Scientist of the Day - Georges Méliès

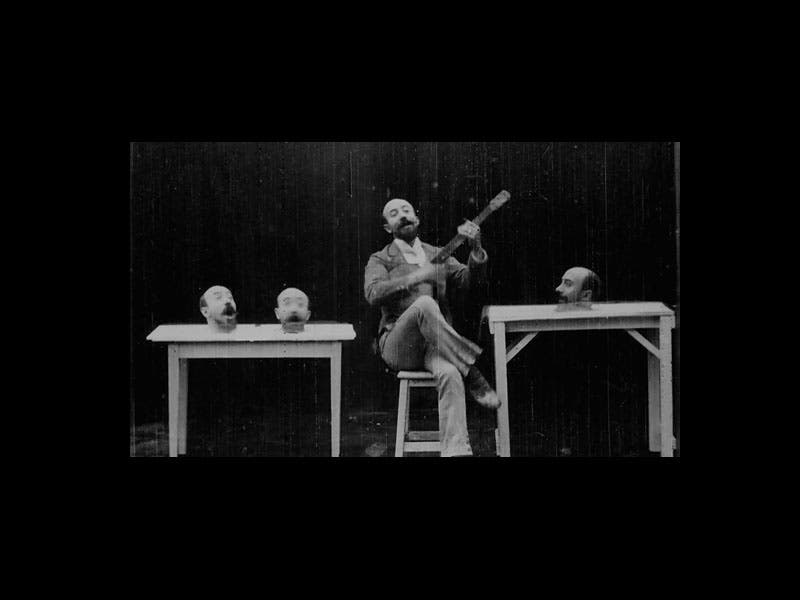

Georges Méliès, a French filmmaker, was born Dec. 8, 1861. Méliès started out as a magician and illusionist, but when he saw a Lumière Brothers cinematograph in 1895, he took an immediate detour into the greatest illusion of them all: film. Unable to buy a cinematograph from the Lumière firm, he built his own. He began making movies in 1896 and eventually made over 500 of them. They are short films, 15 minutes or less, usually much less, but in those long strips of celluloid, Melies invented and employed virtually every cinematic trick that it was possible to devise at the turn of the century: splicing, dissolves, multiple exposures. For example, the film Un homme de têtes (A Man of Heads, 1898) shows Méliès himself serenading the viewer with three additional heads singing along on their individual tables (second image). You can view the entire film here; it is a delightful one minute long:

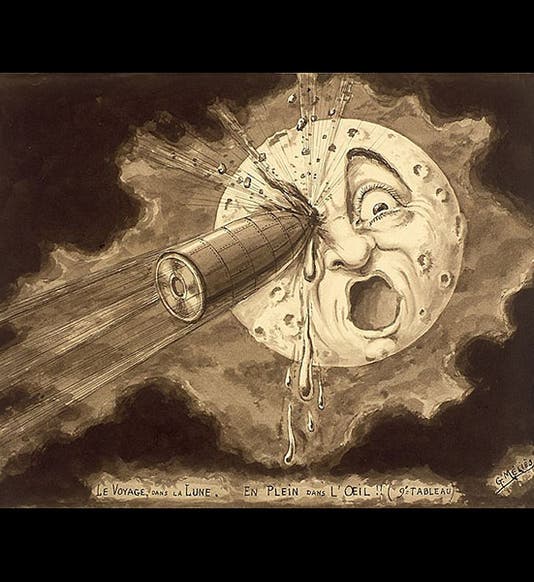

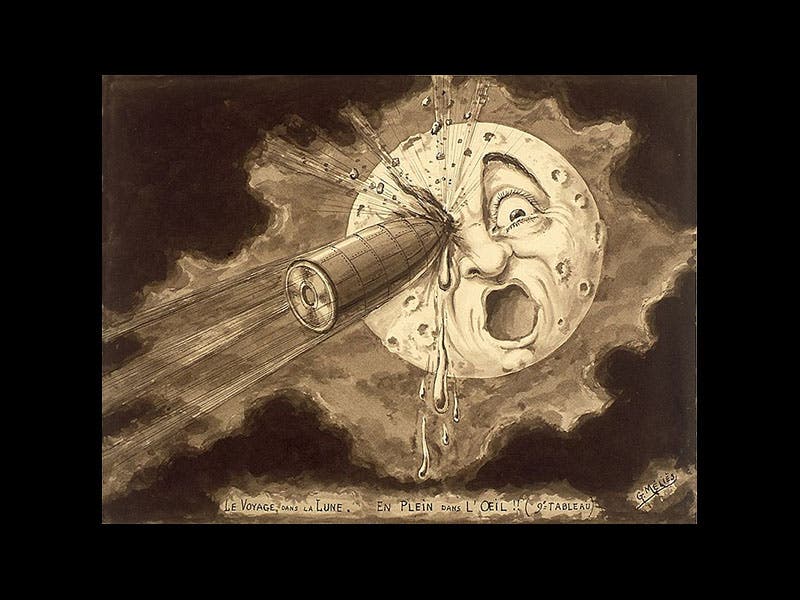

Méliès earns a place in this column because of two particular films he produced: Le voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon, 1902), and Voyage à travers l'impossible (The Impossible Voyage, 1904). A Trip to the Moon is the more notable, because it was first, and therefore was the first science fiction film ever made (The Impossible Voyage was the second). The plot, such as there is, was drawn from Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon, but in fact the film is basically just a sequence of special effects cooked up by Méliès in his little cinematic studio. A group of men, led by Professor Barbenfouillis (played by Méliès himself) decide to go to the moon; they build a bullet-like capsule, which is escorted to a long cannon-like launching tube by a bevy of young coquettes, and then propelled to the Moon. The signature moment of the film comes when the capsule impacts the moon, striking the right eye of the Man in the Moon (fourth image). There are many versions of the entire 15-minute film on YouTube, some are in black-and-white, some in color (Méliès actually produced his own colored versions of his films, hand-painting the color onto each of the thousands of frames in the film). Nearly all the restorations have added scores, since the original movie was silent. I chose one with the least offensive music, but you can certainly find others that you might prefer. In the linked version, the lunar launch sequence begins at 5:20 and the lunar impact at 7:19.

Amazingly, Méliès’ original drawing for the iconic projectile-in-the-eye image survives (first image). If it looks familiar, you might be recalling the film Hugo (2011), directed by Martin Scorsese. The movie was based on a book by Brian Selznick, The Invention of Hugo Cabret (2007). In the film, there is a dramatic sequence in which an automaton, which has been rebuilt by the boy Hugo, is coaxed back to "life" and produces a drawing, which is none other than Méliès’ “Projectile hitting the Moon.” The automaton then adds the signature “Méliès” to the bottom of the drawing, which is the first clue that the grumpy toy-shop proprietor in the film, Papa Georges Méliès, had formerly been a famous cinematic director. Both the film and the book are extended homages to Méliès, who spent the last several decades of his life in relative poverty, forgotten by the cinematic industry he helped create, until his importance was belatedly recognized and he was finally honored for his contributions. The final scene of Hugo reconstructs one such tribute. Ben Kingsley’s portrayal of Méliès is uncanny.

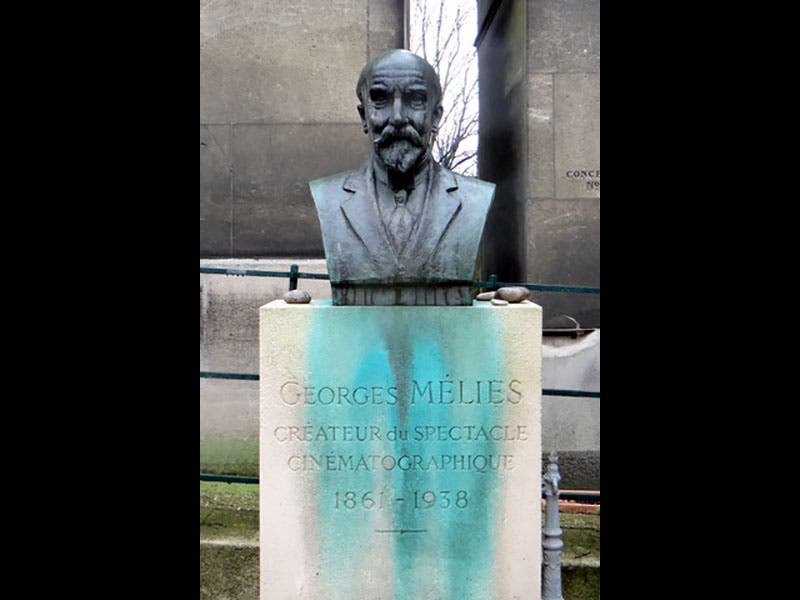

Méliès was buried at Pere Lachaise cemetery in Paris, where there stands a bust in his honor (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.