Scientist of the Day - Jan Swammerdam

Jan Swammerdam, a Dutch microscopist and insect anatomist, was born Feb. 12, 1637. Swammerdam was one of the five great microscopists of the 3rd quarter of the 17th century, the others being Robert Hooke, Marcello Malpighi, Francesco Redi, and Antoni van Leeuwenhoek. The biological world would not see a comparable flowering of microscopy for another 150 years.

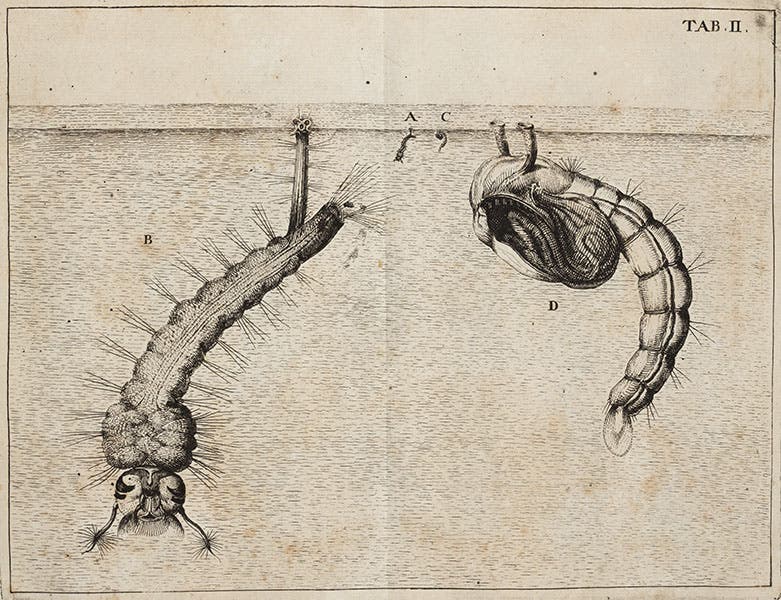

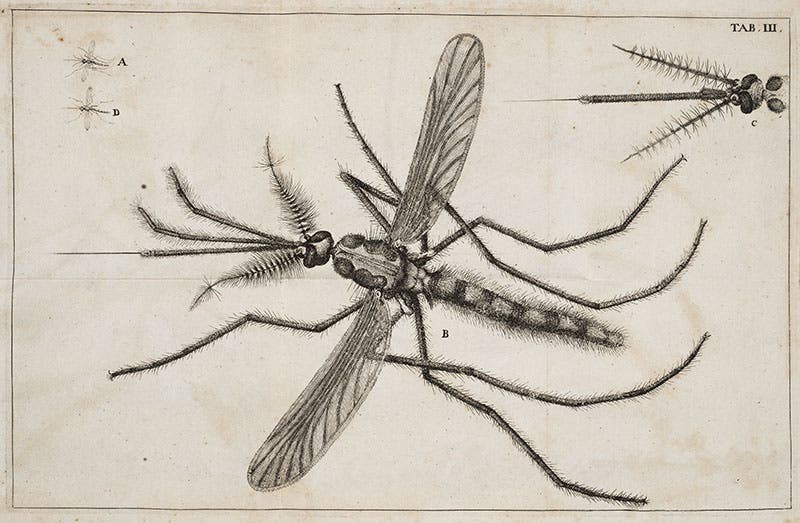

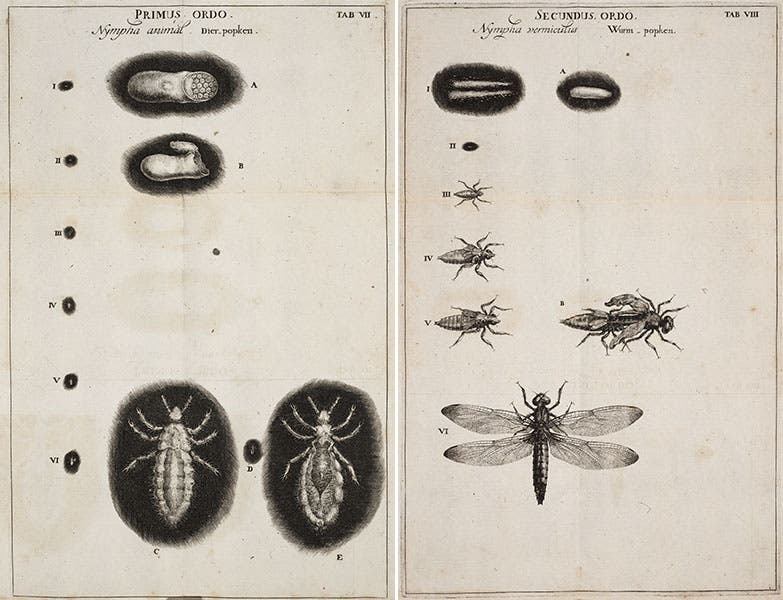

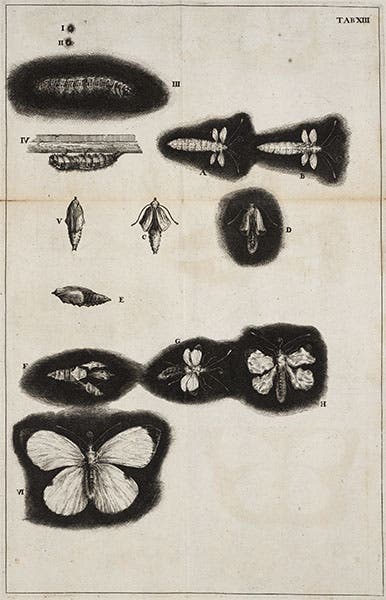

Swammerdam was particularly interested in the anatomy of insects, and in insect metamorphosis; he wanted to show that metamorphosis (the sudden appearance of new body organs) was an illusion, and that insects grew like everything else, slowly, and from pre-existing body parts. He made careful studies of insects in all their various larval, pupal, and adult stages, and claimed to have found the rudiments of wings in caterpillars, long before they became butterflies and moths. His first book, Historia insectorum generalis (A General History of Insects, 1669, which, despite its title, is in fact only a prelude to such a history), contains a variety of illustrations of insects and metamorphoses, and we have drawn on this book for our images today. We see two Daphnia (first image); mosquito larvae (second image), an adult mosquito (third image); and the various pupal and larval stages of a louse, a dragonfly, and a butterfly (fourth-sixth images). Notice, by the way, the very clever way that Swammerdam shades portions of his drawings on the metamorphosis plates so that the insects stand out dramatically on the printed page. Note also, on the mosquito plate (third image), the two natural-size insects at the upper left, contrasted with the greatly enlarged main image.To see what a good observer Swammerdam was, compare his drawing of Daphnia (first image) with the drawings in our posts on Jacob Christian Schaeffer and Louis Jurine, which were made 85 and 151 years later, respectively. There is no earlier image of a Daphnia than Swammerdam’s.

Swammerdam also did detailed studies of a mayfly, and of bees, and while the mayfly treatise was published, the notes on bees did not see the light of print in his lifetime, because poor Swammerdam, like Blaise Pascal before him, was tormented by religious doubts. In his early work, he took great joy in believing that he was revealing the glory and providence of God in his anatomical work, but by the early 1670s, he became convinced that he was pursing his studies, not for God, but for himself, which made him the worst of sinners, causing him no end of pain, and leading him to eventually give up his scientific work. Fortunately, for us, he left his manuscripts in good order, with instructions for their publication, and his Bybel der Nature, in two large volumes with atlas, appeared in 1737-8. We have this work in our collections as well, along with an English translation of the Bybel.

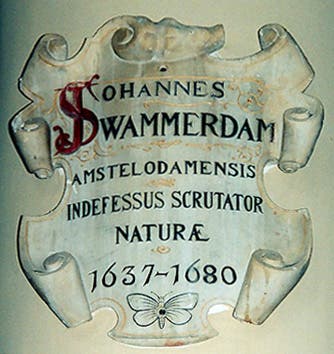

Swammerdam suffered for some years with what we think was malaria, and he succumbed to the disease on Feb. 17, 1680. He was 43 years old. There are no known portraits of Swammerdam. We know the church where he was buried in Amsterdam, but any memorial slab has been worn smooth. In 1880, on the 200th anniversary of his death, a small inscribed stone scroll was placed on a column in the church (image below). It remains his only monument.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.