Scientist of the Day - Henry Fitz

Henry Fitz, an American telescope maker, was born Dec. 31, 1808. Fitz was the first professional telescope maker in the United States, which is to say that for the last 15 years of his life (he died in 1863), he was able to earn a living by making and selling telescopes to newly-founded observatories and wealthy amateurs. He was trained as a locksmith, but once he saw his first refracting telescope, he was hooked, and locksmithing was just a way to support himself while he learned the craft of lens grinding. At the time he began, a 6" refractor (meaning a lens-based telescope with a glass objective that is 6" across) was as large a telescope as you could find in the U.S., and all of those came from England or Germany. Fitz made several 6" refractors in 1849 and 1851, and these had the resolution of the finest German imports.

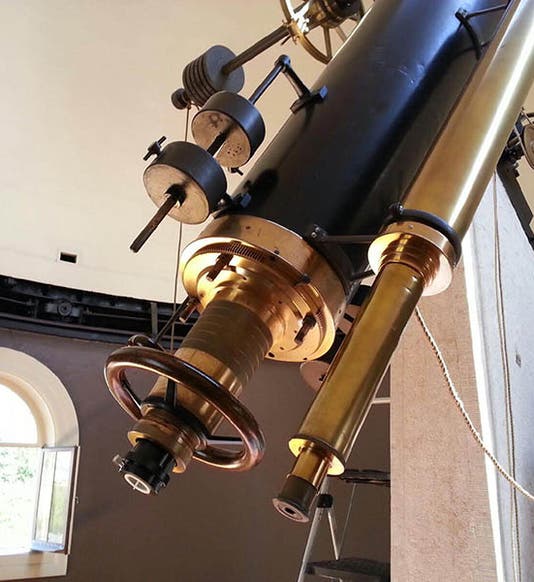

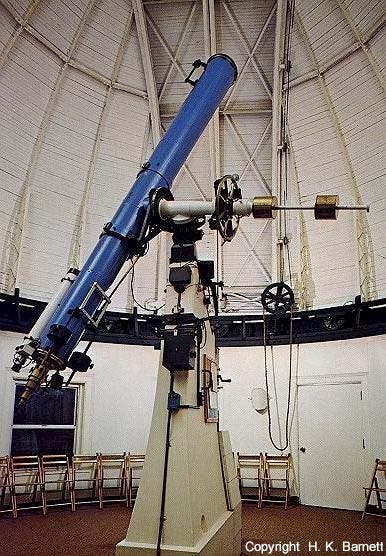

As observatories sprang up in the United States, Fitz began to get commissions. He made a 12" telescope for a private customer in 1852 that eventually ended up at Wellesley College; a 10" refractor for the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1856; a 12 ¼" instrument for Detroit Observatory in Ann Arbor in 1857 (first image); a 12 ½" telescope for Vassar College in 1861; and a 13" instrument for Allegheny Observatory in Pittsburgh, also in 1861 (second image). Four of Fitz’s telescopes were the largest American-made refractors in the world at the time they were built.

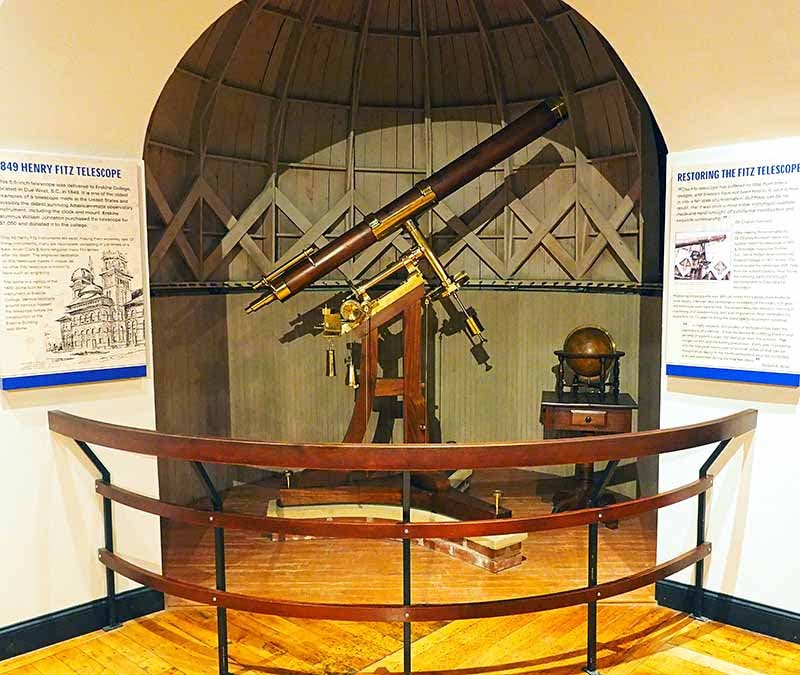

A number of Fitz's refractors survive, and several are still in use – the ones at Wellesley, Ann Arbor, and Pittsburgh can be seen on their original mounts right now. The Vassar instrument was given to the Smithsonian Institution in 1959 and can be seen on display at the National Museum of American History (third image). The instrument that Fitz made for Erskine College in South Carolina – a 5.6" refractor – was discovered disassembled and in storage in the 1980s by an antique telescope collector, who restored the instrument; it may now be seen in the South Carolina State Museum (fourth image). It is the oldest American-made refractor to be found anywhere.

Unfortunately for his reputation, Fitz’s telescopes were eclipsed in the 1860s by refractors made by Alvin Clark & Sons of Cambridge, Mass. In 1863, Alvan Clark made a refractor of 18.5" aperture, and over the course of several decades, he and his sons fabricated objectives of 26”, 30”, 36”, and 40", for such observatories as the U.S. Naval Observatory, Lick Observatory, and Yerkes Observatory. Fitz's largest lens of 16" was dwarfed by the 40" Yerkes lenses. In the Age of the Clark Refractor, nearly everyone forgot about Henry Fitz. It didn't help that several of Fitz’s lenses, those at Vassar, Wellesley (eventually), and Allegheny, were refigured by Clark at the request of their owners. The era of the Fitz telescope was clearly important; you would not have had Clark telescopes without trail-blazer Henry Fitz. But while every amateur astronomer has heard of Clark telescopes; very few know anything about the refractors of Henry Fitz. He deserves more recognition.

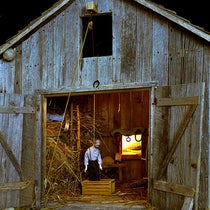

For a while, you could learn about Fitz in a Smithsonian exhibition in Washington, D.C. In 1959, about the time the Smithsonian acquired the Vassar refractor built by Fitz, they also acquired many objects from Fitz's workshop, which were in the possession of Fitz's granddaughter. From these materials, Fitz's workshop was re-assembled and put on display in the Arts and Industries Building on the National Mall (fifth image). However, in 2004, the building, one of the oldest on the Mall, was closed for safety reasons, and while it has now been reopened, I do not believe the Fitz workshop display still exists.

Fitz was also a pioneer in early American photography, mastering the daguerreotype almost as soon as it was invented in 1839. One of his earliest daguerreotypes is a self-portrait, 1839, held by the National Museum of American History (sixth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.