Scientist of the Day - J.M.W. Turner

Joseph Mallord William Turner, an English landscape painter usually known as J.M.W. Turner, was born Apr. 23, 1775. Turner was remarkable in his dramatic use of light, and he greatly transformed the look of landscape painting with his proto-impressionist style. Most landscape painters of the first half of the 19th century brushed up against technology, if only because technology was changing the face of the land and the sea. We thought it might be fun to pick out several of Turner's paintings that could be used to illustrate a lecture on the Victorian technological revolution. We begin with the most obvious choice, if only because of the title: Rain, Steam, and Speed - The Great Western Railway (1844), which is in the National Gallery in London (first image). It provides us a view of a train sprinting across the Maidenhead Railway Bridge, which was built by Isambard Kingdom Brunel in 1839 as part of the Great Western Railway. It is hard to find the train and the bridge, since the painting shows mostly steam, rain, dust, and light. None-the-less, the painting is highly dramatic. Turner seems to be commenting on the new definition of speed that railroad technology is providing us. The old notion is sprinting ahead in the foreground, a hare, who seems likely to be overtaken by the iron horse. The posting of the painting on Wikimedia commons is in some ways preferable to the more complex webpage of the National Gallery, since it is easier to magnify the painting and see all the details that are hard to make out otherwise – the hare, the engine smokestack, the open carriage with its smoke-besotted occupants, the old fashioned carriage bridge off to the left. You can also see these details on the Khan Academy video, while listening to some insightful commentary.

Another painting inspired by technology.is The Fighting Temeraire (1839), also in the National Gallery. One of the spinoffs of the industrial revolution was obsolescence, something quite foreign to life before 1800. This once-mighty warship, which had helped win the Battle of Trafalgar for Lord Nelson, was being conveyed by the ugliest of steam tugs to a shipyard to be broken up for scrap, its life of service over. The sad fact that beautiful sailing ships were being replaced by grown-up versions of the smoky tug seems to have been in Turner's thoughts – it certainly comes to the mind of the modern viewer. The painting played a small role in the James Bond film, Skyfall (2012), in the scene early on where Bond first meets the new Q in the National Gallery and they sit before Turner’s Fighting Temeraire, as young Q comments: “Always makes me feel a little melancholy. Grand old war ship, being ignominiously hauled away for scrap... The inevitability of time, don't you think?" Old Bond, threatened with obsolescence himself, is not amused. You can see a two-minute clip here, although the first 40 seconds will certainly suffice.

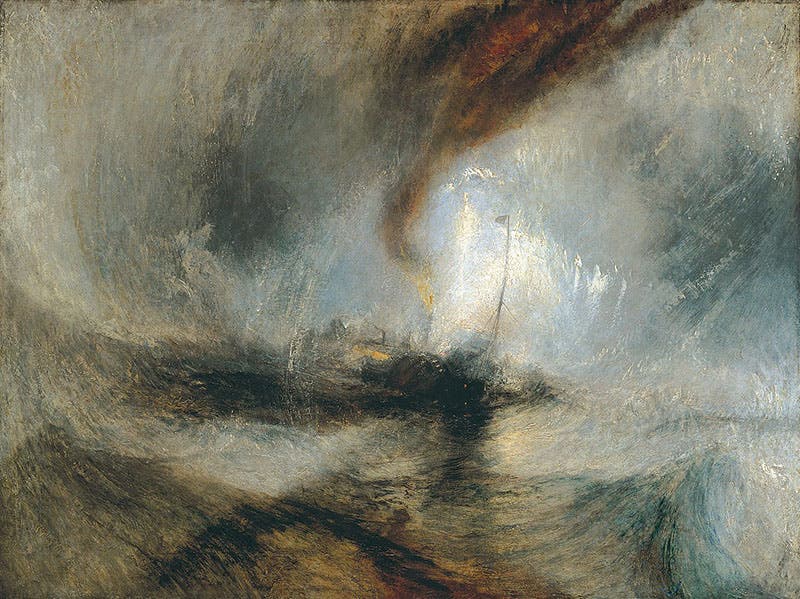

A third Turner painting we might look at is Snow Storm: Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth, painted in 1842 and now in Tate Britain (third image, just above). This shows a paddle-steamer, the Ariel, caught up in a storm; Turner claims he was actually on board at the time. The painting doesn't provide us much insight into contemporary technology, since it is in fact difficult to tell that there is a steamboat in there, amidst all that swirling paint. But it does provide some insight into Turner, because he certainly did have a different perspective on things. Eleven years earlier, Samuel Walters had painted the very same ship, The Paddle Steamer Ariel; the painting is now in the Royal Museums Greenwich (fourth image, just below).

This was how most of Turner's contemporaries saw and drew ships. And that is why Turner is so refreshing to us post-Impressionists.

A fourth Turner painting, a small watercolor usually called A Stormy Scene, portrays the cliffs and beach at Lyme Regis in Dorsetshire, depicting life that technology had not yet touched (fifth image, above). Lyme Regis was where young Mary Anning lived and prospected for fossils, and where she found the first skeletons of Ichthyosaurus and Plesiosaurus in the 1810s and 1820s. The painting shows no traces of fossils or fossil hunters, but it does have fishermen, and it does a wonderful job of evoking a seaside storm, with nary a steamship or a locomotive in sight, perhaps because it was painted in 1834, when the transformation of land and sea had just begun. The watercolor is in the Cincinnati Art Museum.

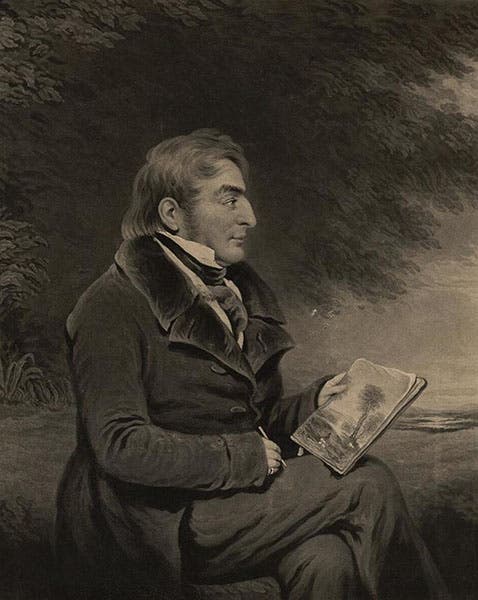

When you look up Turner on most biographical websites, such as Wikipedia, you will see a full-frontal self portrait of Turner, painted in 1799. I don’t much like it, and it hardly captures the Turner of forty years later who took on the railroads and steamboats. I prefer a mezzotint portrait of 1840, by Charles Turner (no relation), capturing Turner in the act of painting (sixth image, above). It would be nice if he were sketching for one of his technological paintings, but alas, he is drawing Mercury and Argus, in a landscape free of rain, steam, and speed.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.