Scientist of the Day - Joseph Whitworth

Joseph Whitworth, an English engineer and manufacturer, was born Dec. 21, 1803. Whitworth was an important figure, perhaps the most important figure, in bringing precision engineering to the Victorian industrial revolution. He apprenticed in the London workshop of Henry Maudslay, who was the most important advocate for precision machining before Whitworth. In addition to inventing the screw-cutting lathe, which made it possible to have interchangeable screws, Maudslay had maintained that the first step in developing precision machinery was being able to machine a perfectly flat surface plate. Once you had a standard of flatness, you could make other things that were straight and true. Maudslay was able to machine surfaces that were accurate to a thousandth of an inch. But Whitworth, who set up his company in Manchester in the 1830s, was able to make surfaces that were a hundred times flatter. In consequence, everything else he made was a hundred times truer. There are some actual Whitworth surface plates in the Science Museum London, but I could not find any good images of them, and they don't look like much anyway. But the SML has a dozen Whitworth machine tools that look beautiful – planers, slot-cutters, and an impressive gear-cutting machine that you can see below.

Whitworth is perhaps best known for establishing standards for screw-cutting, standards that were accepted across England and are still known as British Standard Whitworth, or BSW. Maudslay had made it possible to make identical screws, but there are lots of variables in screw production – the pitch, the angle and depth of the threads, the radius of the small curve at the bottom of each thread. Whitworth suggested that the standard thread angle should be 55 degrees, and set similar standards for the other variables. After BSW was accepted, then screws at last became truly interchangeable.

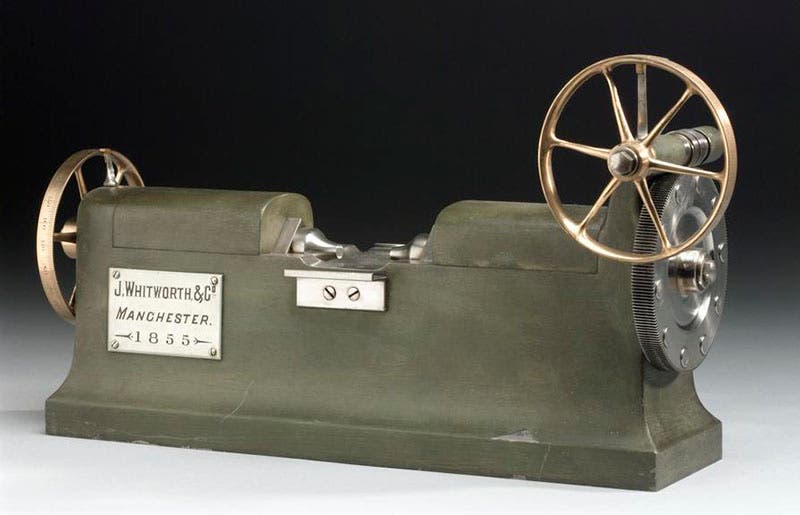

Whitworth's most amazing invention was his measuring machine. Insuring that two objects are precisely the same length is very hard to do by optical measurement. So Whitworth invented and built a small measuring engine that looked rather like a miniature lathe. At the end of each spindle is a small absolutely flat surface, and the spindles are advanced by screws that are turned by large wheels with finely calibrated scales. Place a small object between the plates and tighten the screws until the object is held lightly in place. Then withdraw the screws slowly until the object is released. You can read its exact length from the scales. Better yet, you can take a second object that is supposed to be the same length and see it if is indeed the same length. Whitworth's measuring engine was accurate to within one-millionth of an inch, an unheard-of accuracy in mid-Victorian Britain. The Science Museum in London has two of these machines, both stamped “Whitworth 1855.” The handsomer one, with the parallel plates more visible, is the one above (third image). But the measuring engine below, with the plates concealed, is the more impressive one, because it has a worm drive on the main wheel that gives it the .000001 accuracy.

Whitworth also made an improved rifle, when the Crimean War made the need for a better rifle apparent. It had a hexagonal, tightly rifled barrel that fired a hexagonal bullet, and it was phenomenally accurate over long distances. In a famous demonstration in 1860, Queen Victoria fired a Whitworth rifle at a target 400 yards away and hit the bullseye, less than an inch off center. Granted, the rifle was fixed in position, and she fired it by pulling a thread, but still, there were very few rifles anywhere that could hit an inch-wide target that far away, no matter how well fixed and aimed the rifle was. Interestingly, the War Office never bought Whitworth rifles for their soldiers, citing cost factors. Instead, many of the Whitworth rifles went to French troops, and the Confederate Army, where it proved to be the perfect sniper's rifle, as several Union generals learned the hard way.

Whitworth became a wealthy man because of his machine tools and rifles, and to his credit, he gave most of it back, mostly to the city of Manchester, where he endowed a hospital and a college, and founded the Whitworth Art Gallery. His portrait hangs in the gallery, his left hand resting on his measuring engine (first image). The Whitworth recently installed an exhibit honoring their benefactor: "Standardisation and Deviation: The Whitworth Story”, which I believe closed earlier this year.

Whitworth spent his last years at an estate in Darley Dale, Derby; he died in 1887, at age 83, and is buried there. Whitworth Park, in Darley Dale, honors him with a memorial plaque (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.