Scientist of the Day - Jules Dumont d’Urville

Jules Dumont d'Urville, a French naval officer and scientist, was born May 23, 1790. He served on three of the greatest French scientific voyages of the 19th century, once as second in command (to Louis Duperrey) on the voyage of the Coquille (1822-25), which collected specimens in Melanesia and Papua New Guinea, and twice as the commander of the Astrolabe, whose first voyage (1826-29) was a search for the comte de Lapérouse, whose ships had gone missing in 1788 near the Solomon Islands, and the second an exploration of the southern oceans and a search for the South Magnetic Pole (1837-40). Actually, since the Coquille was renamed the Astrolabe after her first voyage, Dumont d'Urville sailed the same ship around the world three times, twice as commander.

In the annals of scientific voyages, that is, of voyages intended to explore, collect specimens, and map new seaways, each was immensely successful. Tens of thousands of specimens were brought back to the Museum of Natural History in Paris, many of them invertebrates, which had not been high on the priority list in the days of Captain Cook. For the second and third voyages, Dumont d'Urville was in charge of writing up the expedition narratives, which, in the case of the search for La Perouse, amounted to some 13 text volumes and 8 beautiful folio atlases.

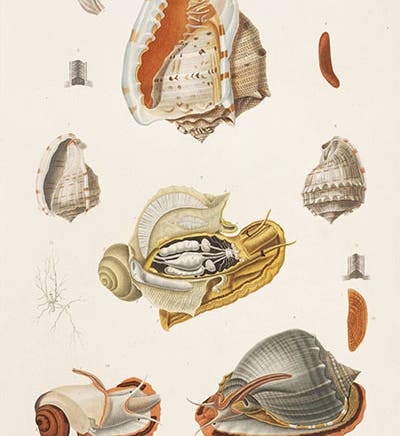

When we mounted our 2009 exhibition, The Grandeur of Life, we wanted the most glorious images possible to honor the exhibition theme, and one of the atlases from the first Astrolabe voyage was selected for display, because of the beauty of the invertebrate plates. Here we show one of those, depicting three species of helmet snails (first image). We displayed our two favorite plates in the exhibition, showing a sea hare, and a sea anemone (be sure to click on the images at the link to enlarge them). We should point out that Dumont d’Urville had nothing to do with collecting these specimens or drawing them – he had excellent naturalists and artists on board for that purpose. But he was in charge of the voyage, and he did edit the volumes and commission the engravings, so he does deserve some of the credit.

The third voyage, of the Astrolabe and a companion ship, Zélée, to Antarctica, was less sensational, although certainly quite eventful, as sailing among ice floes is apt to be. They couldn’t reach the South Magnetic Pole, which was inland, and they could only see, but not land on, the continent of Antarctica. But they claimed a large area for France, named Adélie Land, after Dumont d’Urville’s wife Adèle, who also supplied her name for the Adélie penguin. And the narrative and plate volumes that Dumont d’Urville edited and published on his return are beautifully done, with black and white engravings (as befits the Antarctic) that are breath-taking. We displayed two plates from this work in our 2008 exhibition, Ice: A Victorian Romance .

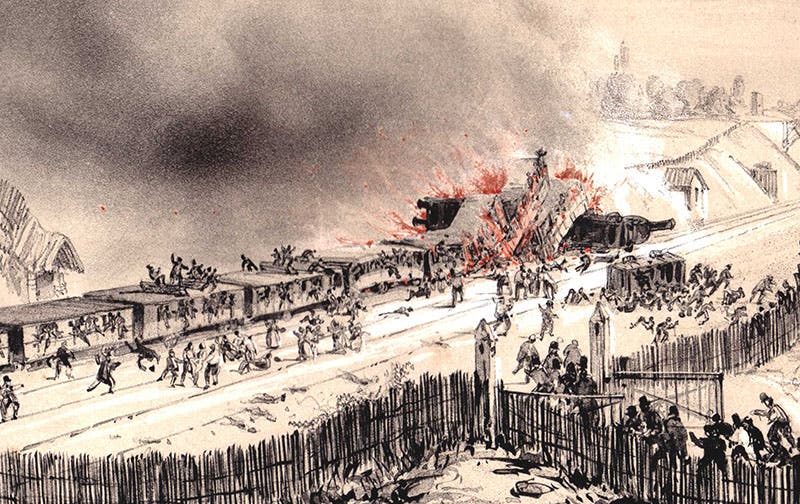

You may have noticed that Dumont d’Urville was born on May 23, and not on today's date. We chose to commemorate him today instead of on his birthday later this month, because May 8 was the day of his death, and a dramatic passing it was. On this day in 1842, Jules, his wife Adèle, and their children boarded a train in Versailles for Paris. As the train passed Meudon, an axle on the locomotive snapped, the engine derailed, the firebox ruptured, and the tender and locomotive erupted in flames. The passenger cars behind overran the engine and caught fire as well (second image). Since the practice in those days was to lock passengers in their compartments, few in the first few cars escaped the flames. Dumont and his entire family perished. The Versailles rail accident, as it is now called, was the first real train disaster in history, killing somewhere between 50 and 200 people; it was a sad way for a distinguished naval family to meet their end.

There is an oil portrait of Dumont d’Urville, painted in 1846 by Jér�ôme Cartellier, at Versailles. If the date is correct, then this was a posthumous portrait.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![Columbine, hand-colored woodcut, [Gart der Gesundheit], printed by Peter Schoeffer, Mainz, chap. 162, 1485 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/3829b99e-a030-4a36-8bdd-27295454c30c/gart1.jpg?w=210&h=210&auto=format&fit=crop)