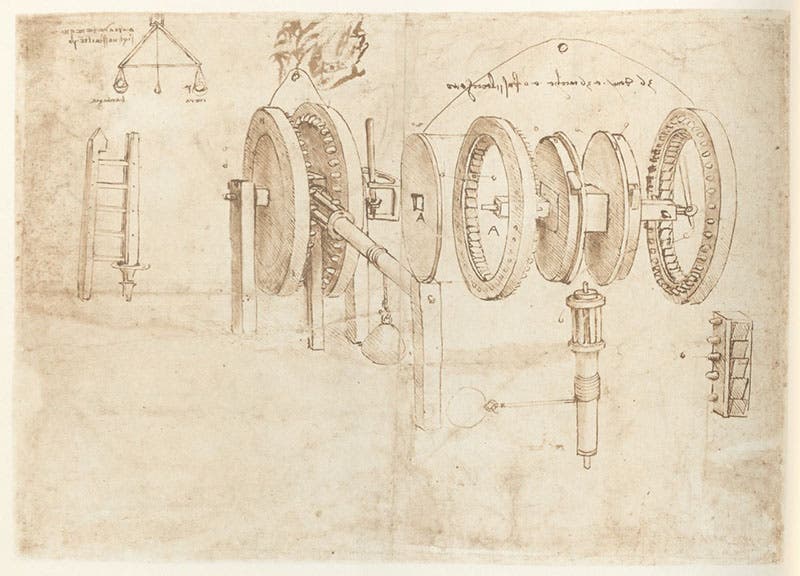

Our second drawing (third image, just above) is significant not so much for the actual invention, a device to raise a weight with a ratchet-like mechanism, as it is for the way the mechanism is drawn. We see the intact mechanism at the left. On the right, Leonardo blows it apart with his pencil, so that we can see the internal parts of the mechanism - the wheels with pegs and the ratchet pawls and the shaft that rotates and lifts the weight. We would now call such a sketch an "exploded diagram," and it is a commonplace in modern engineering drawing. It was not a commonplace in 1478, when this drawing was made. To the best of my knowledge, Leonardo invented the exploded diagram, right here.

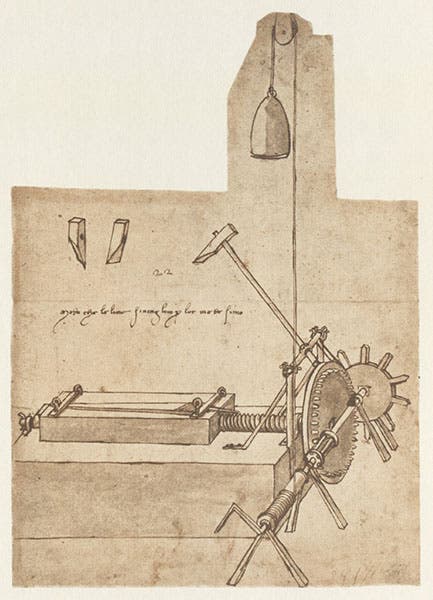

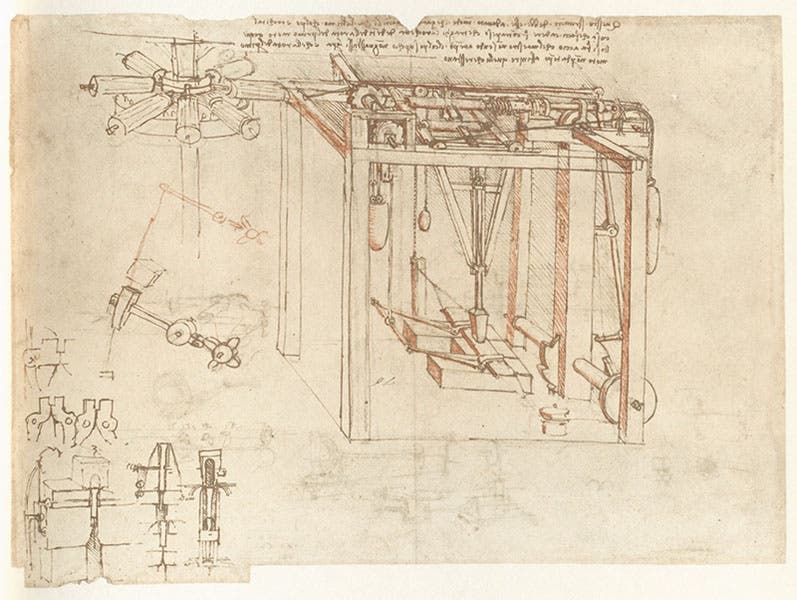

Our third example (fourth image, just above) is my favorite Leonardo invention of all, a file-making machine, a choice that used to amuse my students, who much preferred helicopters and mega-crossbows. I like this one because it demonstrates better than any other example I have found, how Leonardo could look at an existing way of doing things, see at once how the various steps could be converted to machine language, and then come up with a device for doing the same task faster, better, and cheaper. In medieval times, you made a file in the following manner: you had a blacksmith forge a blank of wrought iron. Then you used a chisel and mallet to make a groove in the blank. You moved the chisel a sixteenth of an inch, hit it again with the mallet, and made another grove. You continued this way until there were a hundred or so parallel grooves on one side, then you turned it over and went through the same process on the other side, and your file was done. It was only as good as you were able to maintain equal spacing with the chisel and equal force of striking with the mallet. It would probably take you the better part of a morning and leave you with a sore arm and numerous cuts on your hands.

Leonardo automated everything except the input of power. The file blank in his device sits on a bed connected to a screw drive. The chisel is mounted on an arm that is raised by turning the crank perhaps half a dozen times; the arm is connected to a weight. At a certain point, the arm trips and the chisel falls to make a groove in the blank. You continue to turn the crank to raise the chisel again, and meanwhile the screw drive advances the file bed a sixteenth of an inch, so that when the chisel falls the next time, the next groove is one/sixteenth of an inch from the first one. Turn the crank 600 times and you will have 100 evenly-space grooves on what is no longer a blank, but a file. If it takes five seconds to trip the chisel once, then the first half of the file would be finished in about ten minutes, and the back side in ten minutes more. That is, if you built such a machine. Leonardo never did. We have no evidence that he built any of his machine designs.

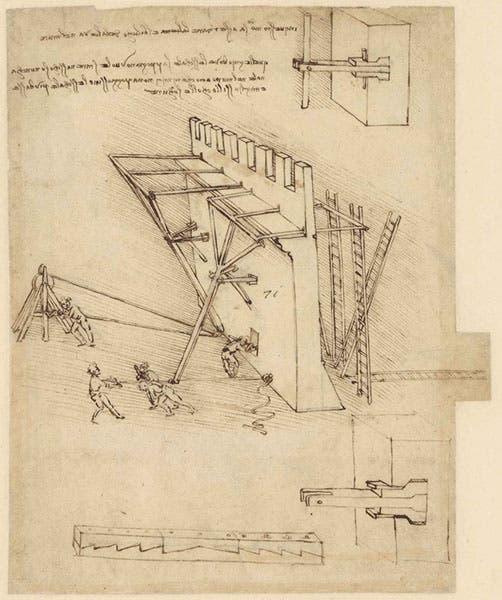

We do not have the space to discuss in detail the other drawings I selected, so I will just show them with the briefest of comments. Our fifth image (above) is a design for a device to repel invaders trying to scale a wall with ladders. Next is a machine for making gold foil; I have no idea how it works, but it is impressively complex and beautifully drawn (sixth image, just below)

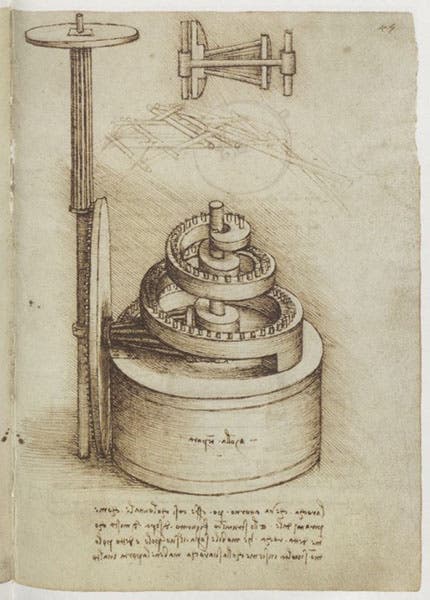

Our next two images form a pair, and in spite of what I just said, I have to comment just a little. The first is a device for drawing constant force from a tempered coiled steel spring, concealed in the drum at the bottom (seventh image, just below). As a spring unwinds, it loses power, and if you want to drive something like a clock, you need to compensate for the diminishing force. Leonardo does so by using a gear train that follows an inward turning spiral.

Some time later, Leonardo found an every more ingenious way to adjust the gear train, by using a helical drive train, which requires the driving gear at the left to slide up (eighth image, just above). Even if you cannot quite figure out exactly how either mechanism moves, you cannot help but admire the beautiful drawings, both of which can be found in the Madrid Codices.

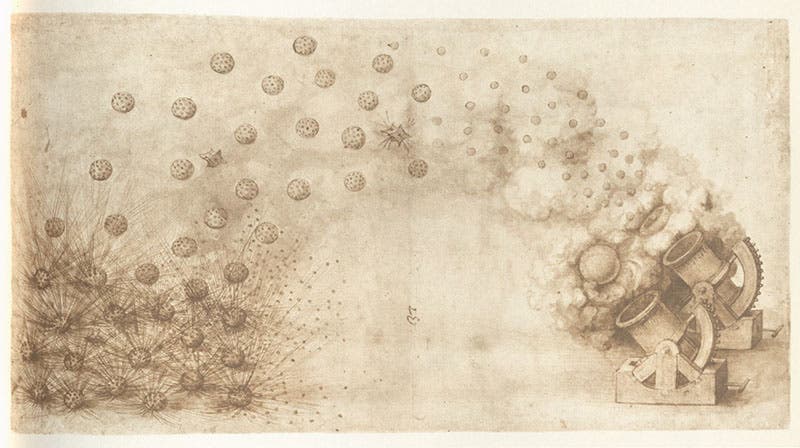

The final drawing of Leonardo that we show depicts mortars firing mortar bombs. Seldom have deadly instruments of war been rendered more beautifully than here.

In our next installment, we will look a little more at Leonardo’s life, and his work in anatomy, which was truly revolutionary, or would have been, had he published any of his drawings and observations.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.