Scientist of the Day - John Graunt

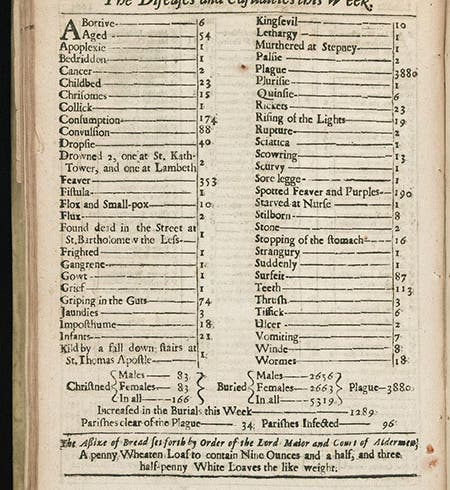

John Graunt, an English tradesman, statistician, and epidemiologist, was born Apr. 24, 1620. To call Graunt a statistician and an epidemiologist, while true, is misleading, because neither discipline existed until Graunt published his milestone book, Natural and Political Observations Made Upon the Bills of Mortality, in 1662. As the title indicates, Graunt focused his attention on what were called "Bills of Mortality," death records for greater London that been initiated in 1604, in an attempt to keep track of the devastation wrought by the plague. The task of compiling the records was assigned to the Company of Parish Clerks, and the census takers, called Searchers, were elderly women who would visit every death victim and try to ascertain the cause of death. Every week the results from each parish were compiled and collected, and on Thursday, a Bill of Mortality was drawn up, listing the numbers of deaths attributed to each cause for that week. After 1625, these were printed and could be had by subscription. The most famous bill of mortality, often reproduced, is one compiled after Graunt wrote his book, issued for the week of Aug. 15-22, 1665, when the bubonic plaque was wreaking havoc on London (first image). It is sobering to see that 54 people died of old age and 23 in childbirth, but 3880 succumbed to plague in that one week. At the end of the year, the weekly bills were compiled into an annual one. We see here a bill for 1632, which Graunt reproduced in his book. That was not a plague year, only one person dying of it, but consumption, infant deaths, and fever took their toll. It is hard not to smile at entries counting people who died "Affrighted" or "Suddenly" or of “Griefe,” and I confess to having being amused when I saw my first bill of mortality, but there is really nothing funny about the many forms of death. Did you notice that only 7 people were murdered in all of London that year? In some ways, 17th-century cities could be more civilized than those of modern times. The bills of mortality were compiled for 60 years, available to all, before anyone made any use of them. Graunt appears to have been the first to ask: what can we learn from these documents? Equally important, he asked: how reliable is the data? For example, during plaque years, if a member of a household were known to be a plague victim, the entire family would be quarantined. Consequently, it was certainly possible that those who could afford to might bribe the searcher to assign a different cause of death. So Graunt looked at the death statistics for normal years flanking the plague years, came up with an estimate for how many deaths were to be expected each year, and then surmised that the deaths in excess of that number were probably due to plague. For example, if the average ordinary deaths in 1624 and 1626 were about 8000, and if in 1625 there were 17,000 ordinary deaths listed, then probably 9000 of those were actually extraordinary, i.e., due to the plague. So not only was Graunt doing statistical analysis for the first time, he was critically evaluating the data. Grant compiled his own tables from the published bills and managed to find a way to estimate life spans and ages at death, no easy task, since the bills of mortality did nor record the ages of death victims. It was, all in all, an extraordinary and unprecedented accomplishment, especially for a man who earned his living as a tradesman.

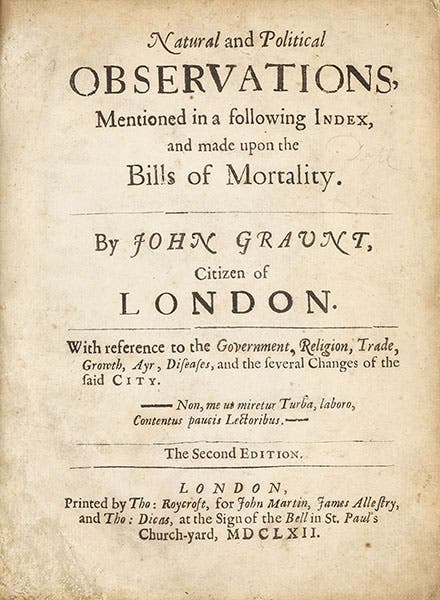

Graunt dedicated the first edition of his book to Robert Moray, the president of the Royal Society of London, which received its charter the very year his book was published, and Graunt was soon made a Fellow of the Society. All later editions – there were five in all – announced his status as Fellow prominently on the title page. The first two editions of 1662 gave him only the title, Citizen of London (second image). We do not have any edition of Graunt's book in our collections, or even any books about Graunt, which is a pity, given the importance of data analysis for most scientific enterprises these days. Accordingly, we are very happy to honor him here. The title page we show, from the second edition of 1662, was taken from the website of a book dealer who is offering it for sale, if you are interested. There is a supposed portrait of Graunt that you will find on Wikipedia and other sites, but it has no pedigree that I can discover, having first appeared in a 1936 book on insurance. The fact is, we have no idea what Graunt, and thousands of other prominent London artisans and merchants, looked like. Only the well-to-do could afford to sit for a portrait artist. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.