Scientist of the Day - James Nasmyth

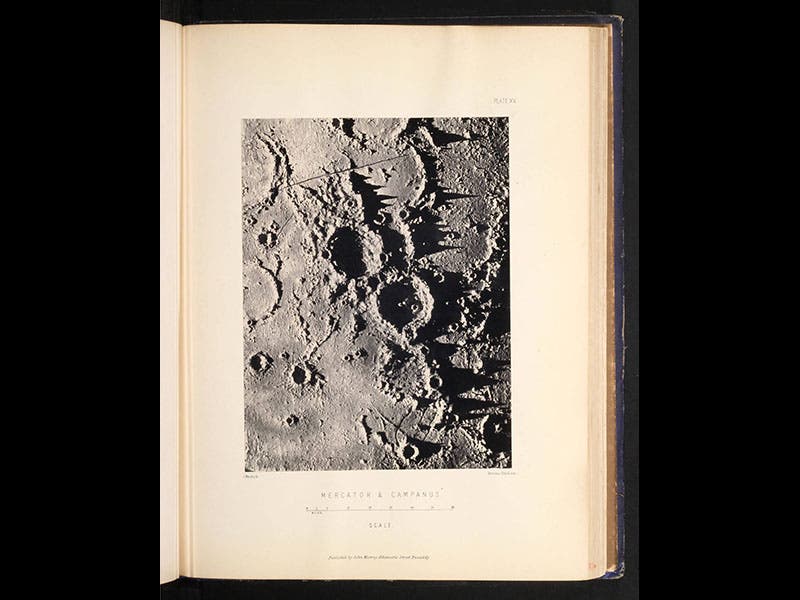

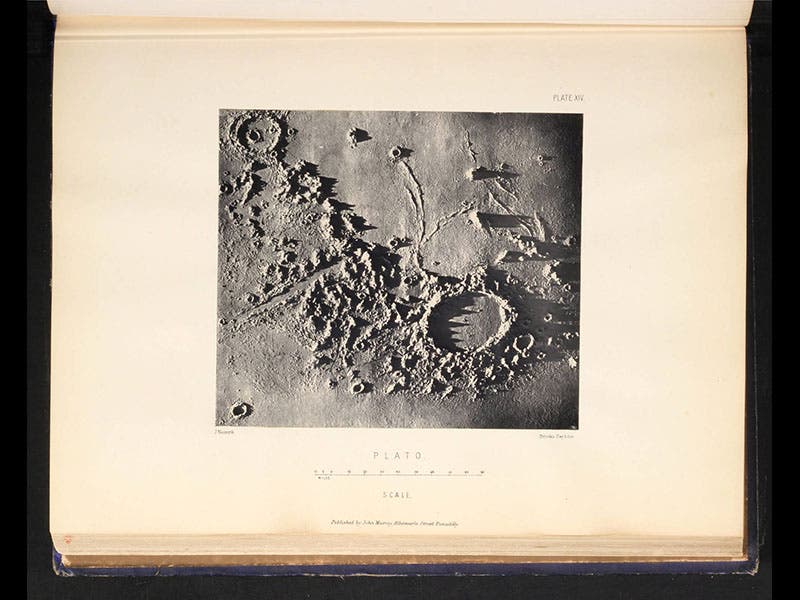

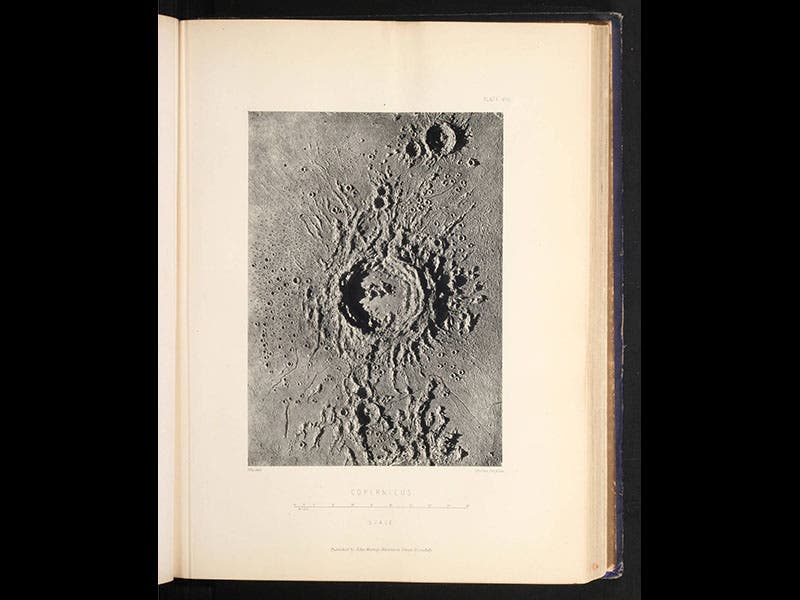

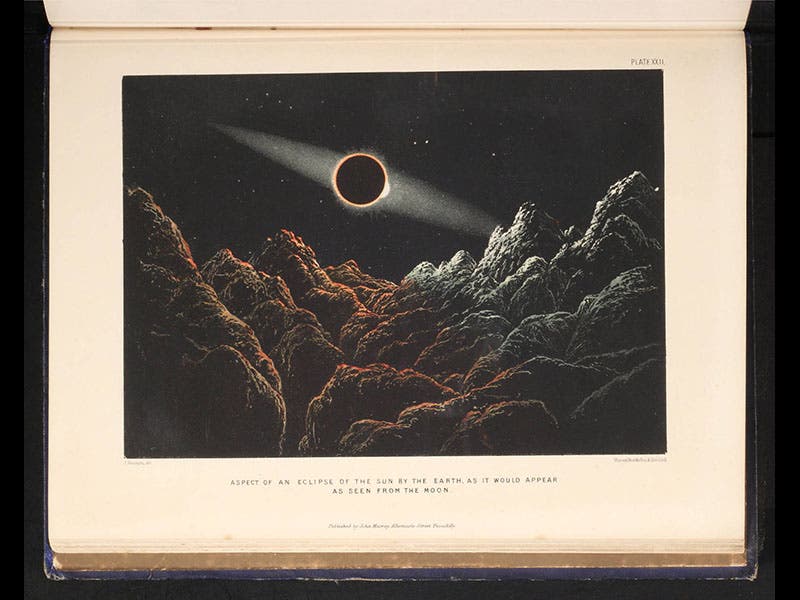

James Hall Nasmyth, a Scottish engineer and inventor, was born Aug. 19, 1808. Nasmyth is best known to historians of technology for inventing, or at least perfecting, the steam hammer, which became indispensable for forging large iron manufactures, and which made him a small fortune. But to historians of astronomy, he is remembered for a remarkable book that he co-wrote with James Carpenter: The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite (1874). The book is beautifully illustrated with heliotypes and photographic prints known as Woodburytypes. However, the surprise is that the photographs are not of the moon itself, but of plaster models that Nasmyth built after observing the moon through a telescope. We see three of the Woodburytypes above: the craters Mercator and Campanus (second image); Plato and the Alpine Valley (first and third images), and the crater Copernicus (fourth image), all made from photographs of plaster models. There is also a single chromolithograph, the last plate in the book, that shows an imagined eclipse of the sun as observed from the lunar surface, made from a photograph of a plaster set (fifth image). It looks rather like a matte painting from a 1950s science fiction movie. Even the front cover of the work is classy (sixth image), with a gold-stamped image of an erupting volcano (Nasmyth thought that lunar craters were formed by eruption, rather than impact).

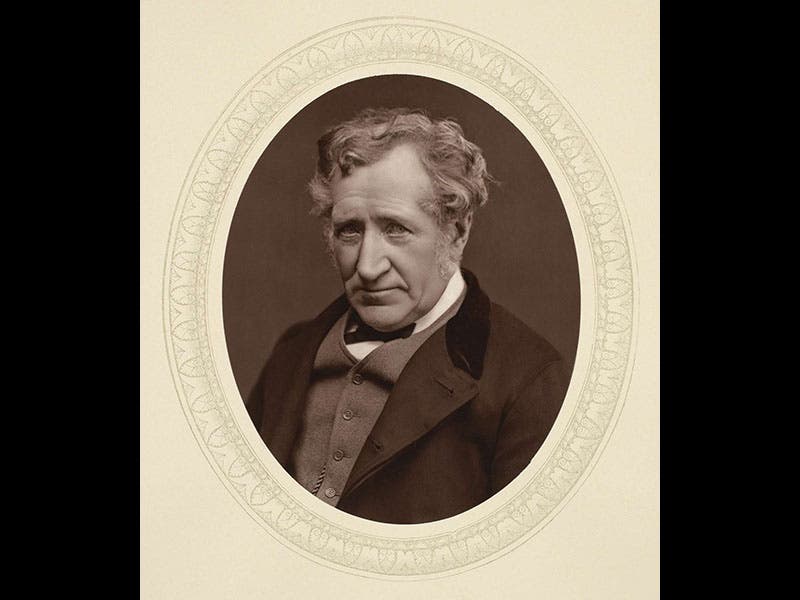

The last image above shows a photograph portrait of Nasmyth that is held by the National Gallery of Canada. It is once again a Woodburytype, and one can see why the medium was in demand for portraits, since it has a depth and richness difficult to achieve with other methods of reproducing photographs.

We displayed a second edition of The Moon in our 1989 exhibition, The Face of the Moon, where you can see yet another Woodburytype, depicting the lunar Apennines. We have since acquired three more English editions of Nasmyth’s book, including the first, and two German translations. Interestingly, the illustrations in each one are different (in the second English edition, many of the heliotypes in the first edition have been converted to Woodburytypes), which is why research libraries like to have as many editions as possible of important works like this one.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.