Scientist of the Day - Karl von Frisch

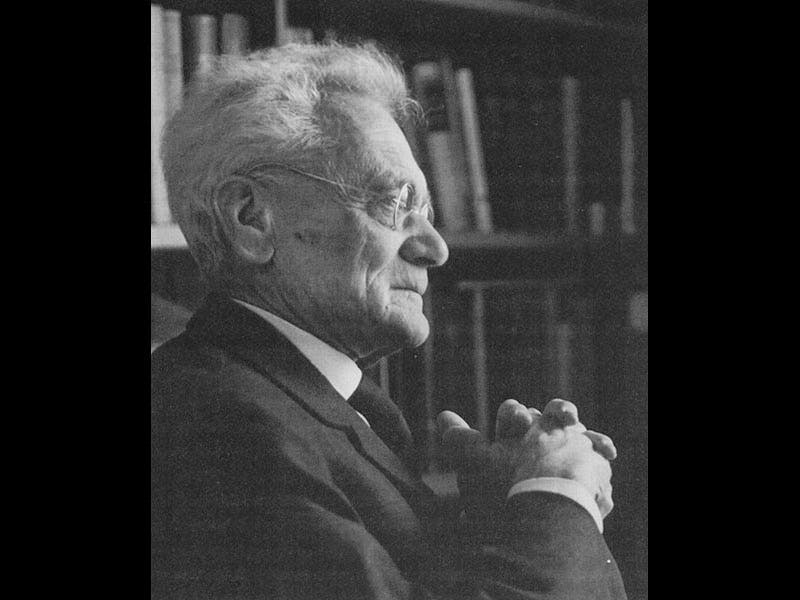

Thirty-five years ago today, Karl von Frisch died in Munich at the age of 95. Born in 1886 in Vienna, he would go on to have a remarkably productive career as an experimental physiologist who became known throughout the world for his discovery of the honeybee dance language (first image). In 1973, he won a share of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together with Niko Tinbergen and Konrad Lorenz. Together, the three were hailed as pioneers of the study of animal behavior known as ethology.

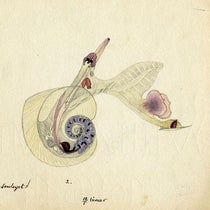

Through a series of elegant experiments that spanned several decades, Karl von Frisch showed that bees communicate the distance and direction of food sources via their figure-eight waggle dances. Others going as far back as Aristotle had commented on the bees’ curious movements in the hive, and bee keepers had long speculated about the insects’ abilities to communicate with each other to manage the complexities of the hive. But von Frisch was the first to put these phenomena together. He argued that the speed of the dances correlates with distance – the closer a food source, the faster the bees dance – and that the angle of her waggle runs in the hive corresponds to the angle she made with respect to the sun when she flew to the food. At the bottom of this website is a helpful image that explains this feature of the waggle dance (second image). The discovery was widely hailed as one of the most significant scientific findings in the post-war period. Not only biologists, but linguists, anthropologists, social scientists, and many others commented on the remarkable abilities of the bees to communicate. Today, the waggle dance of the bees still graces biology textbooks and the work continues to be cited, even though it’s over fifty years old.

But despite the relative acclaim the work has earned, I would like to share with you three aspects of von Frisch’s life and work that are less well known. And if you’ve never heard of von Frisch, not to worry – you may soon consider yourself an expert in advanced Frischiana (third image).

First, von Frisch actually discovered the dance language of the honeybees twice! The first time he argued that the bees dance a round dance to communicate the presence of nectar to hive mates, while the waggle dance communicates pollen. He wrote a small book on these discoveries in 1923, titled Über die “Sprache” der Bienen: eine Tierpsychologische Untersuchung (On the Language of Bees: A comparative-psychological examination). It’s a lovely book that’s still widely held at Library’s throughout the world. The only problem was that the theory von Frisch proposed in the book later proved incorrect. When he later discovered the second (and his final) version of the honeybee dance language, he was in the unenviable position of having to recant his earlier version – a unpalatable episode that niggled at him for the rest of his life. But if you’re curious to see version 1.0 of the honeybee dance language, you can consult a copy in KU’s library in Lawrence.

Second, although von Frisch has become synonymous with his favored research organism – the honeybee – he also worked on fish throughout his career, especially in the winter months when it was too cold for the bees to leave the hive (fourth image). But no matter how much he tried to promote his fish work, it was the bees that captured the public’s imagination. In the state library in Munich, where von Frisch’s personal and professional correspondence are held, a back-and-forth with a local teacher is captured. The teacher invited him to return to his school to speak to the students about honeybees. Von Frisch replied that he’d be happy to return, but that he’d like to talk to the students about his fascinating new discoveries on fish since he already talked about bees during his previous visit. No thank you, the teacher replied, bees please.

And finally, the precise and compelling experiments with which von Frisch deciphered the bees’ dances, belie the very messy circumstances in which they were made. Von Frisch puzzled out the second (and enduring) version of the honeybee dance language during WWII, in the Germany Reich, and with funding from the Nazi Ministry of Food and Agriculture. This after von Frisch had been declared one-quarter Jewish by the Nazi government and was threatened with an imminent ouster from his position at the University of Munich. And yet, von Frisch was able to argue for the importance of the bees to the war effort and was able to conduct some of his most important work during this period. If you’d like to learn more about the personal and professional fate of von Frisch during the war, you can read a more detailed account in my recent book on von Frisch, The Dancing Bees: Karl von Frisch and the Discovery of the Honeybee Language (Chicago, 2016).

And if you’d like to see the bees’ dances in action, there are many videos online. Here’s one that does a nice job showing the waggles during the figure-eight dance. You can also appreciate how difficult it must have been to track and decipher the bees’ dances in the tangle of the hive. In this video, the scientists have helpfully marked the dancing bee with a blue dot. And as you watch it, feel free to cue some dance music to usher in your week.

Tania Munz is the Vice President for Research & Scholarship at the Linda Hall Library. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to munzt@lindahall.org.