Scientist of the Day - Frederick Soddy

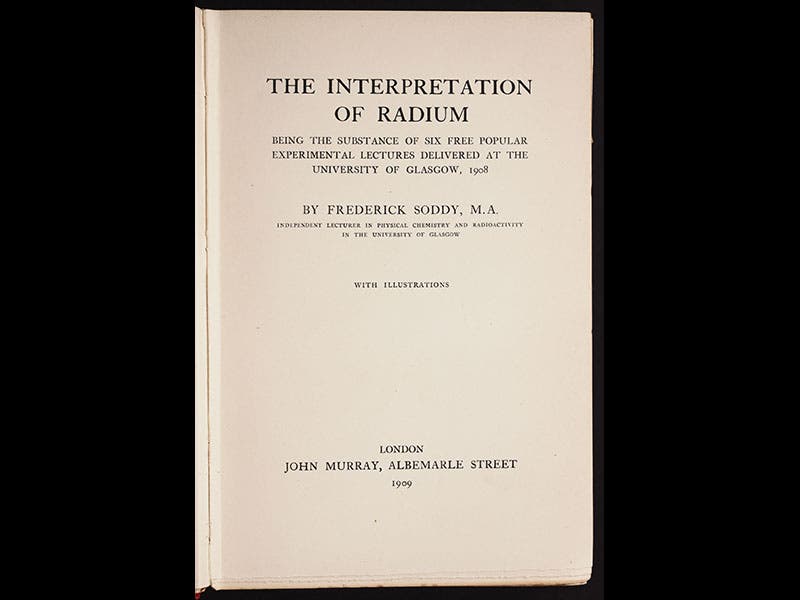

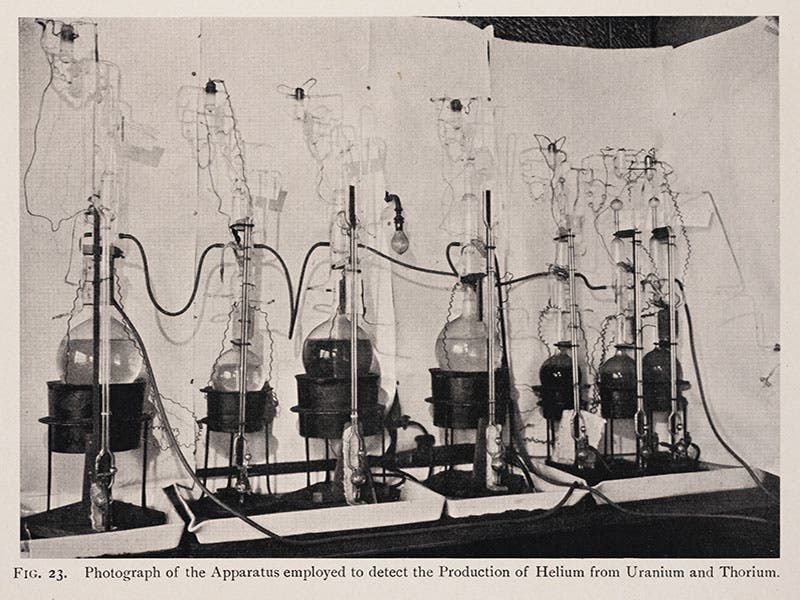

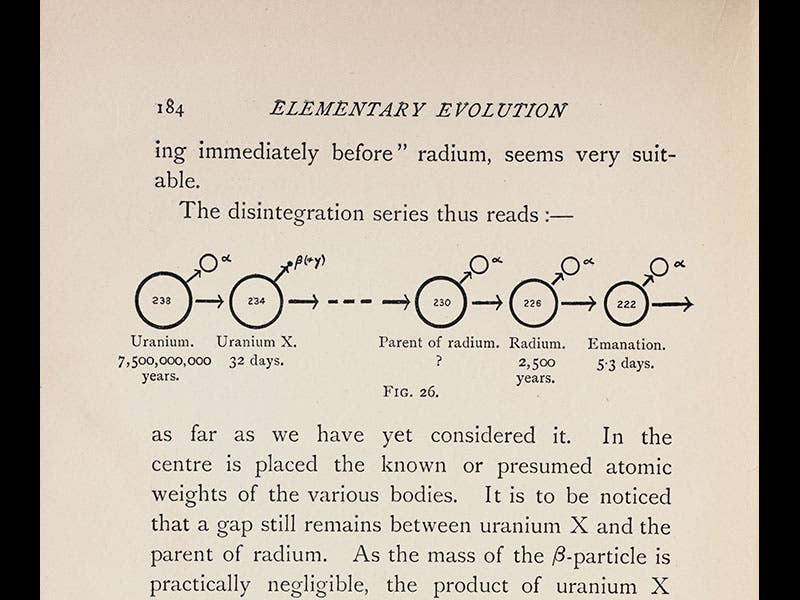

Frederick Soddy, an English chemist, was born Sep. 2, 1877, just one day after yesterday's Scientist of the Day, Francis Aston, another English chemist. In 1900, Soddy, who was then teaching at McGill University in Canada, was shanghaied by Ernest Rutherford to investigate the radioactivity of thorium (this was just 2 years after the Curies had discovered radium). It was Soddy who discovered that radium is a product of the disintegration of uranium (third image), and that radioactive decay produces helium gas as a byproduct (because the emitted alpha particles, which are basically helium ions, will turn into helium gas when they acquire electrons). Soddy also determined that radioactive decay produces almost a million times more energy than a chemical reaction. When this appeared in his book, The Interpretation of Radium (1909), it was read by H. G. Wells, who was inspired to write The World Set Free (1914), the first book to suggest the potential for humankind of nuclear energy.

Since yesterday we celebrated the birthday of Francis Aston, who first identified many isotopes, it seems appropriate to mention that Soddy coined the word “isotope” in 1913, before any had even been isolated. He realized that there are some 40 different elements that had been identified as being produced by radioactive decay, but that there were only 11 places on the periodic table between uranium and lead. Hence, some of these elements had to be in the "same place" (which is what "isotope” means). "For his contributions to our knowledge of the chemistry of radioactive substances, and his investigations into the origin and nature of isotopes", Soddy received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1921. Aston may have been Soddy's senior by one day, but Soddy beat him to the Nobel Prize by one year.

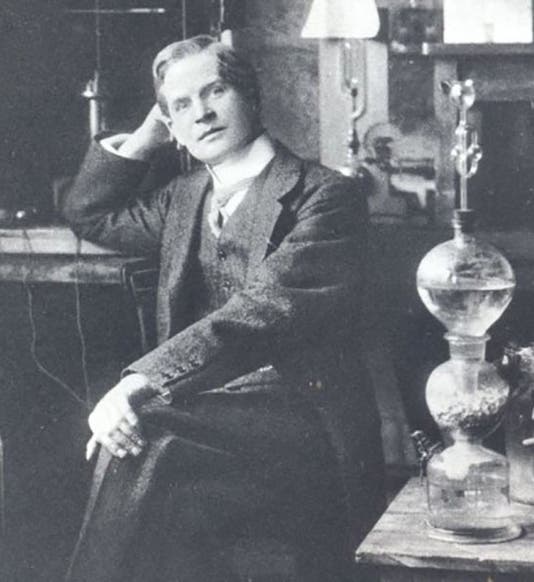

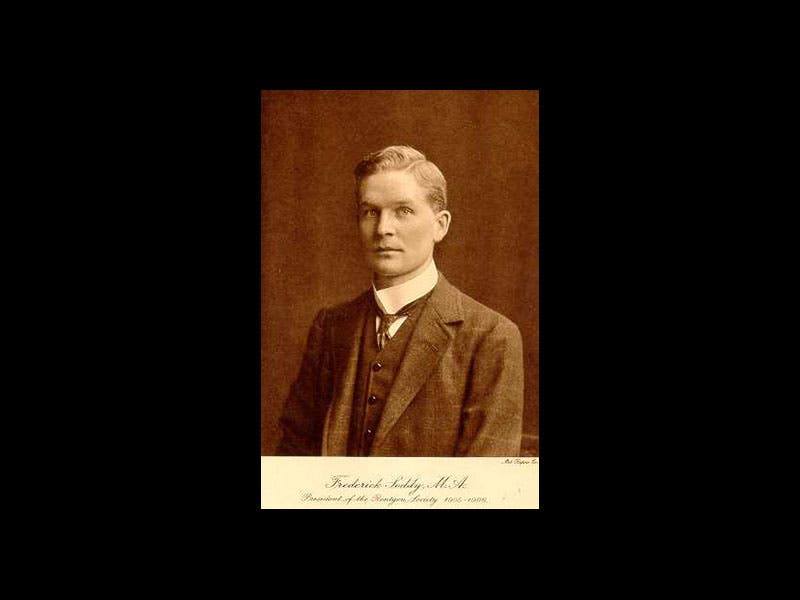

We have two editions of Soddy's Interpretation of Radium in the Library—the first edition of 1909, and a second of 1920. Three images above are taken from the 1909 edition: the title page; a view of the laboratory set-up that allowed Soddy to discover that radioactive decay yields helium gas (third image), and a chart showing the decay of uranium into radium (fourth image). The other images show Soddy at work in the lab at Glasgow, where he had moved in 1904 (first image), and a studio portrait of Soddy when he was at McGill (fifth image).

Dr. William B. Ashworth, Jr., Consultant for the History of Science, Linda Hall Library and Associate Professor, Department of History, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Comments or corrections are welcome; please direct to ashworthw@umkc.edu.