Scientist of the Day - Henry Moseley

Henry Moseley, an English physicist, was born Nov. 23, 1887. In 1912, two English physicists (the Braggs, father and son) discovered that X-rays could be diffracted by (bounced off of) a crystal lattice of atoms, just like light is diffracted by engraved lines on a grating. These diffracted X-rays, it turned out, could provide information about atomic structure. Mosely followed up on this discovery. Working at Oxford, he learned how to get a variety of metals to emit X-rays, and how to diffract these from a crystal, and, most importantly, how to measure the wave-lengths of the X-rays. The only photo we have of Moseley shows him at work in his Oxford lab (first image).

Moseley discovered that the wave-lengths of the X-rays from his assortment of metals varied in step with something called Z, the atomic number. At that time, elements were identified by two quantities--atomic weight, and atomic number. Atomic weight was a real quantity, the mass of an atom compared to the mass of a hydrogen atom. Atomic number was an arbitrary quantity, the order of the elements as they appeared in the periodic table, but without any physical meaning (before Moseley).

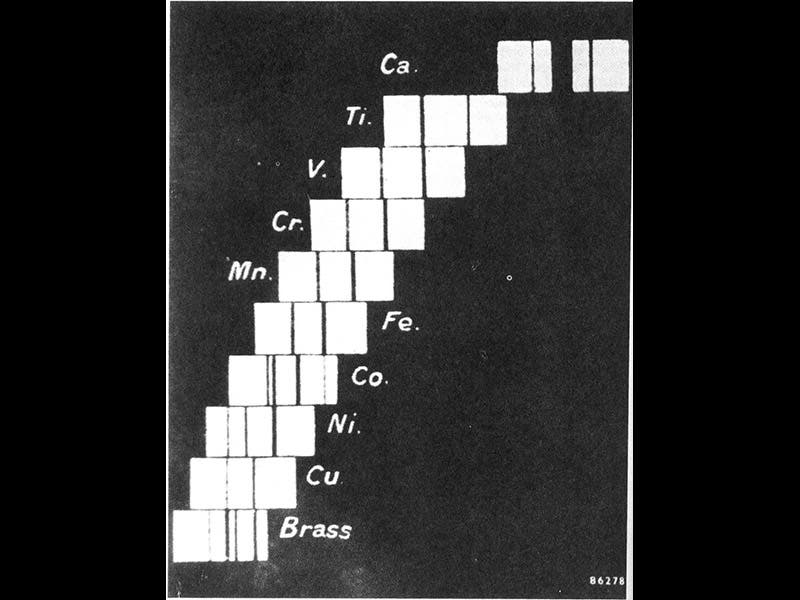

Moseley in papers in 1913 and 1914 demonstrated with little room for quibbling that the X-ray wavelengths of his elements varied according to the atomic number, and the atomic weight was irrelevant. Moseley argued that atomic number is a better indicator of an element's chemical properties than atomic weight. In fact, he even reversed the order of two elements in the periodic table--nickel (atomic weight 58) was customarily placed ahead of cobalt (59), but Moseley showed that cobalt has an atomic number of 27 and should be placed ahead of nickel (atomic number 28). In this chart published in his paper of 1914, where elements are ordered by their X-ray frequencies, the result is also an ordering by atomic number (second image).

Once the proton was discovered in 1919, it was realized that Moseley's atomic number indicated the number of protons in the nucleus, making the atomic number indeed a key property of atoms. Moseley never witnessed the success of his discovery, because he was killed in the early years of World War I, shot through the head in 1915 by a Turkish soldier during the battle of Gallipoli. He was 27 years old. It is generally believed that had Moseley lived just one more year, he would almost certainly have been awarded a Nobel Prize in 1916 for his discovery of the physical basis of atomic number. Since Nobel prizes are given only to living recipients, that possibility died with Mosely at Gallipoli. The Nobel Prize in Physics in 1916 was not awarded at all.

There is a blue plaque at Oxford, commemorating Moseley and his work (third image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.