Scientist of the Day - Henry Norris Russell

Linda Hall Library

Linda Hall Library

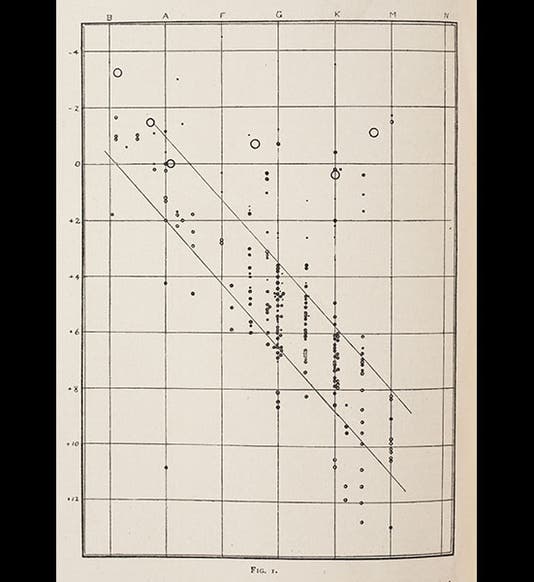

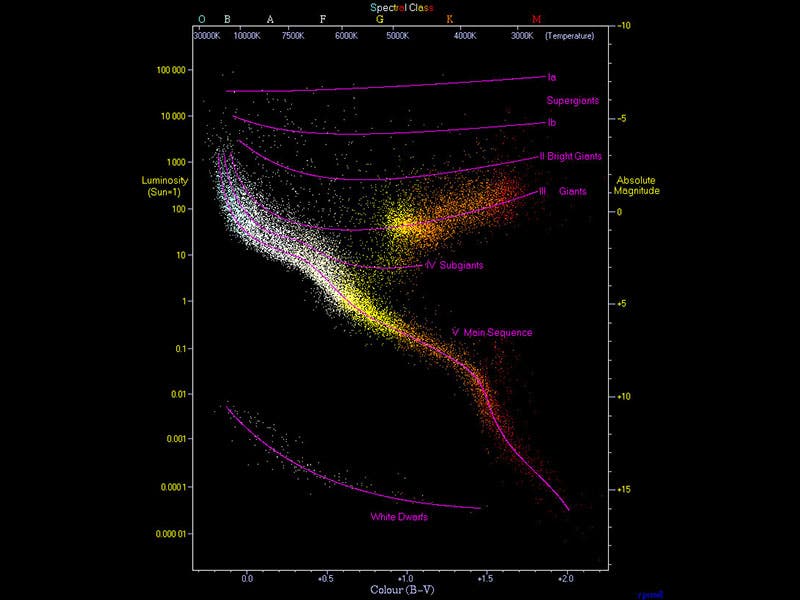

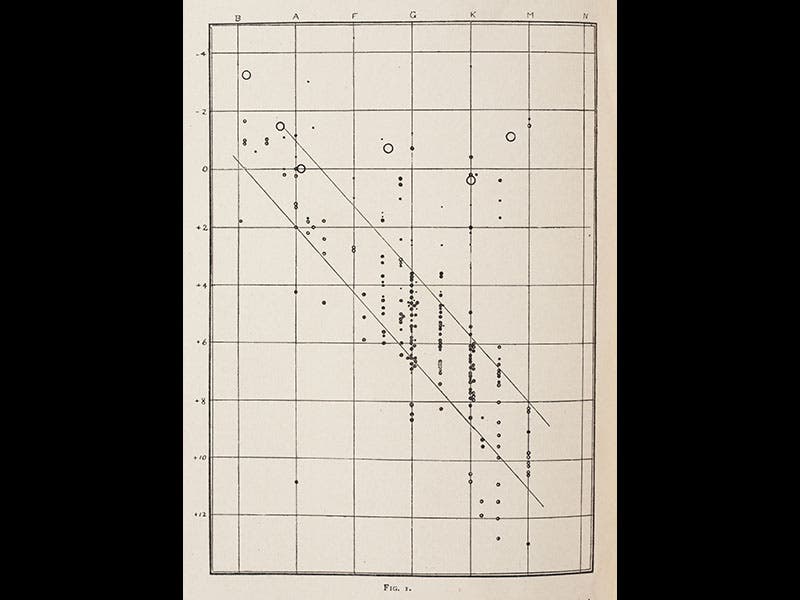

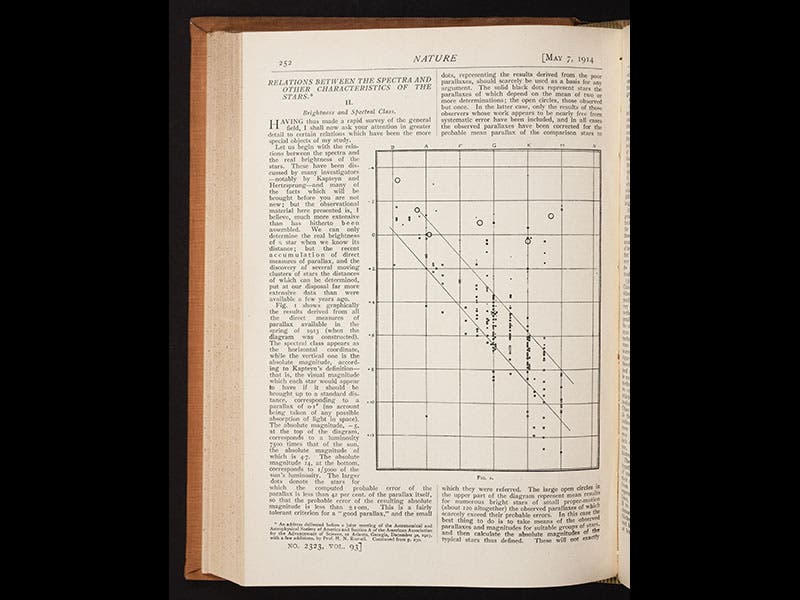

Henry Norris Russell, an American astronomer, was born Oct. 25, 1877. In the years before 1913, Russell spent his time comparing the luminosity and spectral type of stars. Luminosity--absolute brightness--was not a straightforward determination, since one has to know the distance to a star to determine its absolute brightness, but by 1913, the luminosity of several hundred stars had been reliably determined. The spectral type of thousands of stars was being sorted out by a team of women computers at Harvard College Observatory, headed up by Annie Jump Cannon, and they had worked out a classification system whereby hot white stars were classified as O or B stars, yellow stars were ranked A, F, or G, and cooler red stars were called K or M. Russell found that O and B stars tended to be very luminous, A, F, and G stars were of average luminosity, and K and M stars had very low luminosity, although there were some notable exceptions in this last group. If one graphed all the stars with known luminosity onto a chart where luminosity is the vertical coordinate and spectral type the horizontal coordinate, most of the stars line up on a reverse diagonal running rom upper left to lower right. Russell's diagram seemed to be a very handy scheme for organizing the stars, and he revealed it at a joint meeting of the American Astronomical Society and the American Association for the Advancement of Science on Dec. 30, 1913. The talk was then published in Nature in three successive issues beginning April 30, 1914; Russell's diagram first appeared in print in the May 7 issue (first and third images). It would prove to be an exceptionally versatile tool for discovering stars that are NOT normal, which means that they do not lie along the reverse diagonal (which would later be called the Main Sequence). It was subsequently learned that a Danish astronomer, Ejnar Hertzsprung, had come up with essentially the same diagram a few years before Russell, and although Hertzsprung studied a much smaller sample of stars that Russell, he was certainly on the right track. Consequently, the luminosity--spectral type diagram has come to be called a Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, or, more commonly, an H-R diagram. Any student of stellar astronomy encounters the H-R diagram very early in his or her studies.

Both Russell and Hertzsprung realized that there was an exceptional group of stars that are red but very luminous, and tend to cluster at the upper right of the H-R diagram, well above the main sequence. They would come to be known as red giant stars, and it was the H-R diagram that made their discovery possible. But it was Russell alone who identified another anomalous group, the white dwarfs. These are stars that are type O or B, and thus white-hot, but are not very luminous at all. In 1913, at the time of the first diagram, there was only one white dwarf known, and Russell had discovered it in 1910. The star was called 40 Eridani B, and you can see it as a single dot below the main sequence at the left on Russell's original diagram. Other white dwarfs, such as Sirius B, would soon be identified and added to H-R diagrams. A modern H-R diagram reveals how the number of known red giants and white dwarfs has grown since Russell’s day (fourth image).

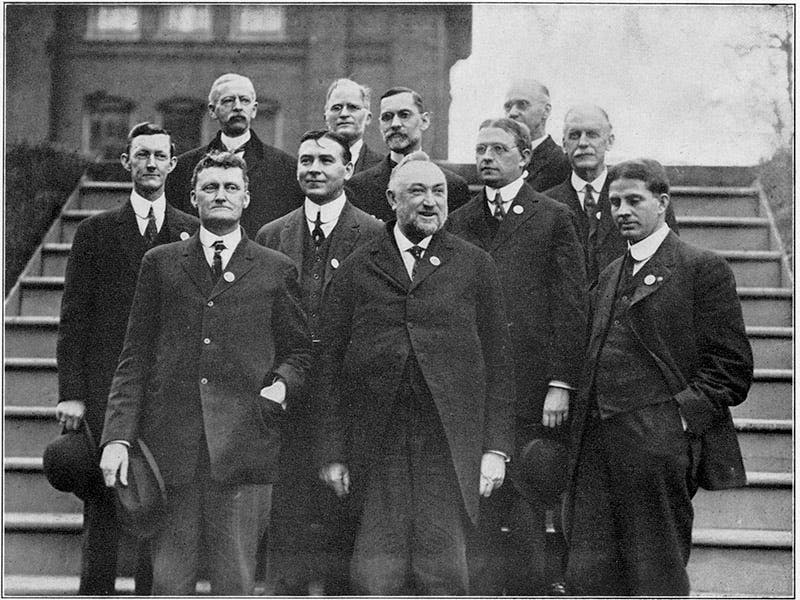

The group photo above (second image) was taken at the momentous Dec. 30, 1913 meeting at which Russell unveiled his diagram; Russell is the fourth from the right.

Russell spent his entire teaching career at Princeton University, working to unlock the secrets of the evolution of stars, and he is buried in the Princeton Cemetery, with a simple but handsome headstone (fifth image). It is surprising not to see an H-R diagram engraved somewhere on his monument.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.