Scientist of the Day - Heber Curtis

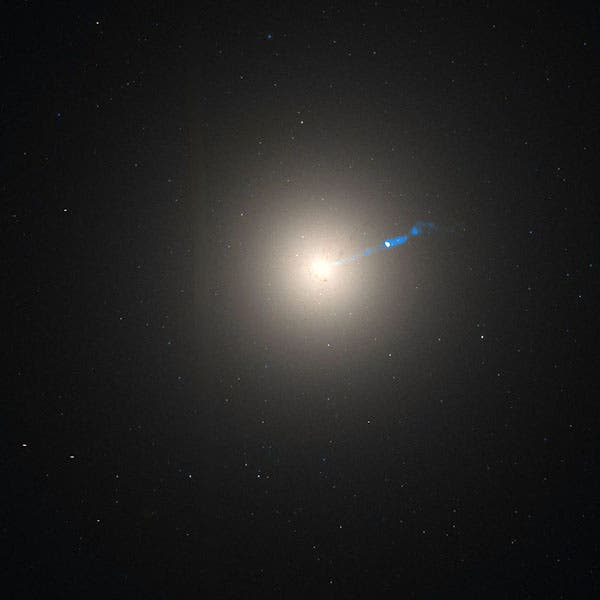

Heber Doust Curtis, an American astronomer, was born June 27, 1872. Curtis spent much of his career at the Lick Observatory in California, before moving to the Allegheny Observatory in 1920, and eventually to the University of Michigan. His two passions appear to have been solar eclipses - he journeyed far and wide to observe 11 of them - and nebulae, spiral or any other shape. In 1918, he published a study of 762 nebulae that he had photographed with the Crossley reflector at the Lick Observatory. Concerning one of those nebulae, which he referred to as N.G.C. 4486, and which we generally call M87, he noted that this roundish nebula had a “curious straight ray” that seemed to come right out of the center of the nebula (second image). He obviously saw this on a photograph, since it is impossible to detect with the naked eye, but he did not publish the photograph along with his paper, and I have been unable to determine if it was ever published. It would be nice to find, because Curtis's “straight ray" turns out to be a cosmic jet of incredible size, emitted from the core of M87, which we now know harbors an immense black hole. Until we can find the first photograph of M87's jet, we show you one of the latest, taken by the Hubble Space Telescope (third image). The jet is 1500 parsecs long, which means that even if you were travelling at Warp One, trekkies, it would take you almost 5000 years to navigate its length.

Curtis's expertise on nebulae was the reason why he was invited to participate in a debate in 1920 on "The size of the universe and the nature of the spiral nebulae." The occasion was the annual meeting of the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., and the debate was prompted by the recent claims of Harlow Shapley, an astronomer from Mt. Wilson Observatory who would soon move to Harvard. Shapley had just discovered the great size of our Galaxy, which he calculated at 300,000 light-years across, and Shapley concluded that everything else one could see, including the mysterious spiral nebulae, must be within our own Galaxy. Shapley maintained this position at what has been called the "Great Debate," which took place on Apr. 26, 1920. Curtis, on the other hand, stuck to the conventional figure for the size of our Galaxy, 30,000 light-years (rejecting Shapley's new figure), and argued that the spiral nebulae must be external galaxies, “island universes,” comparable to our Milky Way Galaxy in size and number of stars. As often happens in such confrontations, each man was partly right and partly wrong. Shapley was right about the great size of our Galaxy (although it is closer to 100,000 light-years across). Curtis was right about the spirals being galaxies outside our own Galaxy. Interestingly, the Great Debate became notable as a cosmological watershed only in hindsight; at the time, it received little notice in scientific literature or the popular press. It took Edwin Hubble to make the Great Debate famous, almost five years later, when he measured the distance to the Andromeda nebula, and found it to be a galaxy just like our own, nearly 2 million light-years away, and thus far outside the Milky Way Galaxy.

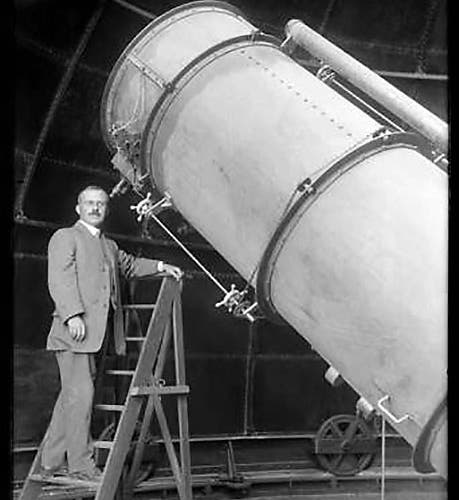

The photograph of Curtis (first image) shows him standing next to the 36” Crossley reflector, which the Lick Observatory acquired in 1895 and completely rebuilt, and which Curtis used for his nebulae studies. The Crossley had been commissioned in 1879 by A.A. Common and was used by him to take the famous photograph of the Great Nebula in Orion in 1883 that you can see at the link.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.

![The section of Curtis’s catalog of nebulae where he notes that [N.G.C.] 4486 has a straight line coming out of the nucleus, from Publications of the Lick Observatory, 1918 (Linda Hall Library)](https://assets-us-01.kc-usercontent.com:443/9dd25524-761a-000d-d79f-86a5086d4774/ab81917b-534f-4aa5-a7cd-b05d80c98b9b/curtis2.jpg?w=800&h=250&auto=format&q=75&fit=crop)