Scientist of the Day - Gustav Holst

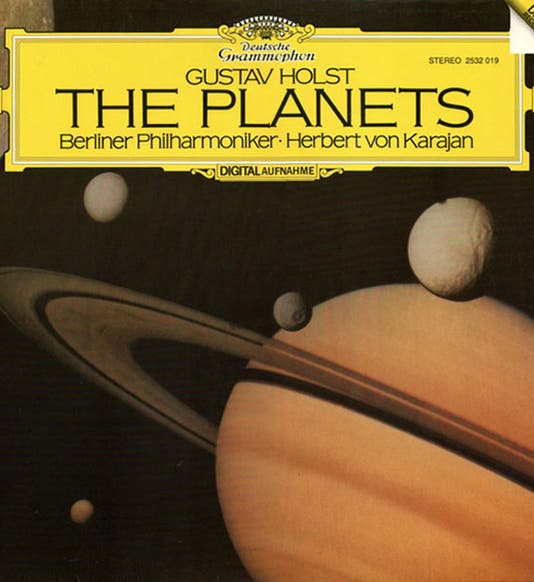

Gustav Holst, an English composer, was born Sep. 21, 1874. Holst was a prolific composer of music, but his most familiar piece seems quite appropriate for a scientific anniversary series. The Planets, a suite for orchestra, was composed in 1914-16, given its first private performance in 1918, and presented to the public in 1920. It contains 7 movements, one for each planet, the earth being excluded, and Pluto being yet undiscovered. The motif for each movement was determined by each planet's astrological character, rather than its physical features, which somewhat threatens its status as a bridge between music and science, but we are tolerant here. Each movement has a planetary title and a subtitle, such as "Mars, the Bringer of War", and the order of the movements is odd, proceeding, after Mars, to: Venus (Peace), Mercury (Winged Messenger), Jupiter (Jollity), Saturn (Old Age), Uranus (the Magician), and Neptune (the Mystic). The opening movement, “Mars”, may be the most familiar—here is a recording by The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by Charles Mackerras. It suggests that Holst might well have heard Igor Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring when it was first performed in London in 1913 and perhaps Arnold Schoenberg as well.

The last movement, “Neptune the Mystic”, is noteworthy because of its ending, involving a women's chorus. In the original performances of the 1920s, the chorus sang from an off-stage room, and for the final bars, the door was slowly closed, producing (supposedly) the first fade-out in classical music history. In this version, the chorus first appears about the 4:45 mark and fades into inaudibility about 2 minutes later.

If anyone wants to listen to the entire piece in order, there are several versions on YouTube; here is the one most watched, featuring Andrè Previn and the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. If you don’t want to look at Holst’s face for 49 minutes, this one by the National Philharmonic of Warsaw was recorded live and shows lots of strings, horns, and bassoons in action.

Holst never wrote another piece like The Planets and apparently very much regretted having made this one exception, since it was by far his most popular composition with the public, and he did not want to be remembered for a mere piece of program music. He probably has a lot of company in the "Musical Regrets" section of Heaven, where he is perhaps joined by Amilcare Ponchielli and Paul Dukas, who no doubt wish that Walt Disney had chosen some other means besides Fantasia (1940) to introduce classical music to the masses.

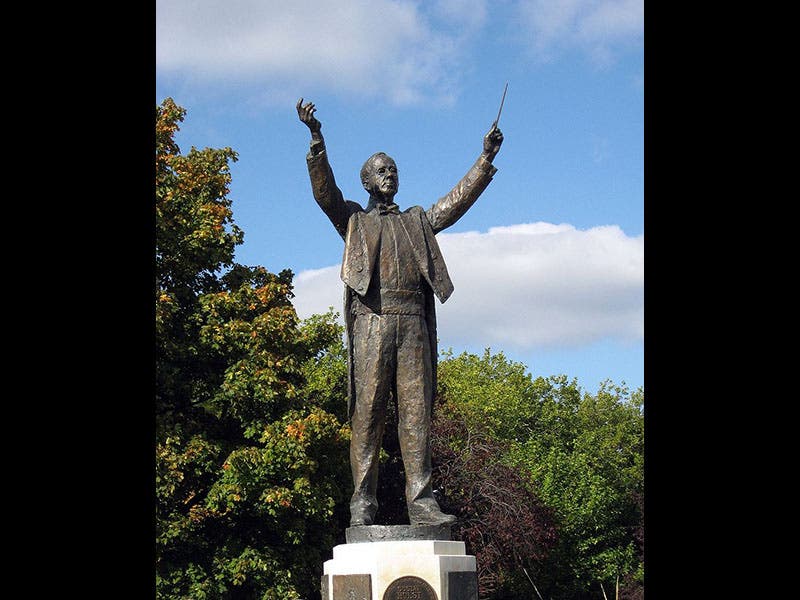

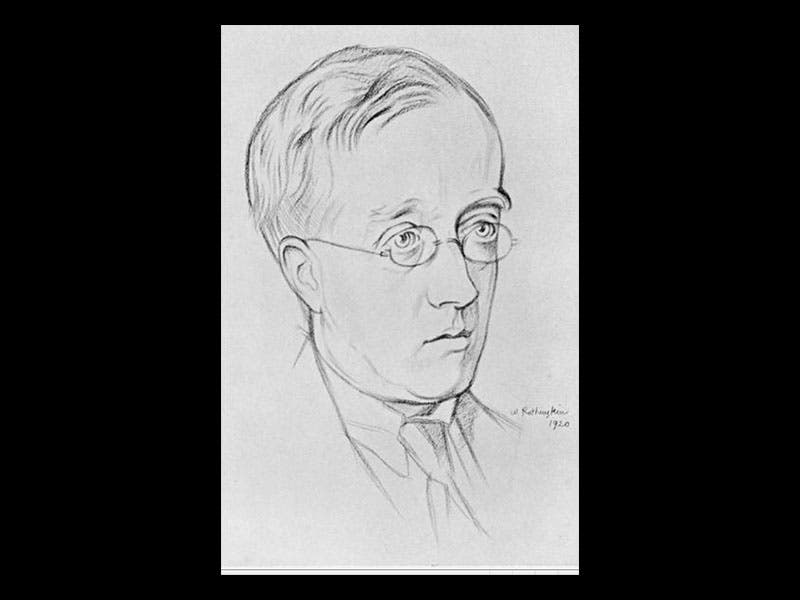

There is a statue of Holst conducting (left-handed) in his home town of Cheltenham (second image), and we also include a sensitive pencil portrait made by William Rothenstein in 1920 (third image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.