Scientist of the Day - Johann Gregor Mendel

Johann Gregor Mendel, a Moravian monk, was born July 20, 1822. When he was 21, he joined the Augustinian friars at the Abbey of St Thomas in Brno, motivated less by religious conviction than by the hope that entering a brotherhood would ease both his financial and educational concerns. While most of the friars at Brno were teachers at the local gymnasia, Mendel in 1856 turned to the study of plant hybridization. Eight years later, he had completed his now-famous statistical study of Pisum (pea-plant) hybrids. In order to explain the rather curious results, especially the reappearance of certain traits in the second generation in a 3:1 ratio, Mendel proposed the existence of paired hereditary particles (later to be called genes) that were contributed to the offspring by each parent. He was able with his postulates to explain the 3:1 ratio of traits. Mendel announced his results, and his explanatory postulates, in two papers that he read to the Natural History Society of Brno in 1865. In 1866, the papers were published in the Verhandlungen (Proceedings) of the Society. We have those volumes in the vault of our History of Science Collections.

Modern genetics was born with Mendel's 1866 papers, but it was a strange kind of birth, since the child lay in a state of suspended animation for 34 years. The Brno Society was not the Royal Society of London, but it was a respectable group, and its Verhandlungen were fairly widely distributed. We know, for example, that a copy of the Mendel issue made it into the Library of the Linnean Society of London, where Darwin's first short paper on evolution by natural selection had been read in 1858. But Darwin never saw Mendel's papers, and it is not clear that even if he had, Darwin would have read them or grasped their import, since they were about hybrids, not new varieties or species. Other plant experimenters who read the papers misunderstood or ignored them. Mendel was rather baffled by the silence that greeted his work, and he did some more work in the field, but in 1868, he became Abbot of the monastery, and he gave up his hybrid experiments to guide the Abbey through the difficult decade of the 1870s. When he died in 1884, Mendel was unaware that he had laid the basic foundation of modern genetics, and so was everyone else in Europe. Not until 1900 were Mendel's papers rediscovered and his work duplicated, by three researchers independently, and the Mendelian revolution, on hold for far too long, could begin in earnest.

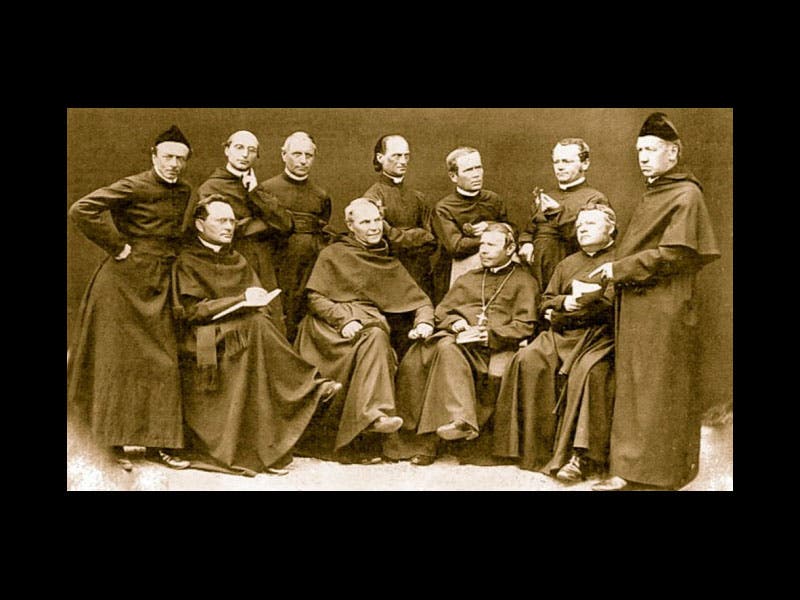

Mendel is well appreciated in his native land. The statue (first image) is outside one of the entrances to the still-thriving abbey of St Thomas in Brno (second image). There are several photographs of Mendel, but the most charming is a group photo of all the monks (third image), Mendel (second from the right in the back row) clutching a plant, while everyone else holds textbooks. The postage stamp (fourth image) was issued by Austria in 1984, during the centennial of Mendel’s death.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.