Scientist of the Day - Lady Jane Franklin

Lady Jane Franklin, an English social activist and philanthropist, was born Dec. 4, 1791. Née Jane Griffin, she married, in 1828, the widowed Arctic explorer, John Franklin. When he was knighted the next year, she became Lady Jane. After a tour with the Mediterranean fleet, and with his proposal for another Arctic expedition rejected, Sir John accepted an appointment as Lieutenant Governor of Van Dieman's Land, now Tasmania, and Lady Jane found herself in the capacity of first lady to a foreign country. She accepted the responsibilities with enthusiasm, travelling throughout the land, making journeys no European woman had ever dared to make, and taking up the cause of the women convicts who made up a large share of the female component of the population. She seems to have been popular with everyone and highly respected, and was usually described in such terms as “vivacious”, “charming”, “dynamic”, and “persuasive”.

When Sir John was recalled under shabby circumstances in 1843, and when he heard that John Barrow, the man in the Admiralty in charge of polar exploration, was planning another search for a Northwest passage, he lobbied hard for the command, and got it. HMS Erebus and Terror and 129 crewmen set out from the Thames in May 1845 with great fanfare, but they were never to be seen again by any of their countrymen. After two years without word, Lady Jane took the reins and began petitioning the Admiralty to mount search expeditions. The earliest one, commanded by James Clark Ross, hero of the Antarctic, was sent out in 1848, and it was just the first of some 40 expeditions that would scour land, ice, and seas, in vain for 11 years. Many of the searches were in Royal Navy ships under Admiralty orders, but six were in ships owned or financed by Lady Franklin, using commanders and crews chosen and reimbursed by her. She even wrote to the U.S. President and a wealthy American friend, Henry Grinnell, asking for their aid, and they responded by sending out two ships owned by Grinnell and manned by the U.S. Navy.

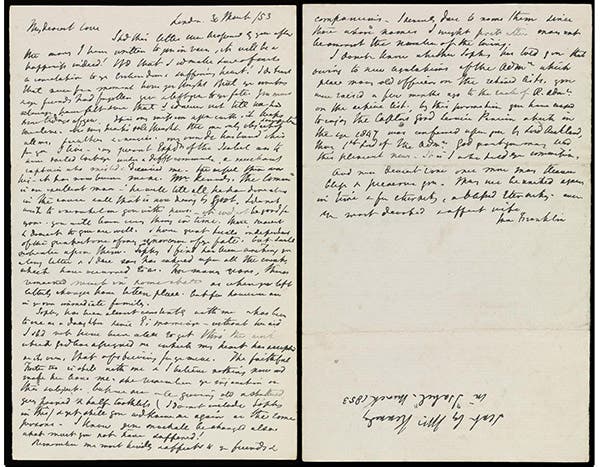

Lady Franklin also sent letters regularly to her husband, full of love and hope and good cheer, and she did this for years and years, with never a one delivered. You can see one of those, written in 1853 and now in the National Maritime Museum, in our fourth image.

The Royal Navy abandoned the search in 1855, after John Rae, the overland explorer, brought back artefacts from the Franklin ships acquired from local Inuit, as well as tales of men dying while attempting to trek south, and even accounts of evidence of cannibalism. The cannibalism accusation outraged Lady Franklin – Englishmen did not do such things, not under John Franklin's watch – and she acquired one more ship, a luxury yacht, the Fox, which she refitted and sent out with the veteran Arctic explorer and master of the sledge, Francis McClintock. It was this expedition that finally found a cairn with a document attesting that the Erebus and Terror had been abandoned, the men now on foot, and that John Franklin had died on June 11, 1847. Lady Jane could rest easier, now that Sir John was at rest.

Now Lady Jane devoted her time to ensuring that the members of the lost expedition were seen as heroes, and in that, she was largely successful. She also financed a statue of Sir John in London, and a memorial plaque in Westminster Abbey (sixth image).

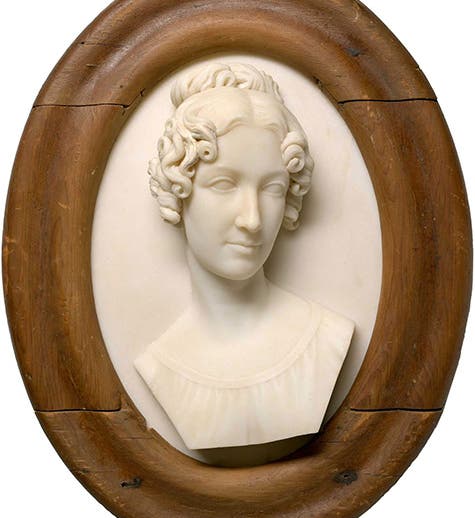

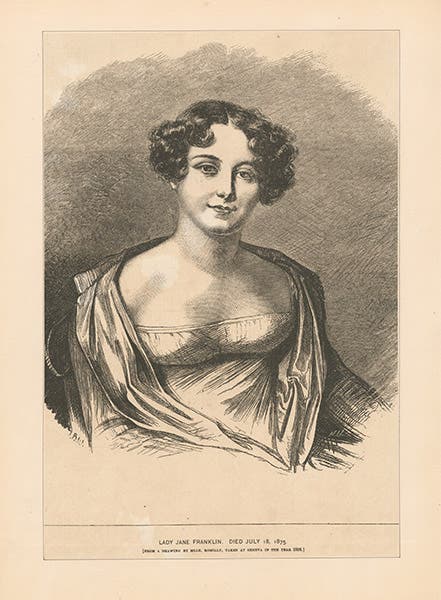

Lady Franklin is one of the great heroes of the "Search for Franklin" saga, even though her only role was to inspire and support others. It is odd that there seem to be only two surviving portraits, both sketches made when she was young (third image), and a sculpted relief that is not much a likeness (first image). The dawning age of photography failed to include her, sadly. Fortunately, most of her letters, and all of her diaries survive.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.