Scientist of the Day - Gouverneur Warren

Gouverneur Kemble Warren, an American explorer and cartographer, was born Jan. 8, 1830. Warren was a topographical engineer, a member of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers that was established in 1838 and was largely responsible for exploring and mapping the American West before the Civil War. Warren came out of West Point in 1850 with his guns smoking. A dashing, likeable young lieutenant, he quickly found himself out west and a member of exploratory expeditions that went up the Missouri to Montana, across the Dakotas and Nebraska on foot (hazardous Sioux country), and into the Rockies. He was too late for the Pacific Railroad Surveys of 1853-56, where many topographical engineers made their mark (see for example our essays on Edward Beckwith and Amiel Whipple), but Warren quickly realized that, with all this exploration going on, what was really needed was a map that put all of the geographic data brought back by the surveys into a visual context. He read all the reports from the railroad surveys, as well as the narratives of every expedition that had ventured west, from Lewis and Clark and Zebulon Pike to the multiple trips of Stephen Long and John Fremont. When visiting the trading posts at Fort Union, Fort Benton, and Fort Kearny, he sought out the fur traders and mountain men and encouraged them to make him hand-drawn maps of the territories they knew so well. And then Warren set to making a Map of the Territory of the United States from the Mississippi to the Pacific Ocean, and a companion Memoir to accompany the Map.

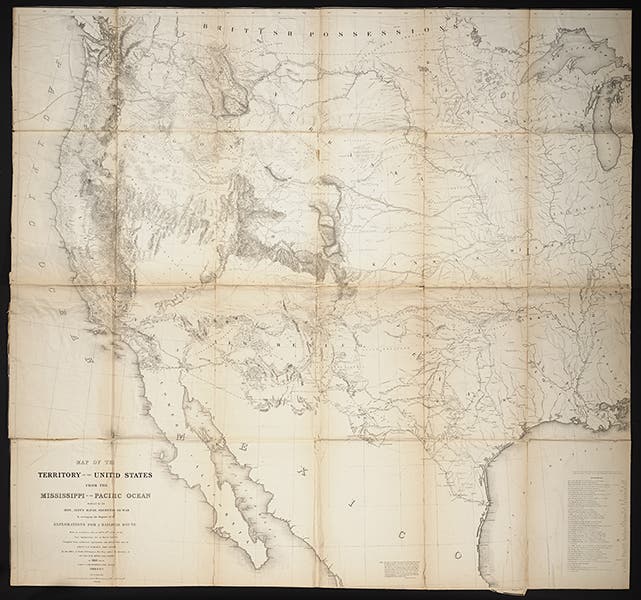

Map of the Territory of the United States, by G.K. Warren, 1861 (Linda Hall Library)

The map seems to have been completed in 1857, and the Memoir in 1859, but they did not appear in print until 1861, in volume XI of the 13-volume Pacific Railroad Reports. The map is over four feet square and has to be folded and refolded to fit into the back of the printed volume. And it shows just what Warren claimed it would show – the entire American West, from the Mississippi to the western sea (second image).

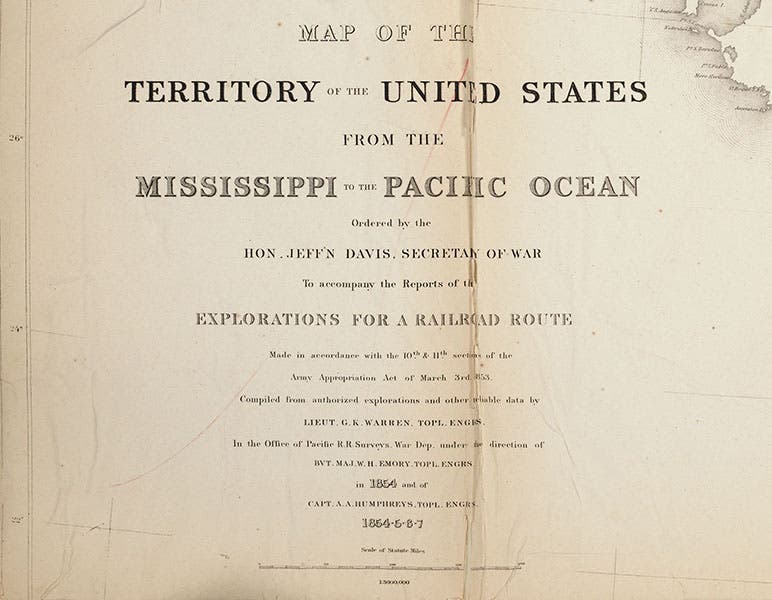

Title and publishing information, detail of G.K. Warren, Map of the Territory of the United States, 1861 (Linda Hall Library)

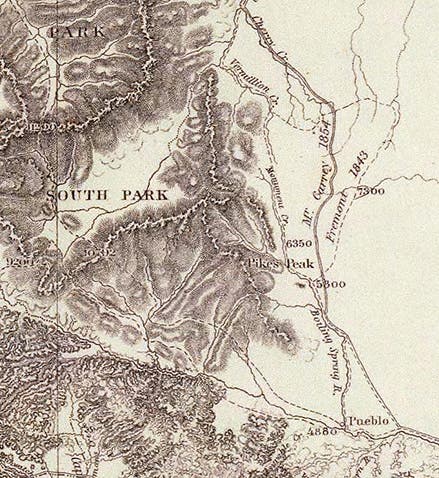

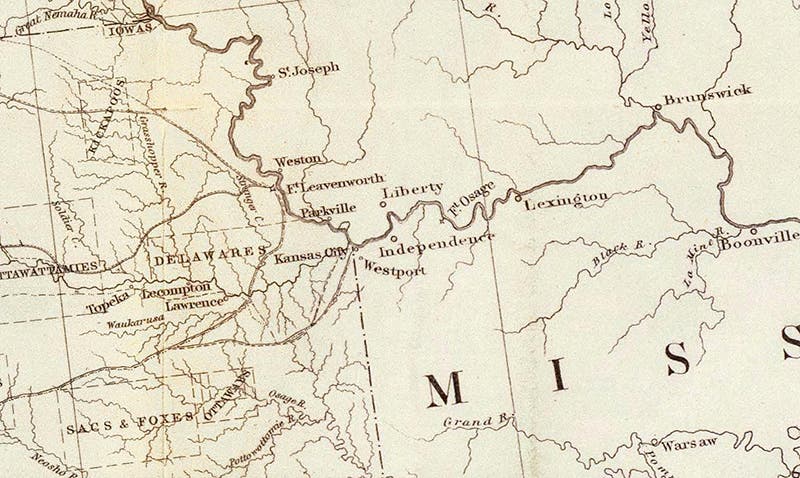

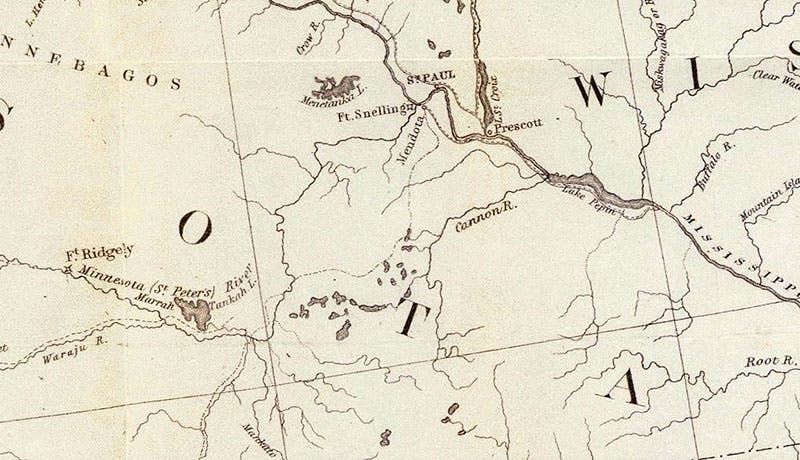

We have removed our copy from its volume and it is now stored flat in a map case. Still, it is a bear to photograph. The image of the complete map shows our copy, as does the detail of the title section (third image), but the super-details are taken from an online map owned by David Rumsey which is fully zoomable and which you might like to examine further. The details we include show the Colorado Rockies and Pike's Peak (first image); the area around us at the Library, denoting Indepencence, Westport, and Kansas City (fourth image); and the valley of the Minnesota River before it empties into the Mississippi river at St. Paul (fifth image).

We selected the last region because of a prescient observation later made by Warren, in 1868. He explored the area several times, before and after the War, and he was perplexed by the fact that the Minnesota River, which is barely a river at all, flows down the center of a valley that is more than 5 miles wide.

Since such an insignificant river could hardly have sculpted such a sizable valley, Warren proposed that during the Ice Age, there must have been some sort of a massive lake up north that was constrained by a glacial dam, and when the dam broke, the flow of water formed an immense river that drained the lake into the Mississippi River and carved out the Minnesota River valley. The present day river is its remnant. Modern day glaciologists believe that Warren was basically right. The formerly existing Pleistocene lake, which covered much of northern Minnesota, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, has been named Lake Agassiz, and the river that drained it, the precursor to the Minnesota River, has been named the Glacial River Warren, in honor of our Scientist of the Day.

We displayed the Warren map in our 2004 exhibition, Science Goes West, which is not available online.

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.