Scientist of the Day - Jules-César Savigny

Jules-César Savigny, a French naturalist, died Oct. 5, 1851, at age 74. Savigny was invited to join Napoleon's scientific expedition to Egypt in 1798, taking the place of Georges Cuvier, who was unable (or unwilling) to go. Although only 21 years old when the expedition began, and trained as a botanist rather than a zoologist, Savigny nevertheless became an accomplished student of birds, and took a special interest in the ibis, whose mummified remains were found by the thousands in Egyptian tombs.

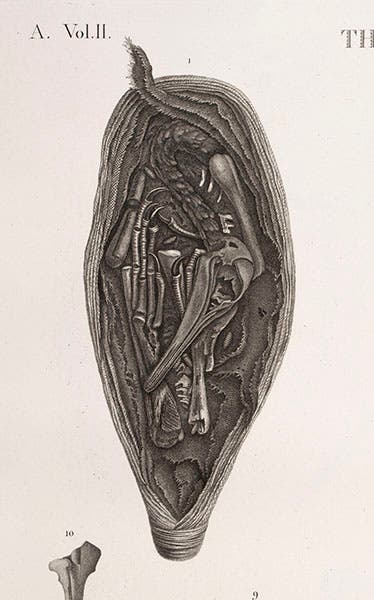

Herodotus, the Greek historian, related a story told to him about the supposed annual invasion of Egypt by flying snakes, which was controlled by flocks of ibis flying out to meet and devour them. The French found that, typically, the mummified remains of ibis specimens did have snakes in their stomach cavities. However, Jules-César Savigny, who investigated the habits of the ibis, discovered that the ibis eats shellfish, not snakes, and he noted that the embalmers had apparently been serving “truths deeper than mere facts of natural history.”

Upon his return to France in 1801, Savigny wrote a Natural and Mythological History of the Ibis, which was the first zoological treatise from the expedition to be published (in 1805). Cuvier, who had sent Savigny to Egypt in his stead, took a great interest in the ibis mummies, for the ancient remains were identical to the skeletons of the modern ibis. This seemed to be evidence for the fixity of species, and against the evolutionary ideas of his compatriot, Jean-Baptiste Lamarck. Cuvier included discussions of the ibis and its fixed skeletal type in the introduction to his Recherches sur les Ossemens Fossiles (1812), which was subsequently published separately in many editions as the Discourse sur les Revolutions de la Surface du Globe.

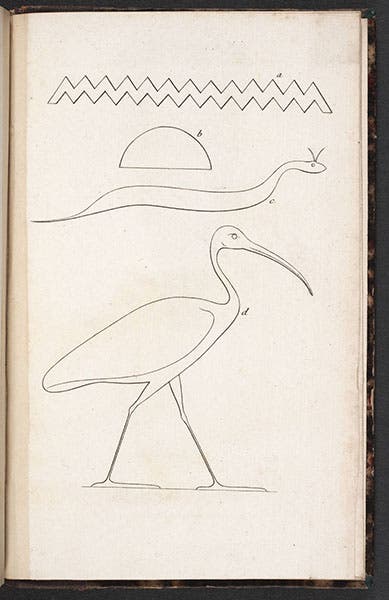

Ibis hieroglyphic, Savigny, Histoire Ibis, 1805 (Linda Hall Library)

Savigny later contributed to the sections on birds and invertebrates that appeared in the zoology volumes of the great Description de l'Egypte (1809-28), ensuring that the engraved plates were as accurate as possible. Sadly, as he was ready to prepare the text for the engravings, about 1820, he began to suffer from a very painful nerve disorder affecting his eyes, so that he could not bear sunlight and had to wear a black veil most of the time. He was not able to work on the text, or even discuss it, and it had to be completed by another young naturalist who was not allowed to tell Savigny what he was doing, or even to speak with him. It was not a happy situation, to say the least. Savigny lived for another thirty years with this affliction. We displayed his book on the ibis, and several of the zoological volumes of the Description with his illustrations, in our 2006 exhibition, Napoleon and the Scientific Expedition to Egypt.

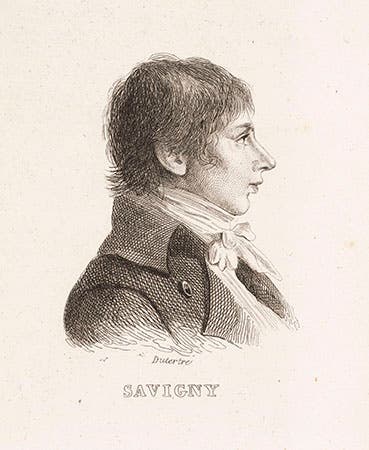

Portrait of Savigny, in Reybaud, Histoire, 1830 (Linda Hall Library)

The images of the black and white ibis and the ibis mummies are from the Natural History plate volumes of the Description. The ibis hieroglyph is from Savigny's 1805 book on the ibis. The portrait was taken from Louis Reybaud's Histoire de l'expedition francaise en Egypte (1830-36), where one can find sketches of most of the savants that accompanied Napoleon on the Egyptian expedition, including one of Napoleon himself.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.