Scientist of the Day - Jorge Juan y Santacilia

Jorge Juan y Santacilia, a Spanish military officer, was born Jan. 5, 1713. In 1735, fresh out of officer's school and only 22 years old, Juan was asked by King Philip V to travel to Ecuador (then called the Viceroyalty of Peru) to take part in a French scientific expedition that intended to measure the length of a degree of latitude at the equator. His travelling companion was an even younger and equally raw fellow officer, Antonio de Ulloa. They left Cadiz in May of 1735, met up with the French delegation in November, and then set out for Quito.

The French intended to measure the length of a degree in a country near the equator (Ecuador), and again in a northern country (Lapland); it was hoped that by comparing these measurements, one could determine whether the Earth is a sphere, an oblate spheroid (like an onion), or a prolate spheroid (like a lemon). The Ecuador contingent consisted of Charles-Marie de La Condamine, Pierre Bouguer, and Louis Godin; the Lapland enterprise enlisted the services of Pierre-Louis Moreau de Maupertuis, Alexis-Claude de Clairaut, Abbé Outhier, and Anders Celsius; we have written posts about four of these scientists, although only in the case of Bouguer and Outhier did we discuss the geodetic expeditions.

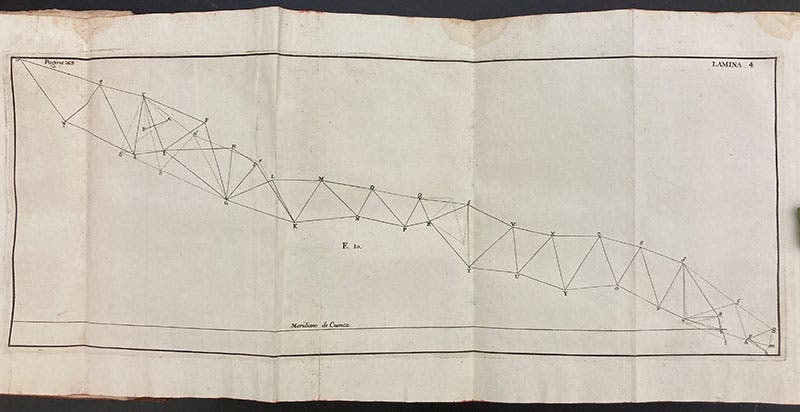

The reason why Juan and Ulloa were sent along with the French equatorial expedition is that the French would be working in Spanish territory, and having smart Frenchmen wandering about unchaperoned in Spanish lands did not seem like a good idea to the Spanish crown. As it turns out, Jorge Juan was also a good mathematician, and he kept a complete record of all the observations and calculations made by the French, adding quite a number of his own. Measuring a degree along the Earth's surface is done by careful triangulation. One first lays out a base line, using measuring rods that are exceptionally accurate. The base line near Quito was 7 miles long. Then, from the endpoints, one carefully determines the position of a third point, a cairn or tower, to form a triangle. From the new third point, and the first, a fourth point is triangulated, and then a fifth, and a sixth, and so it proceeds, a chain of triangles, up and down hills, and across the countryside. The latitude of the original base point is determined astronomically, with what is called a zenith transit instrument. The latitude of the end point is determined the same way, and the difference between the two is the distance triangulated in degrees, typically one degree and a fraction. When this is compared to the triangulated distance in miles, the length of a degree can be determined.

The enterprise lasted a long time – nine years – much longer than should have been necessary (the Lapland survey finished their work in a single season). One of the factors that delayed matters is that La Condamine wanted to erect pyramids at each end of the baseline, with plaques praising the French effort, and a French fleur-de-lis crowning each monument. Juan y Santacilia did not want such overtly French monuments erected in the Viceroyalty of Peru, objected to the deprecating words that described the Spanish contribution to the survey, and took the matter to court. Eventually, the Spanish prevailed; the pyramids were built, but without the French symbols on top, and the inscriptions were ordered to be corrected. With matters apparently resolved, Juan and Ulloa sailed home, travelling separately (each with duplicate copies of all observations), with Juan arriving safely in October of 1745. Ulloa was captured by the English, but was eventually released and returned to Spain in 1746.

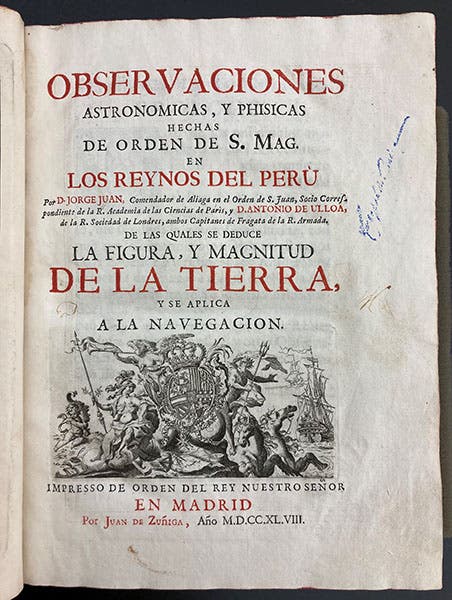

The scientific outcome of the Spanish expedition was a joint publication by Juan and Ulloa, Observaciones astronomicas, y phisicas: hechas de orden de S. Mag. en los reynos del Peru (1748), one of the five published accounts of the Ecuadorian survey (the other four being French). We have all five works in our History of Science Collection.

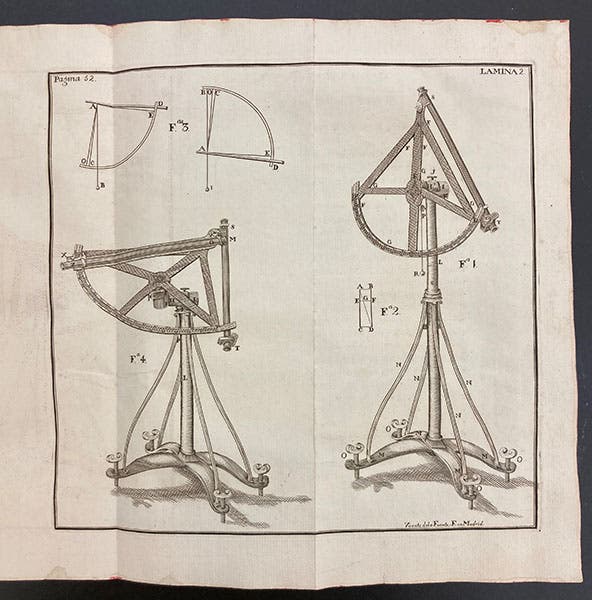

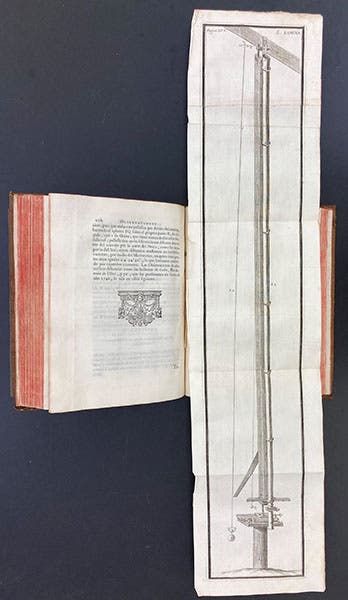

Juan and Ulloa's book opens with a frontispiece that visually presents the conclusion of all this triangulation – the globe of the Earth is clearly oblate, flattened at the poles (first image). The book also contains several engravings of instruments, one showing the theodolite quadrants used for triangulation (third image), and one depicting the transit instrument. There is also a map of the chain of triangulations (fifth image). The most striking plate depicts the 20-foot zenith sector; the plate has four folds, and since the telescope is used in a vertical position, the plate folds up and down, not left and right (sixth image). There are no plates in this work that show the actual process of triangulation; for that we refer you to the book by Jean Picard, who was the first to measure a degree of latitude, that of Paris, 70 years earlier.

There is a portrait of Jorge Juan y Santacilia in the Naval Museum in Madrid (second image); the medal indicates that he was also a Knight of Malta.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.