Scientist of the Day - Jocelyn Bell Burnell

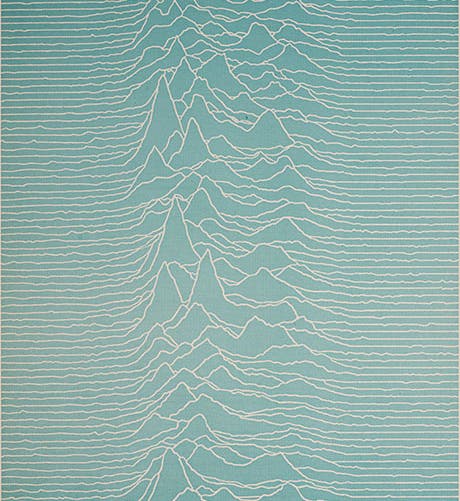

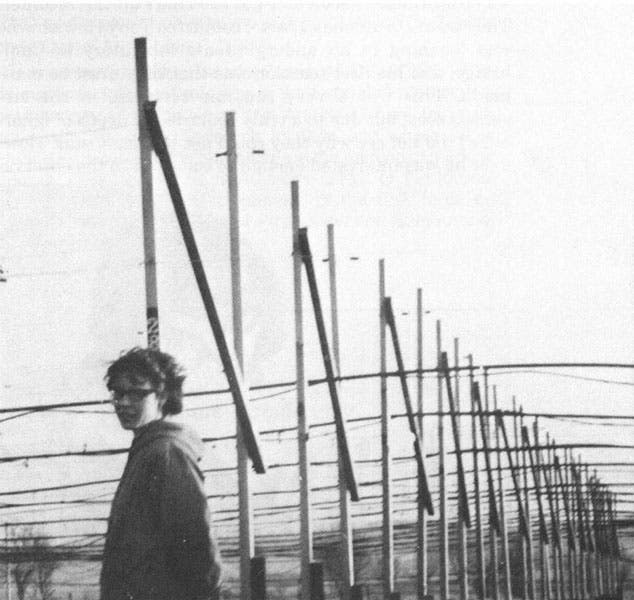

Jocelyn Bell, an Irish astrophysicist, was born July 15, 1943. Bell was a graduate student at the University of Cambridge in 1967 when she and 4 other students built a crude radio telescope to pursue their PhD thesis research. They set over 1000 posts on a 4 ½ acre field and strung miles of wire. Radio astronomy was then a hot subject, ever since quasars had been identified in 1963 as star-like objects that emit intense amounts of radio waves. Perhaps, it was thought, there were other radio sources out there, waiting to be discovered. With her radio ears and eyes, Bell scanned the skies and recorded the noise received as squiggles on a paper tape recorder. On Nov. 28, 1967, she noticed that the recorder had picked up something odd from the direction of the constellation Vulpecula – a pulse, an intermittent signal with a precise period of 1.33 seconds. We see here a later chart, showing 80 pulses of the mysterious object, then known as CP 1919, stacked up to highlight the 1.33 second regularity (first image).

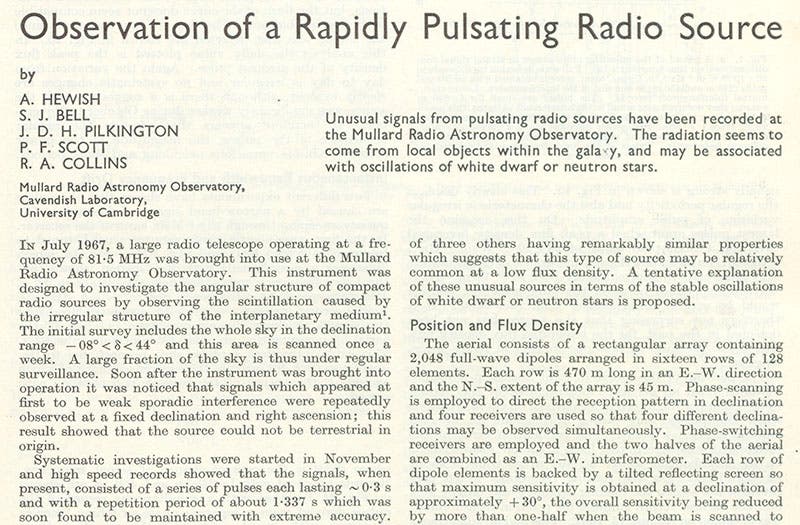

This was all quite exciting, since pulsed radio waves from outer space were being eagerly sought by SETI people (searchers for extra-terrestrial intelligence), and the object was temporarily labelled LGM 1 (for Little Green Men 1), as if ET were trying to phone home (although this was well before the movie ET tried to do just that). However, other such pulsars were discovered in other parts of the sky, which ruled out some sort of exterrestrial communication. With her thesis advisor, Antony Hewish, and three others, Bell published a landmark paper in Nature in 1968, titled: "Observation of a rapidly pulsating radio source” (third image). Initially the identity of these pulsars was perplexing, since things the size of stars do not ordinarily oscillate with periods as short as one second. But theoretical astrophysicists soon came to the rescue, pointing out that this is exactly how a very dense hypothetical object known as a neutron star might behave, rotating very swiftly and slinging out radiation like a searchlight beam. Bell’s pulsar and the others subsequently discovered were seen as confirmation of the hypothesis that exploding red giant stars would produce rapidly rotating neutron-star remnants at their core.

In 1974, Anthony Hewish was awarded a half-share of the Nobel Prize in Physics “for his decisive role in the discovery of pulsars.” The other half-share did not go to Jocelyn Bell, but rather to Martin Ryle for a completely different achievement. Bell did not share in the prize, and in fact she was not even mentioned in the citation. This raised quite a stink at the time, and the odor has not entirely dissipated 45 years down the road. Many people protested, the most vocal being English astrophysicist Fred Hoyle, who raked the Nobel committee over the coals for denying Bell a share of the Prize. Many feel that his caustic vehemence cost Hoyle a chance at his own Nobel Prize, which he certainly deserved for his discovery of nucleosynthesis in stars. Bell herself took it very well. She said later that she should not have shared in the prize – that Nobel Prizes should not be given to graduate students, as this would demean the award. Many would agree with that. But why then award a prize for the discovery of pulsars at all? Hewish really contributed little to the discovery except for supervising Bell’s work, and he actually had to be convinced by Bell that the sources of the pulses were sidereal in nature. It was all a very strange, and a very 1970s, development, at which today we can only shake our heads.

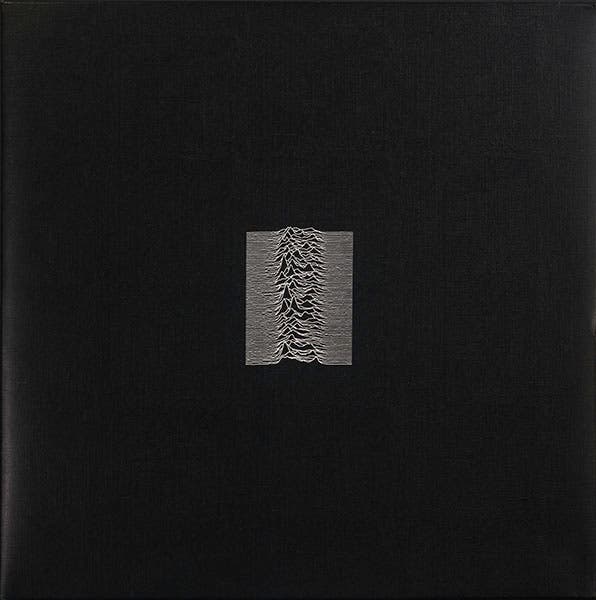

Bell has had quite a distinguished career after her Nobel snub; she has received many other honors and been elected president of a variety of scientific societies, and in 2007, she was made a DBE, or Dame Commander of the British Empire (fourth image), which, coupled with her acquisition of a husband earlier, means she is now known to the world as Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell. One of the odd spin-offs of Bell’s discovery of pulsars is the elevation of the 80-period pulsar graphic into a cultural icon. The graphic was created in 1970 by Harold D. Craft, Jr., of Arecibo Radio Observatory for his PhD dissertation; the original had black pulses stacked up on a white background. It was then picked up and rendered in white-on-aquamarine by Scientific American in 1971 (first image), and was further featured in the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Astronomy in 1977, now back to black-on-white. From there, it came to the attention of Peter Saville, a young graphic designer who was trying to come up with a cover-art design for the debut album of a post-punk rock group called Joy Division.

Cover of the record album Unknown Pleasures, by Joy Division, redesigned by Peter Saville from the original graphic by Howard D. Craft, Jr., 1979 (collection of Jon Rollins)

The album, Unknown Pleasures, which appeared in June of 1979, had nothing but the stacked pulsar graphic on the front, white on black on black, with no text at all (fifth image). The album was good, but the graphic was better, with its landscape-like configuration that seemed to work equally well for galactic pulsars and rock music. The image is often reproduced and is readily available on wall posters, coffee mugs, and T-shirts, should you wish to have it close at hand. The original vinyl album for Unknown Pleasures is a little harder to come by.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.