Scientist of the Day - Kurt Vonnegut, Jr

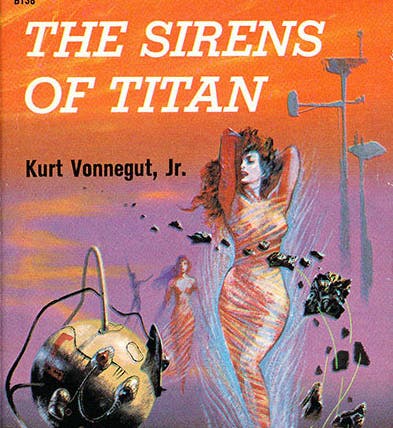

Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., an American writer, was born Nov. 11, 1922. Vonnegut is best known for an anti-war novel, Slaughterhouse Five, which brought him national fame and attention in 1969. But earlier he had written two science fiction novels, and it is these that attract our attention today. The Sirens of Titan appeared in 1959 as a paperback original, with a wonderful pulp-inspired cover (first image). I am sure that people who customarily bought books with this kind of cover were not at all prepared for what they encountered within. The principal character is an interplanetary entrepreneur, Winston Niles Rumford, who has become trapped, with his dog Kazak, in a chrono-synclastic infundibulum, a kind of worm-hole. He and Kazak pass by earth irregularly and materialize only on Titan, the large moon of Saturn. On Titan, Winston encounters Salo, a robot from the planet Trafalmadore in the Small Magellanic Cloud, whose spaceship has died and who is waiting for a spare part. Salo has been waiting for 200,000 years since he radioed home for help. I hope I don't spoil the book for anyone, but the upshot is that the Trafalmadorians had decided that the quickest way to repair Salo's ship was to evolve intelligent life on Earth, have them make the part, and then deliver it, which Winston arranges. The whole purpose of human existence, it seems, was to provide a simple piece of metal to a transient android. These were not exactly the lofty sentiments of 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was more like The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, only more sardonic, and 20 years earlier.

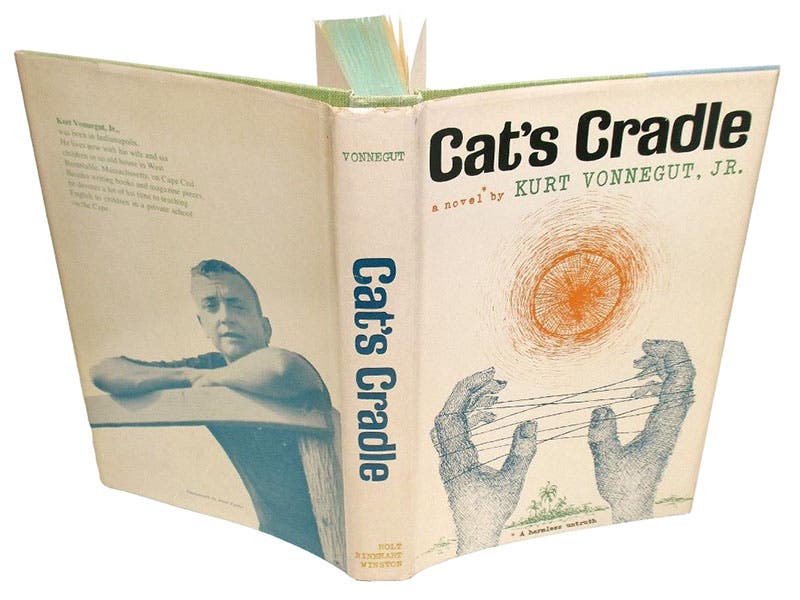

Vonnegut's other book-length foray into science fiction was Cat's Cradle, published in 1963. Cat's Cradle was issued in hardcover, and the dust jacket wasn't nearly as enticing as that of its predecessor (second image). The principal scientist in the book and the instigator of the plot is Dr. Felix Hoenikker, a Nobel laureate who invents a form of water called ice-nine, a seed of which will turn water into ice at room temperature, in an uncontrollable reaction. In a typical Vonnegut plot device, Felix bequeaths ice-nine to his children, thereby giving them the power to end the world. Ice-nine is a thinly veiled allegorical place-holder for the atomic bomb, which was conceived, in Vonnegut's opinion, by people who gave no thought to its dangers, and was now in the hands of idiots. I will leave you to discover on your own how the plot unfolds.

Vonnegut manages to be dark, acerbic, witty, and insightful, all at the same time. There is a point in Cat’s Cradle where the narrator, referring to a religion called Bokononism that plays a prominent role in the novel, points out that humans are social animals and like to belong to groups, but there are two kinds of human associations. The only true association is a karass, a sort of cosmic connection of individuals who are destined to interact in mysterious ways, even though the members may be completely unaware of the existence of the karass. All other associations are what Vonnegut's narrator calls granfalloons – coincidental associations utterly devoid of meaning, but which humans take quite seriously and treat as meaningful. Subsequently, the narrator is flying to San Lorenzo, the home of Bokononism, and a woman fellow passenger discovers that they are both from Indiana. “We are both Hoosiers,” cries the woman in delight (I write from memory here). “Granfalloon,” responds the narrator. To this day I cannot overhear two people expostulating over some new-found supposed kinship without saying: “Hoosiers!,” followed almost immediately by “granfalloon!”

Vonnegut also had considerable talent as an artist, and several years ago there was an exhibition of about 30 of his drawings at Cornell University. His graphics were just as pithy as his prose. You can see several of them at the exhibition website. The exhibition was titled, drawing on an oft-repeated mantra from Cat’s Cradle, “So it Goes.”

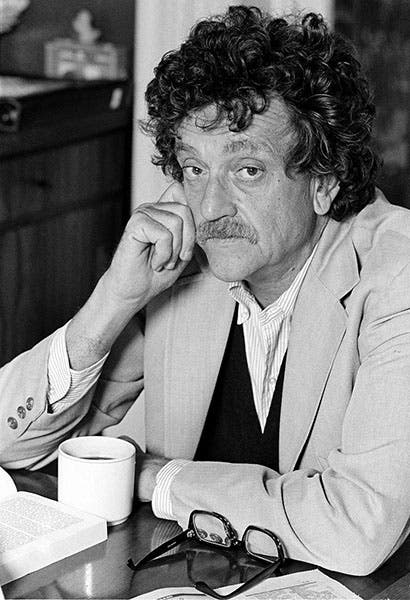

There is a photo of a 1962 clean-shaven Vonnegut on the back jacket of Cat’s Cradle (second image), but later in life he always sported an unruly mane and mustache, as in the 1979 photograph above (third image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.