Scientist of the Day - Govard Bidloo

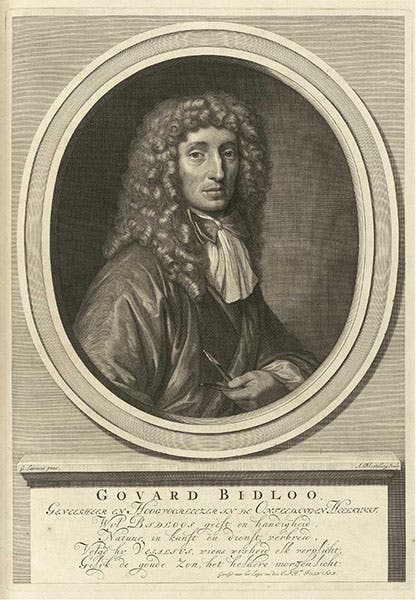

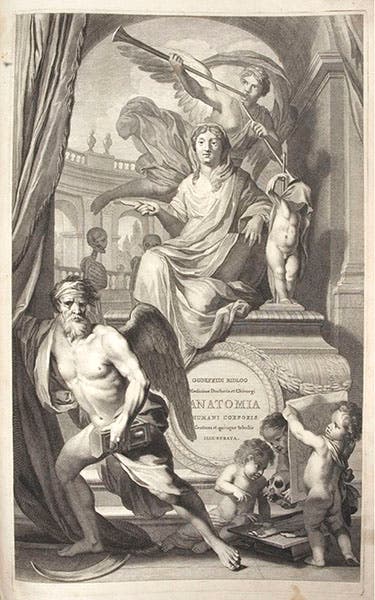

Govard Bidloo, a Dutch physician and anatomist, was born Mar. 12, 1649, in Amsterdam (second image). Bidloo studied anatomy in Amsterdam with a very young Frederik Ruysch, who would create his marvelous anatomical tableaux decades later. In 1685, when Bidloo himself was only three years out of med school, he published an illustrated book of human anatomy, Anatomia humani corporis. Bidloo wrote the Latin text, and a noted artist, Gerard de Lairesse, was commissioned to provide the drawings for 105 large engraved plates.

There were many anatomical atlases published in the aftermath of Andreas Vesalius’ De humani corporis fabrica, which issued from the presses in Basel in 1543 and took the anatomical world by storm. We do not collect works in medicine or human anatomy, but we do have a first edition of Vesalius’s folio, because of its importance in the history of scientific illustration. Every illustrated anatomy book published after De Fabrica – and there must have been at least 50 of them between 1543 and 1685 – was under the inexorable spell of Vesalius. The plates, whether engraved or woodcut, looked just like those of Vesalius, even the ones that were brand new, so that if you opened up all those atlases and put them on display, the casual viewer might well think they were all variants of the same book – which, in many ways, they were.

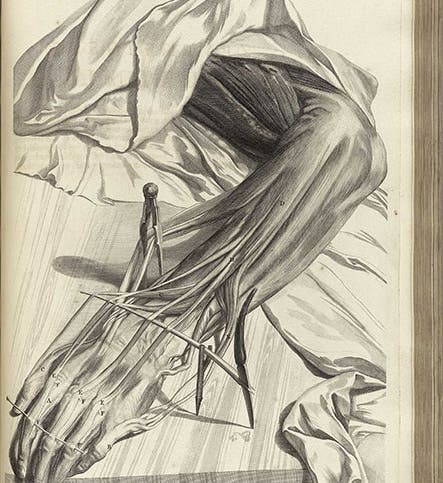

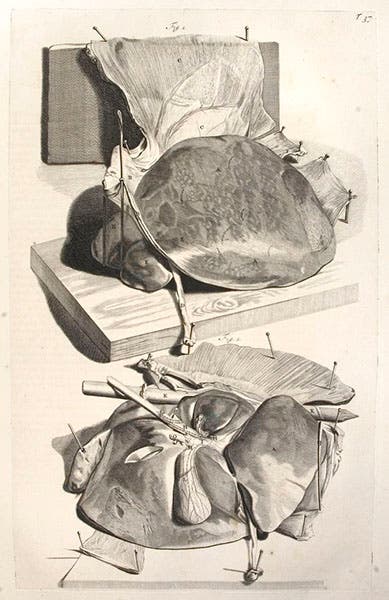

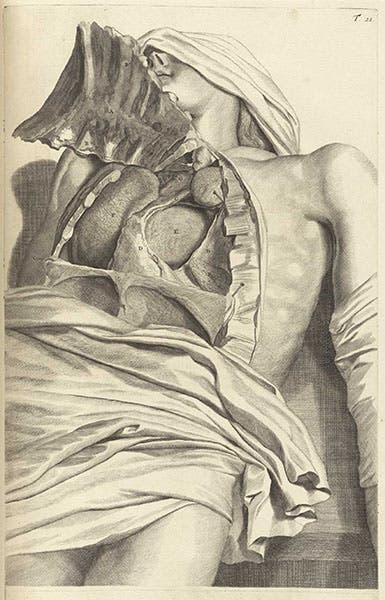

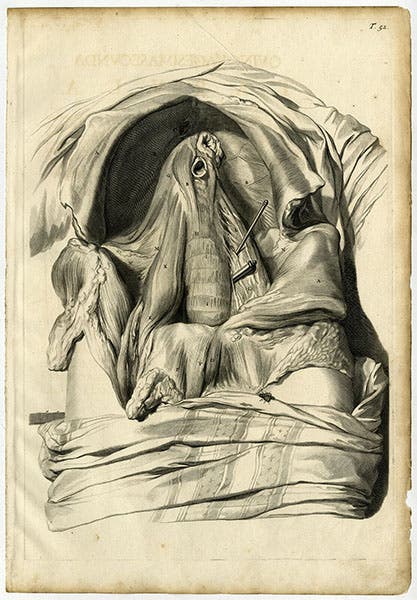

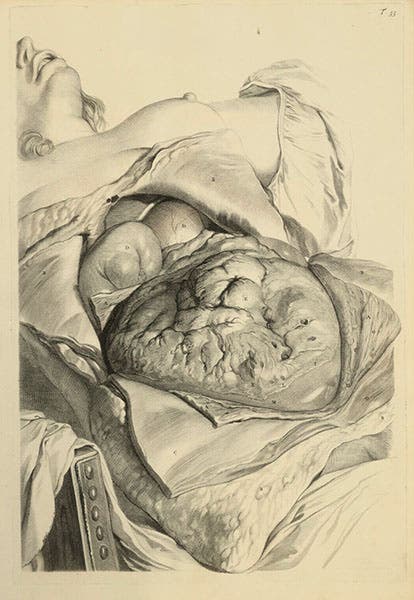

But Bidloo and de Lairesse broke the mold. Their plates in Bidloo’s Anatomia are utterly unlike those of Vesalius. Whereas the Vesalius plates were in classical poses, framed against landscape backgrounds, and so "clean" that you easily forget that they depict dissected bodies, the Bidloo plates are utterly realistic, so much so that you sometimes have to turn away from their frankness. They really do look like dissected bodies. Several of the plates even include engraved flies that you instinctively try to brush away. Leafing through that volume, which I have done, is a brutal experience.

I have always admired the Bidloo atlas, because it demonstrates how hard it is to break with tradition – indeed, no one even realized the pervasiveness of the Vesalian tradition until Bidloo and de Lairesse stood completely outside of it. And once Bidloo and de Lairesse showed how to present human anatomy differently, no one went back. Except for the odd Vesalian illustration in such books as the great French Encyclopedie, the Vesalian school died in 1685, as rapidly as it had been born in 1543. We often speak of the Vesalian revolution of 1543. We ought to speak as well of the Bidloo revolution of 1685.

I wanted to showcase here the Bidloo copy at Vassar College, which they bought for their millionth volume in 2012, an inspired choice (rivaling, we like to think, our selection of Claude Perrault’s Mémoires pour servir a l’histoire naturelle des animaux (1676) for our millionth volume in 1996). But for some reason, Vassar has restricted access to the plates in their copy, so we cannot reproduce them. We show instead images from the copies in the Lilly Library at Indiana University and the National Library of Medicine, which has a 1690 edition in Dutch, but with the same plates as the 1685 edition. Curiously, the plates that the NLM makes available on their website are the less graphically realistic ones. Possibly the same elected officials who got upset when Pioneer 10 and 11 carried images of nude humans into space, warned government institutions not to put up gruesome pictures on their websites. We had to go to eBay to find two of the more dramatic plates (sixth and seventh images).

It does not seem to be known who played the greater role in the Bidloo revolution, Bidloo or de Lairesse. Vesalius gets the credit for his revolution, probably because we don’t know who his artist was. In this case, the credit should probably be shared. When de Lairesse’s birthday rolls around next Sept. 11, perhaps we can look more into his side of the story. Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor emeritus, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.