Scientist of the Day - James Ferguson

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

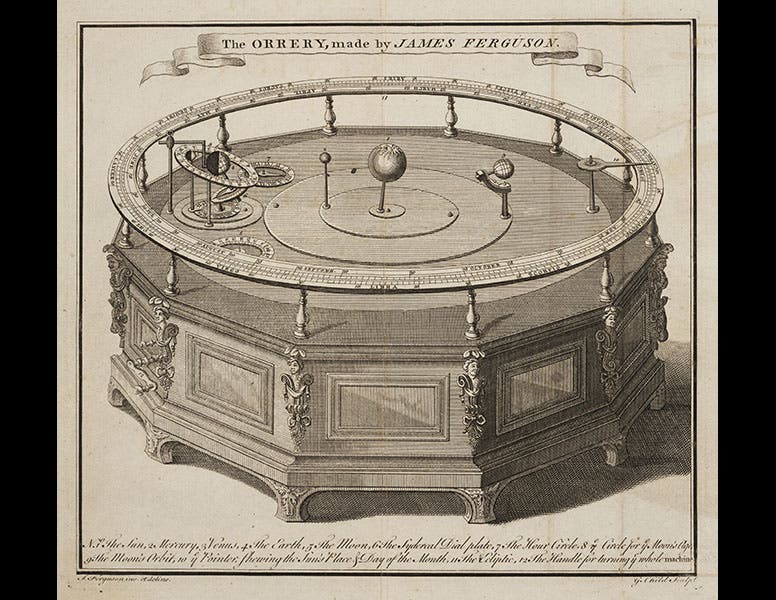

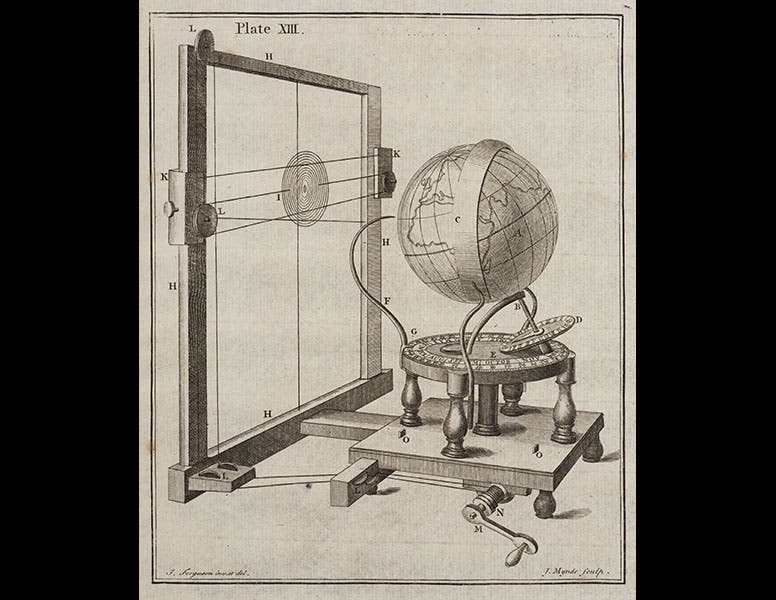

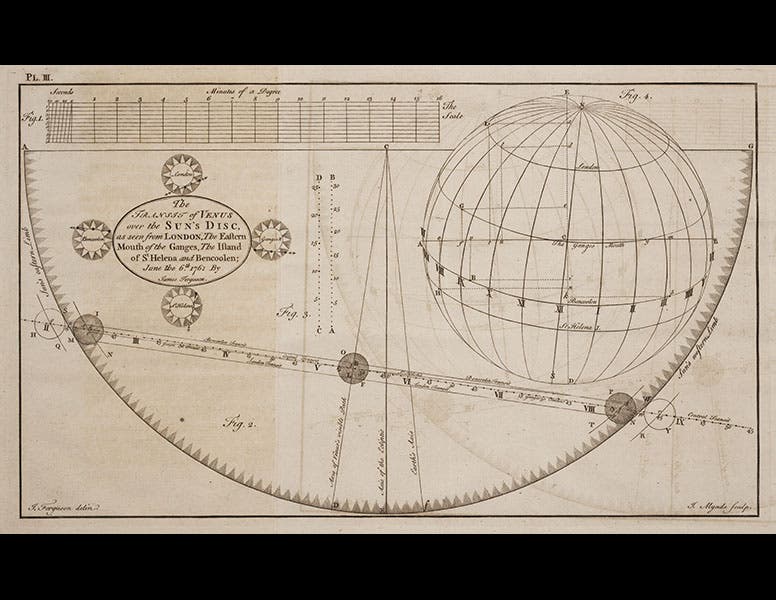

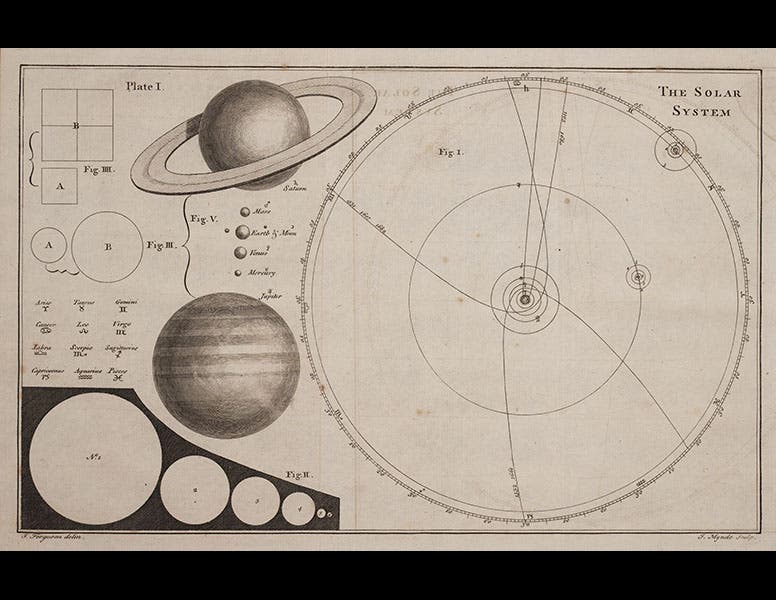

James Ferguson, a Scottish astronomical mechanic and writer, was born Apr. 25, 1710. Ferguson was a remarkable talent, who worked as a shepherd and had no formal schooling, and yet who taught himself astronomy, mechanics, and the art of limning, or portrait drawing. He came to London in 1743, making mechanical devices and publishing the odd paper in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, while earning his means by drawing portraits. His breakthrough came with the publication of Astronomy explained upon Sir Isaac Newton's Principles (1756), which was so popular it required a second edition a year later. Our Library has this second edition, and it is the source for four of the illustrations above. The frontispiece (first image) depicts an orrery that Ferguson designed and built, reportedly after he had seen another orrery, and without even looking at that orrery's mechanism. He also invented a lunar eclipse machine of which he was very proud (second image). Ferguson made a point in his book to highlight the importance of the upcoming transit of Venus of 1761 (third image), which would indeed attract the attention of the Royal Society and many other scientific societies in Europe when 1761 rolled around. And Ferguson included a plate (fourth image) that shows the solar system and the planets to scale, an engraving that calls to mind the work of Thomas Wright.

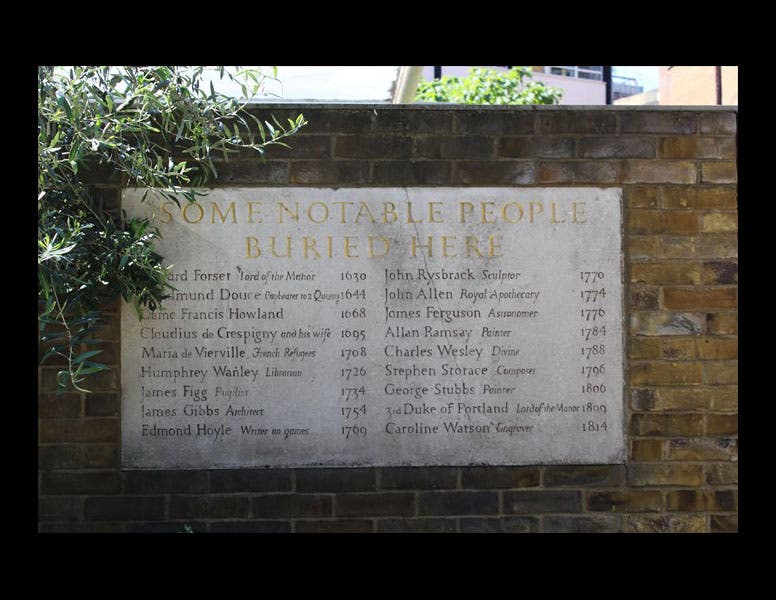

Ferguson was always complaining about his financial straits, so that the Royal Society, when admitting him as a fellow, exempted him from paying the entrance fee and dues, but when he died in 1776, he left behind an estate of many thousand pounds. He was buried in the Old Church Garden in Marlybone High Street in London, where there is a stone that records his presence there, along with the remains of the architect James Gibbs and the horse painter George Stubbs.

In 1768, Ferguson published The Young Gentleman and Lady's astronomy, a woman's guide to astronomy in the tradition of Bernard de Fontenelle’s Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds (1686). This is a charming work, which we acquired some years ago, and which we will make the subject of some future anniversary notice.

The portrait above, a mezzotint, is in the National Portrait Gallery, London (sixth image). Four of Ferguson’s portrait “limnings” are in the Science Museum, London (seventh image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.